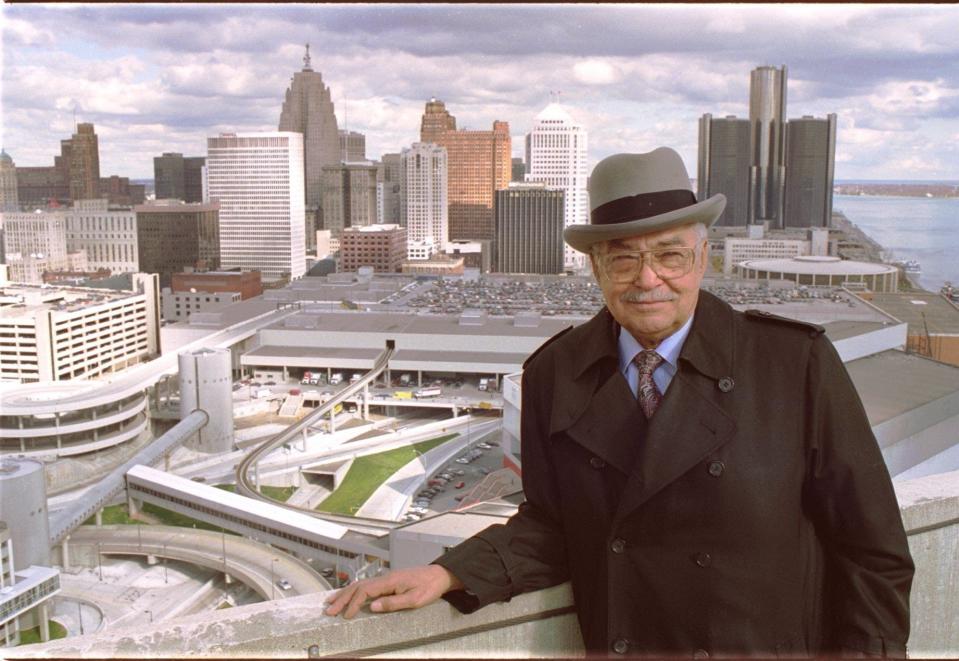

Flashback: What Coleman Young really meant when he said 'Hit 8 Mile' 50 years ago

Detroit ushered in its first Black mayor in January 1974 with a boisterous inauguration that stretched over three days.

Today, the celebration is largely remembered for four much-debated words in Coleman Young’s first mayoral speech that he delivered 50 years ago Tuesday.

“Hit 8 Mile Road!” Young said, addressing criminals in Detroit.

The mayor, who died in 1997, long maintained he was ordering lawbreakers to get out of town. But many suburbanites reacted with anger. They interpreted Young’s words as an invitation for crooks to invade the suburbs.

The controversy has long overshadowed Young’s main message in the speech, an impassioned plea for regional unity. He reached out to all of southeast Michigan, offering an olive branch and requesting Detroiters and suburbanites work together for the good of the metro area. Many white people rejected his offer.

The speech took place during the 72-hour inaugural gala that featured Diana Ross and the Detroit Symphony Orchestra; prayers; praise from CEOs, and a “Soul Train”-style dance line with roughly 1,000 people.

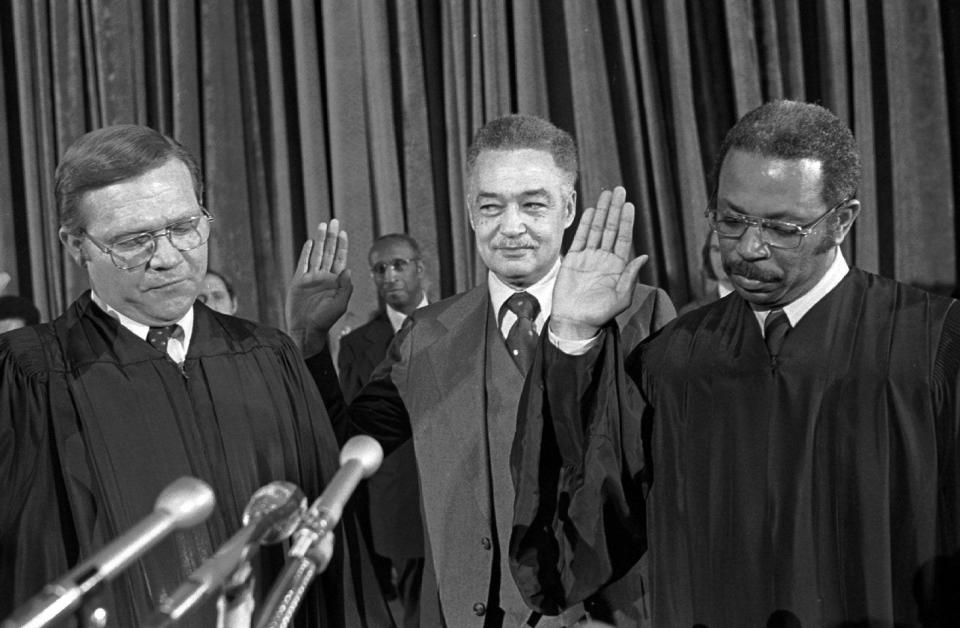

Young spoke at an evening swearing-in at Ford Auditorium. Hours earlier, at a Cobo Hall morning prayer breakfast before 3,000 people, the Rev. Charles Butler introduced Young to the adoring throng by announcing, “Behold the man!”

Butler echoed the words used by Pontius Pilate in presenting Jesus Christ to a jeering crowd before his crucifixion. Pilate’s words are usually interpreted as mockery, but there was no doubt Young was seen as a savior among Black Detroiters.

He threw away the text

While the tenor of the revels for the new mayor was festive and triumphant, the tone of the breakfast speakers turned unusually harsh, mirroring residents’ anger over the city’s struggle with violence. By the end of 1974, Detroit would record 714 homicides, the all-time record, and the “Murder City” nickname would become firmly attached. By inauguration day, Jan. 2, 1974, eight people already had been murdered in Detroit.

U.S. District Judge Damon Keith, a civil libertarian and prominent civil rights leader, reflected the frustration. He called on Young to crack down, to “devise a means of ridding this city, root and branch, of the criminals who are committing murder, rapes and assaults on the people.”

Keith told the breakfast gathering that he understood the “sociological reasons” people break the law, but said Detroit’s crime wave was essentially “sparked by Black criminals preying on Black victims … aided and abetted by Black people” who refuse to cooperate with police.

In the evening inaugural ceremony at Ford Auditorium, Young addressed the crowd after he took the oath of office. His speech was short, just over 500 words. He threw away his text and spoke spontaneously. For most of the speech, he discussed the need for unity among Black and white, city and suburbs, rich and poor, even young and old. He denounced the region’s polarization.

“We can no longer afford the luxury of hatred and racial division,” Young said. “What is good for the Black people of this city is good for the white people of this city. What is good for the rich people in this city is good for the poor people in this city. What is good for those who live in the suburbs is good for those of us who live in the central city.”

Echoing the sentiments of Judge Keith, Young concluded by putting criminals on notice.

It was treacherous ground: he needed to balance citizens’ demands to cut crime with his campaign pledge to integrate and reform the overwhelmingly white police department, long hated as an army of occupation in Black Detroit. Many members of the DPD despised Young, a feeling that was mutual. But Young needed the cops to combat crime.

As the crowd applauded and cheered, Young, his voice rising, launched into his salvo. He said:

“I issue an open warning now, to all dope pushers, to all rip-off artists, to all muggers. It’s time to leave Detroit. Hit 8 Mile Road!”

The crowd of 2,000 stood, interrupting Young with prolonged applause. He continued:

“And I don’t give a damn if they’re Black or white, if they wear superfly suits or blue uniforms with silver badges. Hit the road!”

Calls pour into city hall

To many supporters and others, Young clearly was engaging in the familiar American trope of playing the new sheriff, telling criminals to leave town, using “hit 8 Mile Road” as a figure of speech.

Large swaths of suburbia heard a different message. Many officials and residents took Young at face value. They believed the new mayor had urged “rip-off artists” to raid the suburbs.

In saying “hit 8 Mile Road,” Young evoked the boundary separating Detroit and suburban Oakland and Macomb counties. A half century ago, “8 Mile” didn’t carry the same symbolic weight as it would in later years when the street came to mark the border of a Black city and white suburbs.

Detroit’s population of about 1.3 million in 1974 was still roughly half white, and the neighborhoods closest to 8 Mile were virtually all white. Young’s use of the street name helped transform “8 Mile” into a metaphor for a racial divide.

The speech was big news. The Detroit News reported Young’s audience “howled with delight at his suggestion of chasing the criminals at least figuratively into the suburbs.” The Free Press steered away from the 8-Mile angle but made it clear Young had ordered criminals to leave Detroit.

Complaints about Young’s warning inundated his city hall office. Mayoral aide William Cilluffo insisted the speech was about unity. “We didn’t literally mean we want to push crime over the border,” he pleaded.

Three days after the speech, The News ran a front-page story headlined, “Young’s tough-on-crime remark angers suburbs.”

It reported Young’s statement was taken “literally and seriously” by “hopping mad” officials in several cities bordering 8 Mile.

“He used some very arrogant language in his off-the-cuff remarks and I think he meant it,” said East Detroit Mayor Walter Bezz. “It might have sounded good to the people in Detroit, but it didn’t sound good to the people in the suburbs.”

“Bad taste,” said the Warren City Council president.

“Deplorable,” said an official from Hazel Park.

Other suburban politicians defended the new mayor.

“Coleman Young is too smart to start off his term in office with a deliberate fight with the suburbs,” said Oak Park Mayor David Shepherd.

Waging war on suburbia?

As for Young, he said repeatedly the “hit 8 Mile Road” line was a law-and-order statement and nothing else. “I was just playing Dodge City, telling hoods to get out of town,” he once told the Free Press.

The controversy never went away. However illogical it might have been to believe Young was urging criminals literally to cross 8 Mile Road and raise havoc ― especially in a speech that emphasized regional unity ― many suburbanites have used the line for years as a cudgel to rip Young as a suburbia-hating racist.

Over the decades, some people even have twisted Young’s words to say he had demanded that all white residents of Detroit “hit 8 Mile Road.”

He uttered those four words during his first minutes as mayor. But the cockeyed controversy was a signal of the quarrels to come with suburbanites over his 20 years in office, and the estrangement of the city from its suburbs, which are filled with former Detroiters.

In his 1994 autobiography, “Hard Stuff,” Young wrote: “To this day, a lot of folks in the suburbs believe I’ve been waging war on them since the moment I moved into the mayor’s mansion, if not before.”

He believed that many suburbanites perceived that upon his election as Detroit’s first African American mayor, the city became a Black enclave, that it “split off as a sovereign nation virtually overnight.”

Young added: “I would much prefer that this not be the case.”

Bill McGraw is editor of Free Press Flashback.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Detroit Mayor Coleman Young's 'Hit 8 Mile' comment 50 years old