Florida book-banning: How one former inmate fought the law, and she won

When you think about Florida as "the banned books state," you're probably thinking about schools.

But Florida’s penchant for book banning extends to the state prison system, which bans more reading material for inmates than any other state, even Texas.

In Florida, inmates are banned from reading a diverse set of titles that include The Complete Encyclopedia of Magic, Field and Stream magazine, Popular Mechanics, Betty Crocker’s Good and Easy Cookbook, Tai Chi: Tranquility in Movement, and Reader’s Digest.

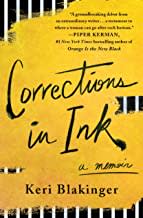

The banned book in Florida that has drawn the most attention lately is Corrections in Ink: A Memoir by Keri Blakinger.

It’s a remarkable book written by an Ivy League English major who landed in New York’s prison system as a result of a heroin addiction and eventually found sobriety and redemption.

As a teenager, Blakinger ice skated six hours a day in a failed quest to be an Olympics figure skater. Trying to make herself more petite for her male skating partners, she taught herself to throw up after every meal.

That led to bulimia and the end of her Olympic dreams. Even with all the skating and an eating disorder, she cruised through high school academically and was accepted as a student at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y.

More: Cerabino: Woke or joke? Trying to feel the pain of straight, white men

More: Cerabino: DeSantis: Proposed state license plate features warning to "out-of-state cars"

More: The Florida Book War of 2023: Trump, DeSantis battle it out for literary supremacy

Her mental health issues got worse there. She survived a bridge-jumping suicide attempt but not the dark spiral of a debilitating heroin addiction. It led to her arrest on a felony drug charge during what would have been her final semester at Cornell.

Prison garb, not a cap and gown

Instead of graduating, Blakinger was sent off to a procession of women’s prisons for about two years. All the while, she kept a detailed journal of her mental and physical journey.

After getting out of prison, she finished her degree at Cornell, and became an award-winning journalist covering criminal justice.

She worked for a time at The Marshall Project, covering prisons issues across the country. She wrote a piece for The Washington Post magazine about the inequities in women's prisons that was selected for the Best American Magazine Writing in 2020.

Writing about what she learned behind bars

And her work at The Houston Chronicle resulted in the Texas prison system being shamed into a new policy that gave dentures to toothless inmates rather than liquifying all their food in blenders.

She recently became a reporter for The Los Angeles Times. In her first story for the newspaper, she went to Mexico and bought pills at pharmacies there that were supposed to be oxycontin and Adderall, but were actually fentanyl and meth.

I read Blakinger’s memoir after reading that the Florida Department of Corrections had impounded the book, because the state prison system's Literature Review Committee found six pages of it objectionable.

They included four pages of Blakinger writing about a fellow inmate trying to fake mental illness by collecting chicken bones and claiming they were her pet chicken. She was not successful.

The other two pages of allegedly objectionable material was Blakinger recounting how a sadistic corrections officer tossed another woman’s cell for hours, reducing her to tears, and then said, “April Fools”, even though it wasn’t April.

A success story deemed too dangerous to tell

The state’s Literature Review Committee decided that those pages were “dangerously inflammatory in that it advocates or encourages” unrest. And that Blakinger’s book “otherwise presents a threat to the security, order or rehabilitative objectives of the correctional system or the safety of any person.”

Blakinger appealed the decision.

“The reasons they gave for banning the book seemed so patently absurd that it made me wonder what the real reasons were," she said.

Her appeal just made things worse. Florida’s six-member review committee tacked more justifications for its previous ban, saying that other passages in the book contained descriptions of “sexual conduct” among the women.

Meanwhile, outside the prison system, Blakinger’s memoir was being hailed as a detailed look at prison life from the inside by a gifted writer and astute observer.

The New York Times called her book “a riveting story about suffering, recovery and redemption. Inspiring and relevant.”

Rather than accepting the judgment of Florida’s book banners, the American Civil Liberties Union, PEN America, and the Prison Book Program wrote letters to Florida’s Corrections Secretary Ricky Dixon, asking him to intervene and reconsider the two rulings banning the book.

“While it honestly describes many problems with current correctional practice and with prison environments, this is not news to the people in your custody,” wrote Kelly Brotzman, the managing director of the Prison Book Program. “There is nothing portrayed in the book that they do not already know.

“If anything, the book makes its readers feel understood,” she continued. “It also depicts a rehabilitative journey from which readers can draw strength and courage.”

The third appeal produces a different result

It worked. Dixon called for the book to be reconsidered, and the ban was rescinded in February.

I'll bet that many authors of books on the banned list couldn't care less about their inmate readership. But Blakinger was ecstatic over the news of Dixon’s action.

"OMG YOU GUYS," she posted on Twitter. "Florida prisons just reversed their decision to ban my book!!!!!!!!"

I asked Blakinger what she would say to Florida's prisons secretary if she got a chance to talk to him.

“I would thank him for setting a good example for the people who are making these decisions on a day to day basis," Blakinger said. "Doing the right thing will send a message to others who make these decisions on a regular basis."

Blakinger promised to send a donated copy of her memoir to 50 of the state's biggest lockups.

"I have the books set aside," she said. "I'm just waiting for an address where to send them."

So, if you're keeping score at home, the book that was deemed too dangerous for any Florida inmate to read will now be made widely available in prisons across the state.

It's a rare, but consequential victory for free speech in the increasingly authoritarian "free state of Florida."

Frank Cerabino is a columnist at The Palm Beach Post, part of the USA TODAY Florida Network. You can reach him at fcerabino@gannett.com. Help support our journalism. Subscribe today.

This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Post: Keri Blakinger's prison book, banned in Florida prisons, gets OK