Florida froze program to help with power bills. Advocates worry it could happen again

It was 91 degrees outside, and the power was off at Nicole Cannon’s home, leaving her three kids sweltering in the heat.

The 38-year-old hotel cook was sweating too, in a long, winding line in the sun at a government building in Pompano Beach. At the other end of the line was assistance: a government program that would help pay her overdue power bill and get the lights — and AC — back on immediately.

“I’m a single mom and still need help,” said Cannon. She was one of hundreds of people hoping for help from a government program running continuously since the 1980s, called the low-income home energy assistance program, or LIHEAP.

Program managers say that the pandemic, along with rising temperatures, have made this entirely federally-funded program invaluable to the more than 175,000 Florida households that depend on it to make ends meet every year.

But despite getting double the funding last year — a cool $170 million statewide — the long-running program ground to a halt earlier this year after the state agency in charge of doling out the cash ran into financial difficulties for reasons that still aren’t clear.

LIHEAP programs around the state shut down for weeks to months, leaving thousands of clients unable to get the help they needed. It also sparked concern from the federal agency that hands out the funds, which visited the state agency for a monitoring visit in August.

Money started flowing again in July, but the state’s Department of Commerce, which runs the program statewide, has still not explained why the mix-up happened, or how it ran out of funds in April after years of record federal funding. The snafu came amid a turbulent few years for the agency, including multiple leadership changes.

In a statement, FloridaCommerce Spokesperson Rose Hebert said the disruption was due to “record demand” and that there was a relatively quick bureaucratic fix.

“In 2022, Floridians across the state experienced difficulties including record inflation, two major hurricanes, wildfires, and tornadoes that caused a record number of families to seek temporary help. Community Action Agencies and FloridaCommerce provided a record amount of funding for these services, and FloridaCommerce worked quickly with the Florida Legislature to secure the additional state budget authority necessary to address the demand,” she wrote.

While federal records show that Florida served about 20,000 more households in 2022 than the year before, so far this year, including the period of delayed funding, applications are down compared to last year.

Advocates worry that without proper safeguards, this could happen again, potentially putting Floridians who depend on this program in a rough spot.

“Hiccups are gonna happen. As a state government, we should really work to do better to ensure that people who depend on programs like this don’t have to negative impacts from the hiccups,” said Zayne Smith, AARP’s Florida director of advocacy. She said the program was “huge” for many of her members, who rely on it to help them afford medications and other growing expenses.

“As a state, we should really be doing better to make sure these programs aren’t falling through the cracks.”

The disruption also had an impact on the people paid to hand out money, staffers at 30 county and nonprofit agencies around the state known as community action agencies. When the April news broke, some were forced to cut staff and slash budgets in response.

“The state put the Community Action Network in an awkward position and required us to figure out how to meet the demand of the residents that we serve and many of us couldn’t. That’s unfortunate,” said Tim Center, chief executive officer of the Capital Area Community Action Agency, the Tallahassee-based agency in charge of distributing funds for this program.

“With good faith, we continue to work with the state hoping that the changes they’re implementing will prevent this from happening again.”

A sweltering line

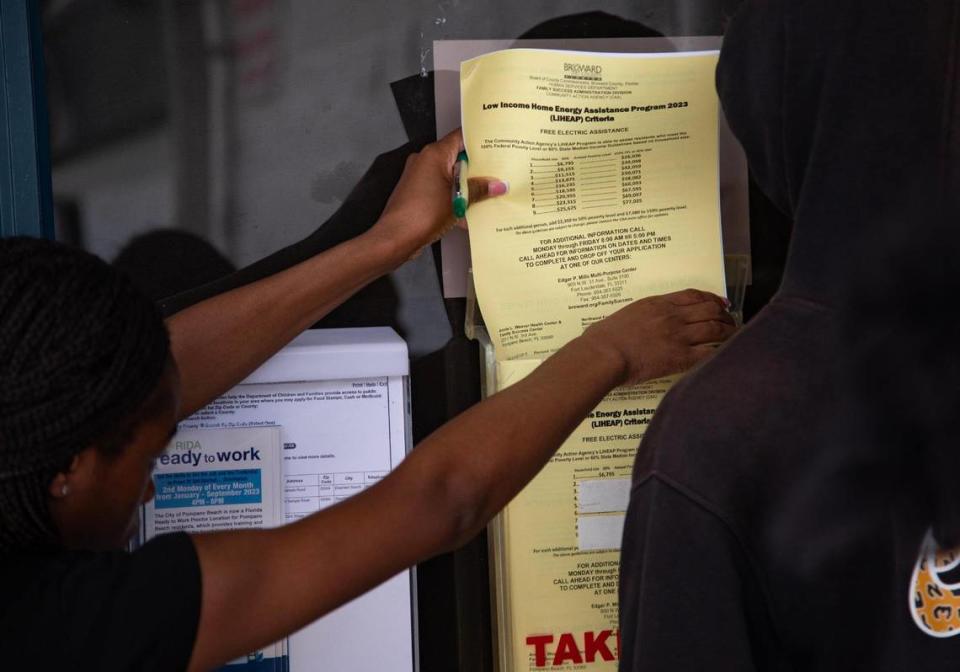

Perhaps one of the best ways to understand how vital this program is to many Floridians was the scene outside a government building in Broward County last month, where a line of people in the sweltering sun wrapped around the building and into the parking lot.

When funding re-starting in July after a three-month break, residents in need of help showed up in droves to apply for funding at the Annie L. Weaver Health Center in Pompano Beach.

Broward County officials said they’d never seen anything like it, and they scrambled to find ways to keep the hundreds of people in line cool while they waited for help. Staffers directed people to wait in their cars, if they had them, and dragged every office chair in the building to any air-conditioned communal space they could find.

Still, the heat was punishing. Paramedics came to the scene to check on at least two people who felt faint in the record-high temperatures baking South Florida.

But for many waiting for help, there was no other choice.

In the shade of a nearby tent erected by Broward County staffers, 65-year-old Lorna Weir sat in her wheelchair, on hold with social security for a piece of information she needed for her application. Weir said her power bill was around $500 a month, thanks to the medically necessary oxygen tank, nebulizer and CPAP machines she uses daily.

She said the program has been “very helpful” in making ends meet, especially with the cost of her medications rising. She said the recent extreme heat has been worsening her illnesses.

“I have to stay inside,” she said.

On that July day, more than 400 people filed applications, which kept a dozen Broward staffers busy for hours, said Natalie Moffitt, director of the county’s family success administration division, which oversees what she said is one of the county’s most popular aid programs.

“We see a spike in the summer months, needs and requests go up this time of year,” she said. “Kids are out of school, it’s hotter and the usage goes up. These are the families who can least afford it.”

And yet, for at least three months this year, they couldn’t get that help.

“I never got a straight answer from [FloridaCommerce] about why,” Moffitt said.

Turmoil and an audit

The recent disruption is the most visible problem with a program that has, by the state’s account, grown in popularity over recent years.

And while the last three years have seen record federal funding for Florida’s energy assistance program, they’ve also been accompanied by a period of record turmoil for the agency in charge of delivering that cash to the people who need it.

The Department of Economic Opportunity, now called FloridaCommerce, faced intense scrutiny in 2020 over its unemployment system, a lifeline for many Floridians suddenly out of work in the early pandemic.

Since then, the department had had four different leaders, the most recent of which, Alex Kelly, deputy chief of staff to Gov. Ron DeSantis, was tapped to lead the department in May. But earlier this month, Kelly was named the governor’s new acting chief of staff, leaving the newly named department without a permanent head once again.

Multiple staffers, including some who managed the LIHEAP program for years, have also left the department in this window.

With fewer staffers, the department has also been granted much higher— at times double — funding for the energy program. And yet, in April, the department had to make an emergency budget request to the Florida legislature. The program didn’t run out of cash, it ran out of permission to spend its cash, something the legislature controls.

While the legislature quickly granted that request, the department was unable to reimburse any of the community action agencies until funding restarted in July. That wasn’t fast enough for some of the agencies across the state charged with handing out the funding.

Broward County laid off 14 temporary staff the same day the department notified them of the budget issue. Only four have been hired back. By the time the funding came back online in July, Moffitt said they were forced to turn away a little over 1,000 people looking for help.

Miami-Dade County also turned away nearly 500 hundred people, but both counties were able to send about 600 people to an alternate program run by Florida Power & Light.

In Tallahassee, Center’s agency limited the help it offered to only the most dire of cases — the elderly, the disabled and those with young kids at home.

The disruption also piqued the interest of the federal agency that hands out the cash every year, the Department of Health and Human Services. Department officials met with the state, as well as multiple community action agencies, in early August to quiz them about how funding works in Florida.

HHS did not agree to an interview with the Herald, but in a statement, said the August audit was a “standard monitoring visit” to “ensure all federal requirements are being met.”

“HHS is dedicated to ensuring that congressionally appropriated funds are adequately and appropriately distributed to their intended recipients, according to any and all applicable federal statutes and regulations. HHS is working closely with the Florida Department of Economic Opportunity (DEO) and continues to provide extensive training and technical assistance to help the state meet its obligations,” the statement read.