Florida judge's COVID mask ruling sidesteps words of former Supreme Court justice | Frank Cerabino

The ruling of a federal court judge in Florida to invalidate the mask requirement for commercial airline, train and bus passengers this past week reminded me of a discussion I had four years ago with then-retired U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens.

Stevens, who lived in Broward County and died a year later at the age of 99, was appointed in 1975 by President Gerald Ford to the nation’s highest court. In his 35 years there, Stevens left behind a legacy of consequential decisions, including a legal doctrine known as “the Chevron deference.”

Did they do the math? Banning CRT from Florida math textbooks is my pi in the sky agenda | Frank Cerabino

Thank you, Grandma! New law offers incentive for out-of-state teens to be nice to Florida grandparents | Frank Cerabino

This is democracy? 'Fairness' in redistricting congressional seats made a mockery in Florida | Frank Cerabino

It refers to a 1984 U.S. Supreme Court opinion written by Stevens that directed courts to defer to interpretations of laws made by the governmental regulatory agencies that are empowered to enforce them, unless those interpretations are unreasonable.

Making rules for questioning gov't agency rules

The case of Chevron USA v. Natural Resources Defense Council had to do with the Environmental Protection Agency’s interpretation of the Clean Air Act of 1963.

But its scope went far beyond that. The case established the proposition that lawmakers can’t anticipate every possible interpretation of the laws they pass, and so when there’s a question of interpretation, courts should give deference to the interpretation of the government agency empowered with enforcing the law.

When I spoke with Stevens, he was especially proud of the effect his Chevron deference opinion had in guiding a generation of court decisions.

“It’s been cited 15,900 times,” he told me. “But it’s now being subjected to criticism that’s incorrect.”

For that reason, I’m guessing that Stevens would have taken issue with the ruling of U.S. District Judge Katherine Kimball Mizelle in striking down the public transportation mask mandate. I’ll bet Stevens would have called it “incorrect.”

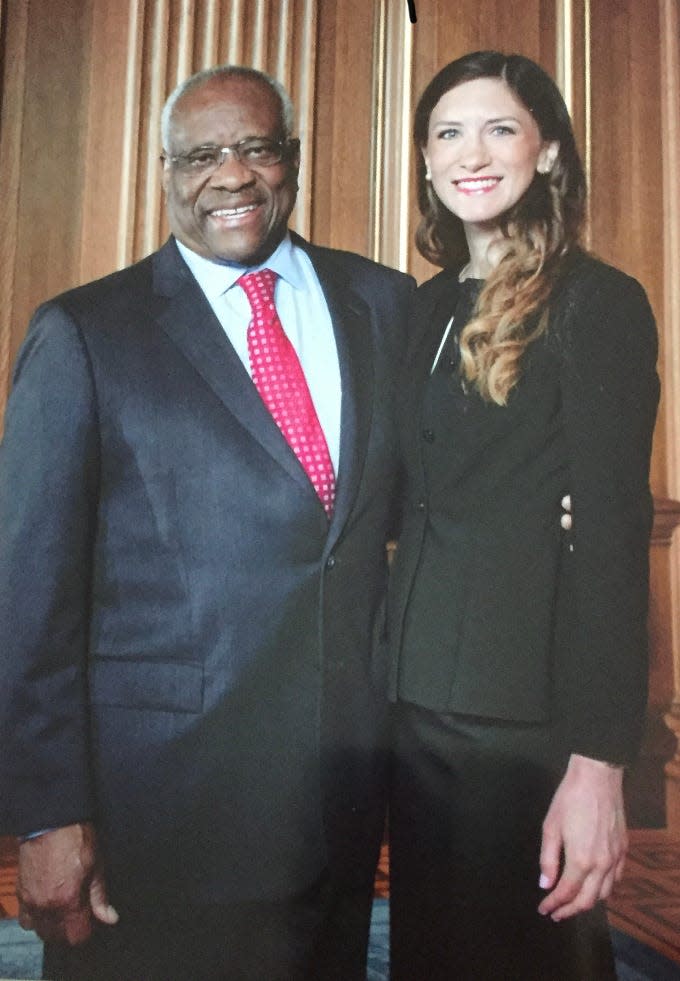

A lot has already been written about Mizelle, a former law clerk to U.S. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, who was appointed as a U.S. district judge in the lame-duck days of the Trump Administration.

And how, at 33, with only eight years as a lawyer and no trial experience, she got a lifetime appointment to the federal bench while being rated “not qualified” by the American Bar Association.

But what is more meaningful here is the legal reasoning that Mizelle used to justify overriding the federal Centers for Disease Control’s ability to enforce a public health measure during the COVID-19 pandemic.

One federal judge v. gigantic federal agency

Whether you agree with Mizelle’s ruling or not, you have to admit that it puts the scientific judgment of one inexperienced non-scientist judge against a government agency with 21,000 full-time employees that include some of the nation’s most qualified medical experts, who do research and guide public health policy with an annual budget of more than $10 billion.

The government’s lawyers had invoked the Chevron deference in this case, saying that the court was compelled to yield to the CDC’s interpretation of the public health law when it came to establishing rules for masks in public transportation.

But Mizelle cast it aside.

“A court may not rest on Chevron to avoid rigorous statutory analysis,” she wrote.

She found that the case hinged on a narrow interpretation of the word “sanitation,” finding that masks can’t be viewed as sanitation, as the CDC had done.

“Wearing a mask cleans nothing,” she wrote. “At most, it traps virus droplets. But it neither ‘sanitizes’ the person wearing the mask nor ‘sanitizes’ the conveyances.”

Her ruling dovetails with a larger effort of groups that have a vested interest in stripping government enforcement of laws that affect their business practices.

Critics of the Chevron deference want to keep the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives from regulating guns. They want to keep polluters from being regulated by the Environmental Protection Agency. They want to keep the Federal Communications Commission from regulating radio, TV and internet companies.

And in this case, they want to stop public-health agencies from making public-health decisions.

In 2017, Republicans in both houses of the U.S. Congress tried to pass a law to repeal the Chevron deference, but it didn’t pass. But the work to erode Stevens’ landmark opinion continues, as evidenced by this ruling. So this seems like as good a time as any to consider Stevens' words on the subject.

Here’s a passage from Stevens’ opinion, one that seems as on point today as it was when he wrote it 38 years ago:

“Judges are not experts in the field, and are not part of either political branch of the Government. Courts must, in some cases, reconcile competing political interests, but not on the basis of the judges’ personal policy preferences.

“In contrast, an agency to which Congress has delegated policy-making responsibilities may, within the limits of that delegation, properly rely upon the incumbent administration’s views of wise policy to inform its judgments.

“While agencies are not directly accountable to the people, the Chief Executive is, and it is entirely appropriate for this political branch of the Government to make such policy choices — resolving the competing interests which Congress itself either inadvertently did not resolve, or intentionally left to be resolved by the agency charged with the administration of the statute in light of everyday realities.

“When a challenge to an agency construction of a statutory provision, fairly conceptualized, really centers on the wisdom of the agency’s policy, rather than whether it is a reasonable choice within a gap left open by Congress, the challenge must fail.

“In such a case, federal judges — who have no constituency — have a duty to respect legitimate policy choices made by those who do. The responsibilities for assessing the wisdom of such policy choices and resolving the struggle between competing views of the public interest are not judicial ones.”

If there was any doubt about the political nature of Judge Mizelle's mask ruling, it was extinguished within minutes, when Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis took a victory lap on Twitter.

"Great to see a federal judge in Florida follow the law and reject the Biden transportation mask mandate," DeSantis tweeted.

Follow the law? More like "make the law." I'm old enough to remember when Republicans were the ones sounding the alarm about "activist judges."

So, on behalf of another judge who resided in Florida — one who was eminently qualified and had spent as many years on the U.S. Supreme Court as Mizelle has been alive — I'd like to register his posthumous dissent.

fcerabino@gannett.com

@FranklyFlorida

This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Post: COVID mask ruling conflicts with opinion that guided courts through years