Florida juvenile justice’s long history of scandals

For decades, the Florida Department of Juvenile Justice has been beset by periodic scandals. Here is a recount of some of them:

2000

The confrontation between Michael Wiltsie at a Central Florida wilderness camp was a mismatch: 12-year-old Michael was a willow of a youth, weighing 66 pounds. The worker who restrained him weighed in at 300.

Michael had been incarcerated at Camp E-Kel-Etu in Marion County. He was small in stature, and he suffered from mental illness. His mother, Linda Ibarra, claimed in a lawsuit that the camp’s staff cut Michael “cold turkey” from his psychiatric medication and offered the boy no treatment services for his diagnosed bipolar disorder — and the behavioral problems that resulted from it.

On Feb. 5, 2000, a much larger counselor placed all of his weight on Michael during what was described as a “full-body restraint.” Michael “kept yelling that he could not breathe,” a death review said, though the staffer refused to get off the boy. The counselor told authorities “he believed the child was playing possum.”

Michael’s death spurred several investigations, though ultimately no one was held to account; the Department of Children & Families concluded it could find no evidence the counselor acted “with utter disregard for Michael’s safety.” Six years after her son’s death, Ibarra took her own life, leaving behind a 7-year-old son.

“She was so broken,” Ibarra’s lawyer told the Miami Herald.

Later in 2000, 15-year-old Anthony Dumas hanged himself with a black woven belt at the Lippman Youth Shelter in Oakland Park. Three youth workers on duty that night left him hanging.

In a memo, a prosecutor wrote it was “extremely neglectful for [one of the workers] to fail to act in any fashion to relieve the pressure on his neck regardless of whether she truly believed that he may have already died.”

Anthony had been placed at the shelter in response to what his parents called escalating defiant behavior. He had given warning signs that he’d become suicidal, but shelter workers ignored them.

On the night of Oct. 14, 2000, Anthony was found hanging from his bunk bed, tethered to his belt. Workers left him there, and took Polaroid instant camera pictures of the scene — for liability purposes, they later said. The three youth workers were ordered fired by the Department of Juvenile Justice. The employee who took pictures later was convicted of child neglect and served a year under house arrest.

2003

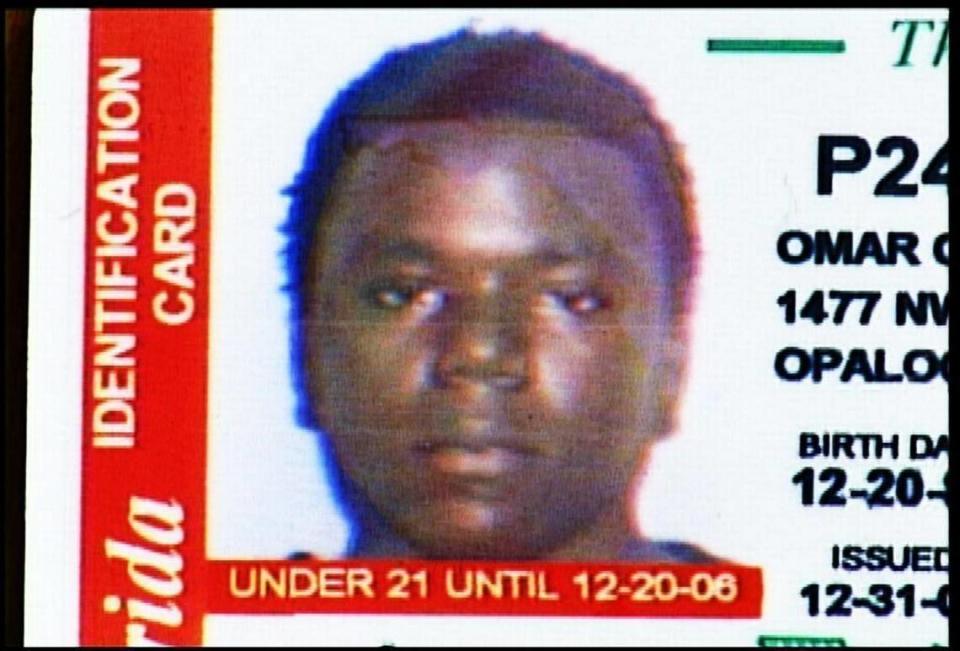

Omar Paisley was awaiting sentencing at the Miami-Dade Juvenile Detention Center on charges he brandished a broken soda can during a fight. His stay at the long-troubled facility became a death sentence.

For three days, Omar complained to nurses and detention workers that he was in agony. But both the health workers and guards dismissed his complaints as malingering. On June 9, 2003, Omar died from a ruptured appendix — which had been filling his belly with poisons — just as guards were handcuffing him for a trip to the hospital.

Detailed in a series of Miami Herald reports, Omar’s death outraged Florida lawmakers — two Miami-Dade legislators in particular, one a Republican, the other a Democrat. Then-Rep. Gustavo “Gus” Barreiro, a Miami Beach Republican, chaired a series of hearings into the boy’s death, and current Miami Beach Mayor Dan Gelber, then a House Democrat, also called for far-reaching reforms.

Omar’s excruciating death became a symbol of what lawmakers called “a culture of neglect” at the state’s juvenile justice agency. Within a year, DJJ Secretary William “Bill” Bankhead, two of his deputies, the lockup superintendent and about 20 other DJJ employees all had been fired or had resigned. Two nurses were charged with third-degree murder; one pleaded guilty to culpable negligence and was sentenced to probation. Prosecutors dropped charges against the other.

“Animals are treated better,” said the forewoman of a grand jury that released a damning report on Omar’s death.

2006

Martin Lee Anderson was sent to the Bay County Boot Camp for the crime of joyriding in his grandmother’s Jeep.

On the day he arrived, 14-year-old Martin was ordered to run laps around a track — a kind of initiation ritual at the military-style camp. He told drill instructors he couldn’t complete the course. The guards accused him of faking a medical condition and punished him with a violent takedown that lasted almost a half hour — with punches to his arms, knee jabs and a dose of ammonia tablets in his nose that authorities later said led to his inability to breathe.

The episode was captured on video. The Miami Herald, along with CNN, sued for the recording’s release, and the footage shocked viewers when it appeared again and again on television.

The boy’s death, combined with the emotional public reaction to the video of eight men manhandling the boy, brought speedy and significant changes. Then-Bay County Sheriff Frank McKeithen, who ran the boot camp, shuttered his program, saying the intense scrutiny of his camp had made it impossible to operate.

And, later, Florida Department of Law Enforcement Commissioner Guy Tunnell resigned, several days after The Miami Herald reported he had written several friendly emails to McKeithen even as his agency was investigating McKeithen’s boot camp.

In a bill lawmakers named after Martin, the Legislature banned juvenile military-style boot camps that used physical violence and so-called “pain compliance” techniques to force discipline. Seven guards — as well as a nurse who stood by passively while Martin was manhandled — were charged in Bay County with manslaughter. All were acquitted.

2008

Outrage over the Arthur G. Dozier School for Boys had been brewing ever since the school’s opening in January of 1900. But the Panhandle reform school could not survive the shock that ensued when a group of former inmates disclosed what had happened to them while incarcerated there in the 1950s and 1960s.

They called themselves “the White House Boys” in recognition of what happened to them inside a squat, white-washed cinder-block cottage on the Marianna prison’s wooded campus. In October 2008, the Herald disclosed that hundreds, if not thousands, of children had been beaten bloody, sometimes scores of times, with a long leather barber-style strap that was made partly of sheet metal. Other former inmates, many now in their 60s and 70s, said they were taken to what they called “the rape room” to be brutalized by guards.

A hidden cemetery was discovered on the Jackson County campus.

In 2011, the U.S. Justice Department released a scathing 28-page report on Dozier and a nearby facility asserting that children were assaulted by officers, denied necessary medical care and punished harshly for minor infractions. Justice Department investigators found that many of the abuses at Dozier — and Florida’s juvenile justice system as a whole — stemmed from “a systemic lack of training, supervision and oversight.”

Though DJJ administrators and Dozier superintendents had come and gone, the prosecutors wrote, conditions at the prison remained so harsh as to violate the Constitution’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment.

DJJ shuttered the reform school in June of that year.

2011

Once again, juvenile justice workers confronted a critically ill youth and accused him of feigning injuries.

Eric Perez was arrested after police noticed a broken tail light on his bicycle and stopped him, finding a small amount of marijuana. He turned 18 at the Palm Beach County Juvenile Detention Center. It was his last birthday.

Though such “horseplay” by guards is forbidden, a detention officer dropped Perez on his head while goofing around with the teen. In the ensuing hours, Perez vomited, hallucinated and complained of severe head pain. A nurse, called repeatedly for advice, never responded.

Once again, video footage captured a youth’s final hours. It depicted guards dragging Perez’s limp body on a mat from his cell to a common area where he could be observed continuously, and back again. Authorities said this demonstrated workers suspected something was wrong with the youth. Nevertheless, lockup supervisors failed to seek medical attention until it was too late.

In March of the next year, a West Palm Beach grand jury declared “fundamentally and woefully inadequate” the medical care Perez received when lockup staff ignored for hours his deteriorating condition.

“The only attempt to seek an outside medical opinion during the entire episode was two phone calls to the head nurse that went unanswered during the night,” said the grand jury report.

The presentment added: “More effort was spent cleaning the floor around the youth than attending to his welfare.”

Six lockup employees were fired as a consequence of Perez’s death.

2015

They called the practice “honey-bunning” after the gooey confection often sold in prison and detention center vending machines. But there was nothing sweet about how guards at the Miami-Dade Juvenile Detention Center used the treats.

Miami prosecutors later claimed that the practice of deploying teenage detainees as lockup goons and enforcers had been long-standing, and Miami Herald reporting showed it was not confined to Miami.

For years, youth workers used hamburgers, candy, vending machine desserts, and even sneakers as rewards to youths willing to mete out punishment against other youths guards considered defiant or unruly. In the parlance of Florida juvenile justice, the victims of such attacks were said to have been “honey-bunned.”

In August of 2015, a honey-bunning at the long-troubled Miami lockup turned fatal.

Seventeen-year-old Elord Revolte, who had briefly been in foster care after being left alone at the Miami airport, provoked the ire of a detention worker when he left his cafeteria seat without permission for a carton of milk — and then mouthed off when reprimanded. Records and court testimony showed the officer ordered other youths to attack Elord, who was then beset by more than a dozen detainees who kicked and punched him before officers could react.

Elord died at Jackson Memorial Hospital on Aug. 31, 2015, after a vein beneath his left collarbone slowly oozed blood until he stopped breathing.

Five lockup staffers, including three supervisors, were fired for infractions that included failing to oversee detained children and falsifying official reports.

In spring of 2018, a federal grand jury in Miami indicted the officer accused of orchestrating the attack on Elord, saying he and other officers “operated a bounty system in order to help ensure obedience and officer respect.”

“By and through this bounty system,” an indictment alleged, the guard “caused, encouraged and induced juvenile detainees, in exchange for rewards and privileges, to forcibly assault” Elord.

The officer later was found not guilty after a trial.