Florida Shuffle: State's failure to oversee addiction treatment leaves patients in deadly danger

RIVIERA BEACH – Joseph Havrilla’s body lay hidden by palmetto bushes in front of a Publix for four months before it was found.

Long before he went missing in late September 2022, the 25-year-old from Maryland already had been lost in a labyrinth of addiction treatment, relapse and return to treatment that is so identified with state regulatory failures it is nationally known as “the Florida Shuffle.”

Havrilla’s disappearance was the final step of an odyssey that had begun a year earlier.

The Florida Shuffle starts when unqualified providers lure patients to the state, marketing addiction treatment that has met no medical standard. It feeds a corrupt economy that makes failed treatment more profitable than recovery. Raising the odds of patients slipping back into substance use, the Florida Shuffle feeds a toll of overdose deaths that is among the highest in the nation.

It is a cycle enabled by the inaction and incompetence of Florida’s Department of Children and Families, the agency that is supposed to oversee private addiction treatment, a Palm Beach Post investigation has found.

DCF is responsible for regulating an industry notorious for fraud, negligence and abuse but provides no oversight with its monitoring systems in disarray to the point of dysfunction. With no medically qualified staff to evaluate the programs it licenses, DCF leaves patients struggling to overcome addictions on their own.

The agency:

Does not hold facilities to evidence-based standards of treatment or take steps to ensure patient safety;

Is unable to quickly locate information needed to respond to violations and so cannot hold addiction treatment providers accountable for harmful practices;

Ignores or remains unaware of repeated violations and relies on facilities to correct their own lapses.

DCF Secretary Shevaun Harris did not respond to questions from The Post for this report.

Defining the disease: Why do some people get addicted and some don't? It's not the drugs; it's the disease

The agency's inability to regulate the industry opens the largest addiction treatment field in the nation to operators with no expertise in medicine, addiction or psychiatry.

Countless out-of-state patients who come here to recover go untreated as a result.

A rising toll of fatal drug overdoses over the past decade led the Palm Beach County State Attorney’s Office in 2016 to form its sober home task force, now known as its addiction recovery task force, the first in a series of groundbreaking efforts here to tackle abuses in addiction treatment. The county Health Care District also established a pioneering hospital unit to link overdose patients to immediate help.

In the years since, with input from the task force, Florida legislators across party lines have passed laws governing the treatment industry and strengthening DCF’s authority over it. The laws have been recognized as the most comprehensive in the nation.

More: Is 'tranq,' the 'zombie drug' that can cause amputations in Palm Beach County?

As DCF issues and renews licenses to drug treatment centers without overseeing their safety or quality, however, drug overdoses kill thousands of people, who, like Havrilla, came to the state in hopes of conquering their addictions.

Across Florida, the toll continues to rise. Palm Beach County, where a drop in the number of licensed addiction treatment programs followed task force investigations, has seen a decline in overdose deaths but still, drugs killed 553 people here in 2022.

Drug crimes and nonfatal overdoses overwhelm local first responders.

Police departments cited staff shortages in the past year as they withdrew officers from the task force’s investigative arm.

Fire rescue responders bypass the new addiction treatment trauma center and take patients instead to the nearest emergency rooms.

A growing population of endangered people lost in the Florida Shuffle disappears, unsought and unfound.

Havrilla’s skeletal remains were discovered a block from where he was last reported seen.

More: How a parent’s burden never ends with the disease of addiction

That last day, Havrilla overdosed on fentanyl and was revived by paramedics. Narcan had reversed the effects of the drug but had thrown him into immediate symptoms of withdrawal. He was desperate.

He called a detox facility, his mother and his girlfriend, seeking a way back to treatment.

He was crying the last time he talked to his mother. He wanted to get well.

He spent the day seeking help and drugs.

He found the drugs first.

More: 'They are making a killing, literally': How an evolving drug trade ends in more deaths

Chapter 1: 'Sobriety doesn't pay'

About nine months before he died, Havrilla came to Delray Beach for treatment in a series of steps from detoxification and inpatient treatment to outpatient treatment.

He would spend most of his time as an outpatient.

That outpatient model has brought patients to South Florida’s beachfront towns and cities for decades. With medically overseen, evidence-based treatment, the model allows patients to rebuild their lives in supportive communities of others in recovery.

When provided by businesses without expertise, the model opens opportunities for patients to slip back into substance use while the spread of fentanyl raises the odds they'll die.

In the past decade, two federal laws unintendedly spurred operators without medical expertise to join the profitable field of addiction treatment. The Affordable Care Act allowed young adults up to age 26 to remain on their parents’ insurance, and the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act required insurance providers to cover addiction care.

While expanding access to addiction treatment to people who need it, the laws also opened lucrative opportunities to exploit vulnerable patients far from home, making medical oversight by a qualified regulatory agency more critical than ever.

Laboratories can bill insurance for redundant rounds of expensive drug tests and bribe treatment centers to send the tests to them. Exploitive operators advertising resort-like amenities compete with providers that offer effective therapies.

People with addictions lose their value when they reach recovery, Chief Deputy State Attorney and task force leader Al Johnson notes: “Sobriety doesn’t pay.”

Returns to treatment and regular drug testing, on the other hand, provide reliable sources of revenue.

Florida, one of only a handful of states to assign regulation of addiction treatment to an agency with no expertise in health care, provides no guidance to help prospective patients navigate this landscape.

People looking for an assisted living facility, an abortion clinic, a home health agency or 30 other medical services in Florida can search listings on the state’s Agency for Health Care Administration website for inspection reports, complaints and violations.

DCF's limited use of digital technology hampers the agency in locating the most basic information on addiction treatment programs it oversees and compromises its abilities to either enforce regulations or provide help to the public.

The DCF website includes a portal for providers to upload licensing documents and for consumers to register complaints. Not all relevant documents are there, however, DCF’s Deputy General Counsel John Jackson said.

In response to a Post public records request, DCF Deputy Chief of Staff Mallory McManus estimated three days of staff time would be needed to find records on two of the centers Havrilla checked into.

Three days turned out to be a grossly low estimate. DCF provided The Post incomplete records on one of the centers after five weeks, and after another request, took four weeks to provide additional and still incomplete records.

The delay as well as the projected fee of $700 for the records would stand as obstacles to patients seeking to vet a provider. A list of complaints provided about addiction treatment programs across the region that includes Palm Beach County didn’t identify them.

The documents included a page saying the system had no data for 2022, the year Havrilla came to Florida and died.

Sober home doctor convicted: Prosecutors fight Mark Agresti's bid for a new trial, say witness didn't lie to jurors

Chapter 2: 'No one would choose to suffer like this'

When Havrilla, whom his family called J.C. and friends called Jay, was not in the grip of chaotic drug use, he was kind and funny. He kept close relationships and earned a full academic scholarship to Rollins College in Winter Park before falling back into drug use.

Amanda Davidson met him when he was sober at a Delray Beach treatment program in February 2022.

“His smile took up his whole face,” she said. “If you were on the receiving end of one of his winks, you felt like you were the only person in the world.”

His addiction had led to repeated arrests. Multiple overdoses had taught him to stay near people when he used drugs so he could be saved. He hadn’t been free of drug use for more than a few months at a time since his teens.

At 32, Davidson’s life also had been overtaken by addiction, recovery and return to use over the preceding decade. Treatment in Florida about a dozen years earlier had helped her. She had gone on to earn her bachelor’s in English literature and a master’s in public administration.

In February 2022, she returned to Florida for treatment.

She is insightful when she describes the critical role of intensive therapy to treat addiction as well as for the traumatic experiences that accompany it. She is candid about her own recklessness.

She and Havrilla left treatment facilities against medical advice, slept outside and overdosed repeatedly. On one day, she found herself in the same emergency room twice.

“I’m tired of bringing you back,” the nurse told her.

Davidson can understand why.

But she doesn’t understand people who believe addiction is a moral failing.

“I don't profess to know the science behind addiction,” Davidson said, “but I do know that if given the choice, no one would choose to suffer from this.”

Dr. Robert Moran, a psychiatrist, certified addiction specialist and member of the task force, does know the science. He has pressed DCF to require that medical directors of treatment programs have relevant credentials with specialties in psychiatry and addiction medicine.

He founded and runs the Family Center for Recovery in Lantana.

Not everyone exposed to a substance ends up addicted to it, he explains. Only about 9% of adults who use cannabis on a regular basis, for example, go on to develop addiction. About 45% of people using opioids will develop addiction. That still is not the majority of people exposed, he notes. A genetic predisposition to addiction or early severe trauma makes the difference between becoming addicted or not.

“Like so many other medical illnesses,” he says, “one has to have the risk factors that then put them on that pathway to develop the disease, if and only if he gets exposed to the substance.”

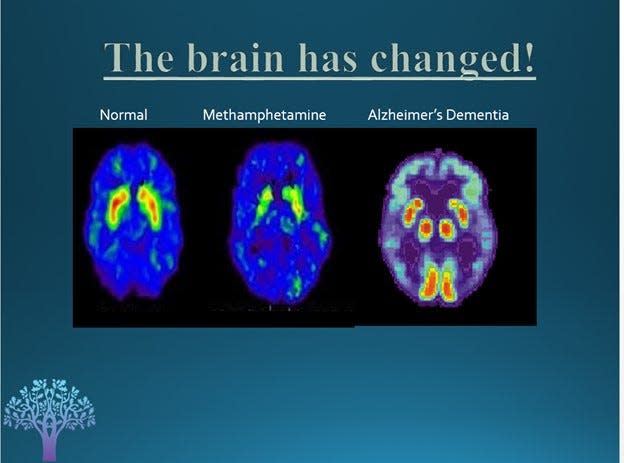

Neurological imaging shows brain circuits governing behavior stop working in people with severe and active substance use disorders, resulting in anti-social and self-destructive behavior.

Imaging also can show patients’ brain function when they were admitted to treatment as well as changes 15 days later and 30 days later.

“I have one that shows someone who’s been using cocaine on a regular basis prior to treatment, and 30 days later, that brain has not normalized,” he says. “Yet how typical is it for that person to be discharged from treatment out into the community? With an abnormal brain! So how can you not expect relapse?”

Regaining control of cognitive functions that include planning and impulse control can require medication that blunts cravings for drugs.

At least half of people with addictions also need medication that must be monitored for mental illnesses, including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia and post-traumatic stress disorder, Moran said.

Expertise in the science of addiction and illnesses that can accompany the disease is critical to evaluating addiction treatment protocols, he said.

As of last year, DCF had never had a single staff member who was medically qualified to evaluate the addiction treatment provided by the programs that the department licenses, Moran notes.

“How silly is that?”

DCF did not respond to a question about the qualifications of its current addiction treatment licensing and monitoring staff.

Chapter 3: 'Inexperience caused a lot of unnecessary headaches'

In 2016, more than a dozen police reports of incidents that included multiple drug overdoses, burglaries, assaults, a stabbing and sexual battery at a single house drew task force investigators’ attention.

The house was one of several sober homes owned by real estate investor Jayeshkumar Dave, who also owned an outpatient addiction treatment facility in West Palm Beach, to which patients at his sober homes traveled.

In sworn statements to police, three former patients and residents of Dave’s homes described unsafe conditions where drug use was open, medicines were unaccounted for and at one, where a gun was left out and a garage with mattresses on the floor was used as a dormitory. Outings for residents provided by house managers included an excursion to a bar in Fort Lauderdale, one said.

The three also said they were offered money to recruit patients and were given cigarettes and gift cards to attend treatment sessions. A police search of Dave’s Facebook messages yielded “countless pages” documenting travel for prospective patients arranged by him.

Investigators arrested Dave on felony patient brokering charges in May 2017.

Dave’s attorney argued that the cigarettes and gift cards had been provided to reward attendance and participation, not to bring people to the facility.

By March 2018, after two of the witnesses had left the state, prosecutors dropped the charges.

Dave says now that his personal contact with patients made him the focus of resentment over rules, disciplinary actions and evictions, leading patients to lie to investigators.

“Patients complain that no one knows their name,” Dave said. “I decided to be hands-on. I think that was my mistake. Inexperience caused a lot of unnecessary headaches.”

For his next endeavor, he decided to leave operations to the staff. Dave applied for a license to open Aloha Detox Center, a residential inpatient treatment facility in western Delray Beach in December 2020.

“I know you are going to ask why DCF gave another license to someone like me, who had been investigated,” Dave said recently.

A short answer is he wasn’t convicted of a felony.

But the information DCF's staff had as they decided to license Aloha remains unclear.

Required documents to attain a license are lost in the department’s files. The missing documents include service contracts, health and food inspections and patient referral logs that DCF did not provide in response to The Post’s public records requests.

A license application for Aloha that DCF did find included the program’s answer to the question of the number and length of weekly counseling sessions and length of stay.

Aloha responded that treatment would be “conducted on a regularly scheduled basis” with its content and schedule “the responsibility of the program coordinator.”

In contrast, Dr. Moran’s Family Center for Recovery describes residential treatment including at least one hour-long individual and family therapy and 14 hours of group therapy in a week with an average duration of seven to 10 days.

Aloha’s response was good enough for DCF.

Aloha is in a secluded cul-de-sac at the end of a medical office plaza surrounded by a quiet residential neighborhood. Since 2021, Delray Beach police and paramedics have been called there close to 200 times with reports of drug use, mental health crises, fights and complaints about staff.

In 2022, it became a repeated stop on Havrilla’s and Davidson’s Florida Shuffle.

Chapter 4: 'We had a job to do ... turn our lives around'

A relationship formed during addiction treatment can feel like a lifeline, Davidson said.

“We had a job to do, which was essentially to turn our lives around,” she said.

Havrilla took recovery seriously, she said, but made life fun again.

He loved to dance and didn’t care what he looked like.

In a Starbucks, he would invariably look around with a show of being impressed and ask the barista if they had considered opening other locations.

Alone with Davidson, Havrilla would make her look in the mirror and tell her reflection that she loved her.

After a little more than three months he was discharged from treatment, and Davidson was out the next week. They lived separately but saw each other daily. Recovery takes years. When he slipped, so did she. In about a month, both had relapsed.

Boynton Beach police, summoned to a motel in June 2022 by a report of an overdose, found Havrilla half-conscious on a bench outside. When he refused to come with them to a hospital, they issued him a notice to appear in court on a charge of resisting arrest and took him to Delray Medical Center.

Five days later, Palm Beach Gardens police saw Davidson’s car in a drug store parking lot, broken glass from the driver side window next to it. Davidson was in the passenger seat, and Havrilla lay across her lap. When he refused to get out of the car, police used a Taser. They took him to Gardens Medical Center because of the Taser use and then to the Palm Beach County jail on a charge of resisting arrest.

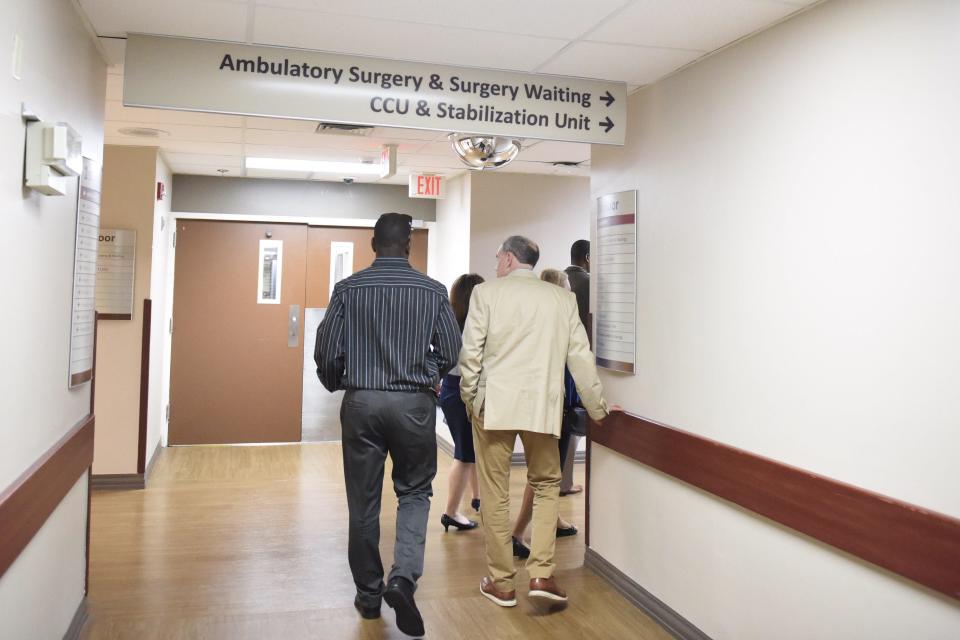

On neither occasion did police or paramedics take Havrilla to the Addiction Stabilization Unit, billed as “an ER for overdose victims,” a place that had been created to interrupt the cycle into which Havrilla and Davidson were falling.

The unit offers on-the-spot access to Suboxone, a medication that blocks withdrawal symptoms and craving for opioids. A peer counselor offers direct and immediate links to whatever care the patient needs next, from detox to treatment to support groups. More than 60% of patients with opioids in their system accepted the Suboxone, greatly reducing their chances of overdosing again. The majority also proceeded to some form of treatment.

At the facility’s launch two years before Havrilla’s arrival here, fire rescue departments across the county had pledged to prioritize bringing overdose patients directly to the unit at JFK North Medical Center in West Palm Beach.

About 30 minutes from where Boynton Beach police took Havrilla for his overdose, the trip would have taken responders out of circulation for an hour. Data indicate that police and paramedics continue to take overdose patients to closer emergency rooms.

Between July 2021 and March, the stabilization unit served more than 1,800 patients during nearly 3,000 visits. Patients brought themselves for more than 2,000 of those visits.

In the six months that Havrilla and Davidson fell into and out of treatment, overdosing more than a dozen times between them, neither was taken to the unit. They found their way back to care on their own.

Chapter 5: Death and other adverse incidents

If DCF provided online facility information, Havrilla and Davidson might have discovered that a few months before they checked into Aloha for the first time two callers had told DCF that a patient had died after he was given the wrong medicine there.

Aloha had not reported the death to DCF as required by state regulations, according to the callers.

Both callers said another patient had received the wrong medicine the same day but had not required emergency services. The second caller added that Aloha was “more focused on the amenities offered as ‘selling points’ to recruit patients,” which included paid flights to Florida and outings to the beach and was “less focused on providing treatment.”

It was the failure to report the death, rather than what led to the death, that caught the attention of a DCF staff investigator, who responded by conducting a “remote chart review.”

DCF staff did not visit the facility to determine whether, or how, medication errors had occurred. DCF asked facility staff to compose their own “corrective action plan.”

Aloha described a series of steps to avoid future medication errors, better monitor patients and report adverse medical incidents.

Its response also asserted that no medication error had occurred.

Aloha promised to train new hires on a professional code of ethics, assign a manager to ask patients if “unethical promises or monetary offers” were made by staff and start a “new curriculum” limiting recreational activities to within the facility.

The agency’s report noted that the death was an “isolated” incident. That was the last reference in DCF records supplied to The Post of the March 25 death.

Delray Beach police had documented many more complaints since Aloha’s licensing.

Police responded to a call in 2021 from an Aloha staff member about a male employee there. A patient, who thought the man was a therapist, had complained that the man described sex acts he wanted to have with her. As a result of the complaint, the male employee had been fired, but then, the patient said, he had called her teenage son and divulged private medical information.

The female staff member told police that the man had made similarly sexually vulgar remarks to her as well and that another patient had reported he had made “extremely inappropriate sexual comments” during group sessions.

A week after the first call, the female staff member called police back to report that now she was getting threatening and increasingly graphic text messages that she believed were from the former employee.

The man was not charged in connection with either report, and The Post is not naming him. No record indicates that he has credentials as a therapist.

Aloha told The Post that he had worked as a “group facilitator” and that human resources staff had vetted his credentials and references before hiring him.

In the beginning of 2022, a woman in Illinois whose son was on his way to Florida to detox at Aloha called police because while the insurance company said that his treatment there had not been pre-approved for coverage, a staff member at the facility insisted it was. The mother worried that the place was not “legitimate.”

Her report was referred to the Delray Beach police officer assigned to the addiction recovery task force, but a few months later, the department withdrew the officer from the team, citing staff shortages.

Aloha staff said they could find no record that the patient had stayed there at the time of the police report.

About a month after receiving the report of the patient who had died, DCF received the one other complaint it could find about Aloha.

This time, a patient called to complain about the food, housekeeping and the therapy by a counselor who brought her dog to group “free for all” sessions.

The caller also said that she was taken to Delray Medical Center by ambulance after passing out and hitting her head.

A DCF representative emailed Aloha asking to see documents regarding only the food, housekeeping and therapy.

This time a DCF representative visited in person, saw a cleaning service at work and concluded that the complaint was unfounded.

DCF’s subsequent report did note that Aloha had not reported the injury as required. It did not, however, say the same violation had occurred a month earlier after the death of the patient reportedly given the wrong medicine.

Files provided by DCF to The Post do not include any response from Aloha. Aloha told The Post, “We were not informed about this complaint at all internally or externally.”

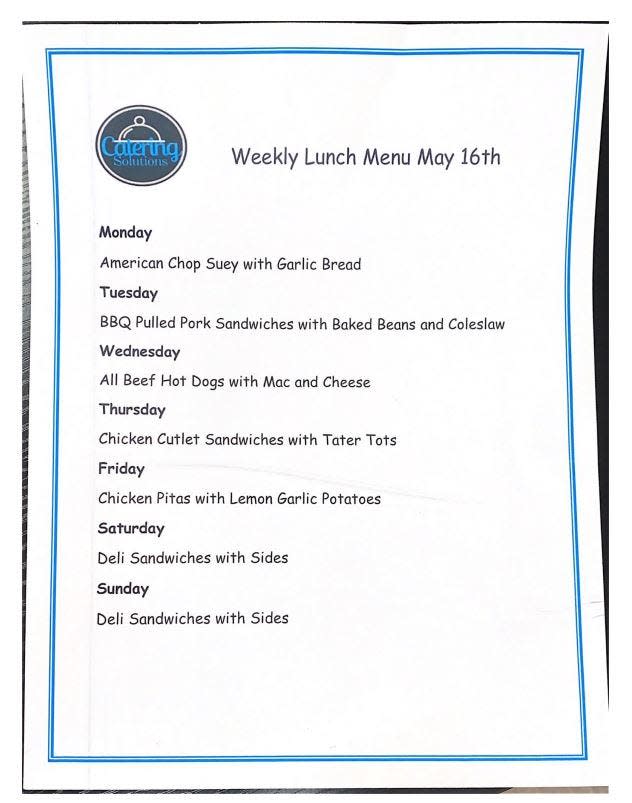

DCF records on the complaint include just a page of a menu from a catering company listing a week’s lunch offerings, starting with Monday’s “American Chop Suey with Garlic Bread.”

Aloha staff told The Post its therapeutic services include individual, group and family counseling, substance use education and life skills training over the course of inpatient treatment spanning two to three weeks.

Davidson recalls none of that.

She remembers the group facilitator who brought her Chihuahua to group sessions and interrupted patients when they tried to speak.

“That was so annoying,” she says.

Another group facilitator played YouTube videos during sessions called group therapy, Davidson said. They filled the rest of their time at Aloha watching Netflix and playing cards, she said.

“I don’t know what treatment is,” Davidson says now, “but that wasn’t it.”

She shared rooms throughout residential treatment with patients undergoing the first terrible days of detoxification, an experience she calls “very triggering.”

Aloha staff told The Post that patients in residential recovery never share rooms with patients undergoing detox.

But Davidson remembers that patient complaints about the arrangement were acknowledged by staff.

“You feel helpless in addiction,” Davidson says. “You shouldn’t feel helpless in treatment.”

She and Havrilla left against medical advice but returned.

The facility discharged them in August 2022 and directed them to intensive outpatient treatment at Pivot Treatment and Wellness on Singer Island.

Chapter 6: A turning point

Pivot’s founder was Delray Beach dentist Dr. Jacob Elefant, who says the gruesome effects of drug and alcohol use he saw among his patients moved him to invest in addiction treatment.

Its cofounder, CEO and training coordinator was Tanya Young Williams, a former "Basketball Wives" reality show star and ex-wife of former NBA player Jayson Williams. His substance use disorder, she said, had inspired her interest in addiction treatment.

Her description of services on Pivot’s initial license applications in 2018, however, shed little light on the treatment the center would provide.

Where Dr. Moran described his center’s intensive outpatient treatment as a minimum of nine, and up to 15 hours of therapy weekly, continuing for an average of 48 days, Pivot’s application provided no concrete details.

“Much of the therapies and psychology that we practice is informed by long-established proven methodologies rooted in Eight Dimensions of Wellness,” Young Williams wrote. “We have witnessed over and over again that making them a part of daily life can improve the quality of life for people with substance use disorders.”

DCF then licensed Pivot to provide outpatient treatment.

The agency suspended Pivot’s license in October 2020 for missing an application deadline but could produce no records of restoring the license.

Records do show, however, that Pivot had three patients when DCF staff scheduled a license renewal inspection months later.

Young Williams had left to open a resale clothing store in New York when Pivot submitted its next renewal application the following year.

Chapter 7: 'Please don't send her to detox over this'

Havrilla and Davidson had been sober for a month when his mother and brother came to Florida for his 25th birthday in early September 2022. Stacey Morris had seen her son through a decade of treatment, including, in desperation, sending him to a wilderness camp for his last year of high school.

He looked healthy and was affectionate and funny, as he always was when doing well. As he hugged her goodbye, he promised he would be OK.

She left uneasy about the treatment he was receiving, she says now.

About a week after Havrilla’s family visited, Pivot patients moved from the southern end of Singer Island to a motel at the foot of the Blue Heron Boulevard bridge to Riviera Beach.

Havrilla and Davidson bought wine at a store across the street from the new Pivot housing, and Davidson had a glass a few days later. Tested on their return to Pivot, Davidson was told she would have to return to detox and inpatient treatment. While Davidson believes she needed intensive therapy, she knew she did not need to detox from the wine she’d had.

She knew she had broken a rule, but the consequence of starting the entire recovery process over again from detox to weeks as an inpatient seemed disproportionate. It also seemed pointless.

“The idea of having to return to Aloha where we had just been for 2½ weeks, held there because our insurance continued to pay, watching Netflix for 12 hours of day, just seemed like torture,” she said.

“Yo, please don’t send her to detox over this,” Havrilla wrote in a text to a house manager. “I’m really worried this will push her to using fent. I know if I had to go to detox I’d actually get high first.”

He wrote that Pivot had made an exception before, which the manager confirmed in a reply.

Pivot staff told The Post they could have sent Davidson to a facility other than Aloha.

Experts agree that a resident who is known to be using an unapproved substance can’t be allowed to stay in a setting intended to be sober — for their own protection as well as the welfare of other residents.

But in the predictable event of a slip among its patients, a center should have a plan to ensure patients have a place to go, West Palm Beach Homeless Outreach Specialist Alexandria Severino said. Many of her clients confront the consequences of failed or incomplete treatment. Leaving without a plan is dangerous, she said.

Havrilla and Davidson crossed the bridge to Riviera Beach and overdosed on fentanyl that night.

Chapter 8: 'I begged someone to help'

Davidson’s car was undrivable and parked outside Pivot. She and Havrilla used it to store their clothes and occasionally sleep. Pivot’s housing was on a side street across from an abandoned building where they sometimes took shelter under an overhang.

It was near Phil Foster Park where Davidson and Havrilla sometimes spent the night under a concrete pier. Across the bridge from Singer Island, Riviera Beach police were conducting a nine-month crackdown on street-level drug dealing.

For most of the next 10 days, Havrilla and Davidson bought crack and fentanyl on the streets of Riviera Beach.

Havrilla overdosed at least five times.

While countywide data show that Riviera Beach paramedics have brought patients to the Addiction Stabilization Unit at least 23 times, its criteria for doing so remain unclear.

Where the department’s responders take patients who have overdosed “depends on a number of factors, but we take them to the nearest emergency room,” Riviera Beach Fire-Rescue spokesman Dawayne Watson said.

All of Havrilla’s overdoses led to St. Mary’s Medical Center, just six minutes from the Addiction Stabilization Unit.

One day after they both overdosed, they returned to Aloha.

“We only lasted two days there before drugs were brought into the facility, and we used them with other patients and got kicked out the next day,” Davidson said.

They returned to Riviera Beach.

As Hurricane Ian spun toward South Florida on Sept. 28, a man they met at the Singer Island 7-Eleven invited them to his brother’s condominium. After an argument with Havrilla, however, Davidson left. Police stopped her as she headed for her car and told her to leave the area in the morning.

They had run out of money and options, and now she did need to return to detox. The next morning, she rang the bell outside Pivot. The manager arranged for her to go to a Lantana facility.

“When I saw Jay for the last time on the morning of the 29th,” she wrote in a timeline of his disappearance she later compiled, “he was trying to pick up more fentanyl, but I was done. He left the car, and I saw him walking over the bridge towards Broadway.”

She believed he would find his way back. He always had.

The facility Davidson checked into sent her immediately to a nearby hospital for treatment of an infection. She spoke to Havrilla from there. He said he wanted to go to detox, too, but the facility that had accepted her had a policy against treating couples together and turned him away.

A man named Mark, who sleeps in an alley near Blue Heron Boulevard, found Havrilla unconscious there that morning and called Riviera Beach Fire Rescue. Paramedics took him to St. Mary’s Medical Center for the last time.

He called his mother from the emergency room, crying. She ordered him an Uber back to Pivot where a manager had promised Davidson she would find a place that would take him.

Narcan, the antidote to Havrilla’s overdose, had sent him into instant withdrawal. When Mark saw him next, Havrilla was looking for drugs.

That night a Pivot patient saw him on the Blue Heron Bridge.

“He was heavily intoxicated,” she told Davidson weeks later in a text message. “He was holding alcohol. He was soooo drunk he dropped it.”

She tried to catch up to him, called Pivot staff, “and I begged for someone to help. But when I went to go get a staff member, they said there’s nothing we can do he’s not aloud (sic) on the property. And I asked them to call the police. And the last I seen he was crossing through the light.”

Chapter 9: The search for a missing man

For Havrilla to be out of touch for a day was unprecedented, Davidson said. She called everyone she could find who had sold him drugs. She got out of the hospital after four days and before checking back into the treatment facility, she returned to Riviera Beach. He had left everything he owned in her car.

Havrilla’s family reported him missing. About three weeks after his disappearance, Davidson caught a ride from her recovery residence to Riviera Beach. In an abandoned bank drive-through where people used drugs, she pretended to be asleep hoping someone would speak freely. She heard a man say that Havrilla was dead.

His family contacted Riviera Beach police and with Davidson, distributed flyers with his picture.

They met Severino, the homeless outreach specialist, who circulated the flyer.

Severino, who has been in recovery herself, has seen people headed for treatment looking for one last high. She also has seen sudden withdrawal from Narcan.

“If you were sick, wouldn’t you want to get medicine?” Severino said.

Davidson compiled a list of everywhere they had been and reported sightings, with links to text messages and phone numbers. She texted the detective assigned to investigate Havrilla’s disappearance.

“I truly believe based on the fact that he had no money or phone when he was last seen that something bad happened to him — either at his own hands or by someone else.”

The detective suggested that Havrilla was alive and near.

Their exchange was the beginning of a two-month near daily correspondence.

Post's award winning investigation How Florida ignited the heroin epidemic

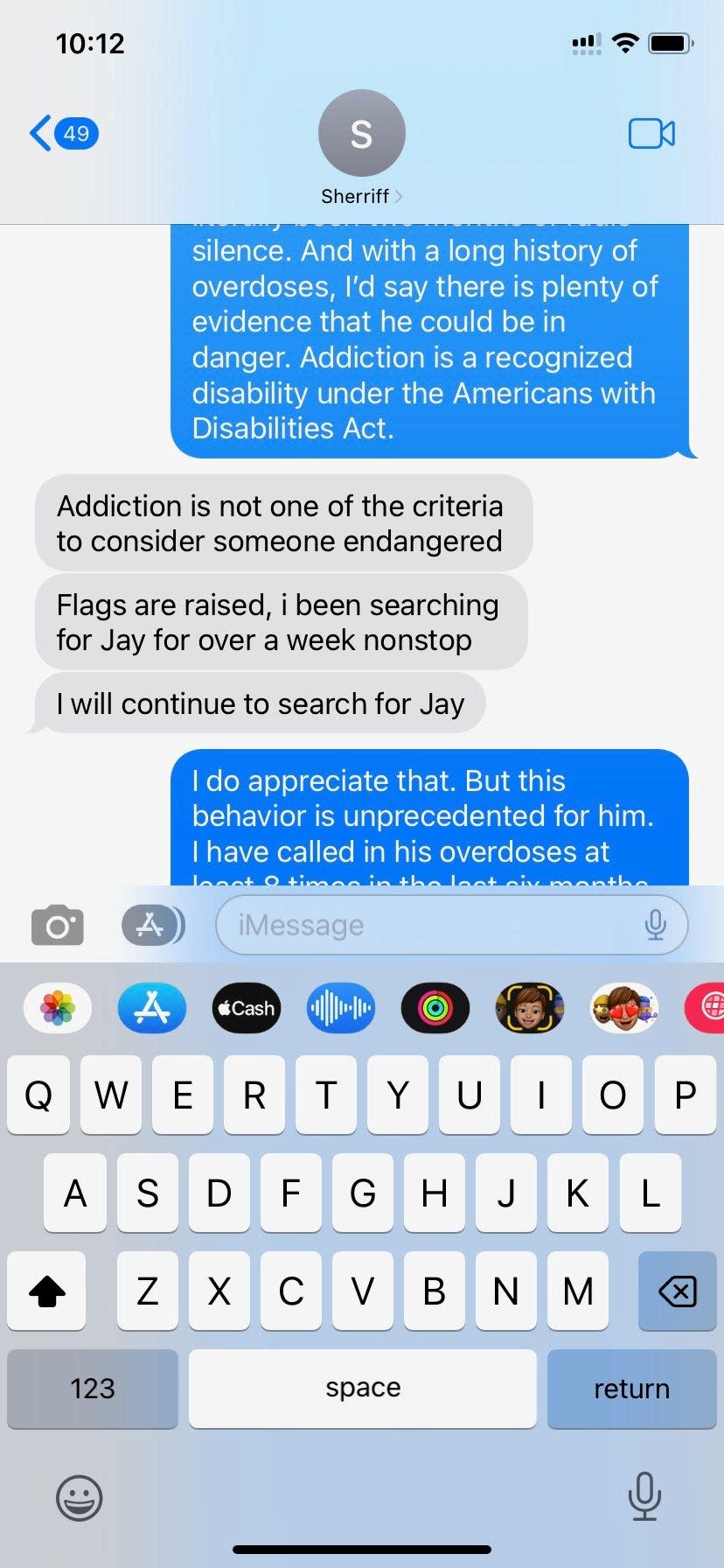

Davidson asked whether his case could be upgraded to “missing and endangered.”

Nothing indicated Havrilla was endangered, the detective replied. “He also does not have any disability that tells me that he is a danger to himself.”

“Addiction is a recognized disability under the Americans with Disabilities Act,” Davidson responded.

The detective explained that addiction does not fall under “endangered.”

He was right, according to a new statewide standard.

Three months earlier, Gov. Ron DeSantis had signed Florida’s “Purple Alert” law to amplify searches for missing people older than 18 who are considered endangered — with one exception: people whose disabilities were “related to substance abuse.”

Including substance use disorders would widen the criteria to the point of making the system “ineffective,” said bill sponsor state Rep. Joe Casello, a Democrat from Boynton Beach.

“If he did overdose and just hasn’t been found, I’m sure he didn’t go far,” Davidson wrote to the detective in early December. “Maybe check around the Publix building?”

Chapter 10: Havrilla is found

Death stops the immune system, unleashing bacteria throughout the body, releasing odors that can be strongest in the first four days and continue for two weeks, said Dr. Thomas Coyne, a forensic pathologist at the University of Florida and interim medical examiner serving seven counties in north central Florida.

Still, a body can decompose close to a thoroughfare and remain undiscovered by passersby, not expecting proximity to a corpse, he said.

“It happens more often than you think,” he said, when the person who died was homeless. Often the discovery is made by someone seeking shelter for the same reason.

Scores of shoppers, including members of a fire-rescue unit who regularly pick up lunch at the Publix on Blue Heron Boulevard, walk through the store’s front doors daily.

A store manager said later that staff members told the police officer working security about a foul odor just outside the front door. A delivery truck driver mentioned the smell of death to people at a nearby business.

In October, a 911 caller reported he could smell a corpse outside the store. He was an undertaker, he said, and he was certain.

The officer who responded left within 11 minutes, reporting the call “unfounded.”

Three months later, in the early evening of Jan. 23, a man with his own history of arrests related to drug use, approached the officer inside the Publix to say he had seen a dead person behind the bushes, just outside the front door.

The Riviera Beach police officer who had responded in October was called back to hang crime scene tape.

“Where exactly was he?” Davidson wrote in her last message to the detective.

We found him in a place where you’d really have to be looking, he told her when she called later.

“You mean a dog wouldn’t have found him?” she asked.

Mark, who had reported Havrilla’s first overdose on the day before he disappeared, learned the man he thought he saved had lain just a block away the whole time. He doubled over, tears sliding down his face.

“He should have had a proper burial months ago,” he said. “That man was just as important as your son or your daughter.”

Epilogue

About a month after the discovery of Havrilla’s body, Publix replaced the dense shrubbery near its entrance with sparser plantings.

The realization that a young man’s body lay behind their landscaping prompted the change, a manager said.

“We don’t want that to happen again.”

From January to the last week of August this year, 356 people had lost their lives to drug overdoses in Palm Beach County.

The addiction recovery task force continues to seek strengthened regulation of the industry.

State Rep. Mike Caruso has led legislation to strengthen addiction fighting and oversight over the past five years. He is driven by his experience with his son, who was lost in the Florida Shuffle for six years before recovering. His son has since informed the efforts he makes to hold treatment operators and the agency that is supposed to oversee them to account.

Amanda Davidson is in California and working. She and Stacey Morris, Havrilla’s mother, stay in touch.

His struggle with addiction is a small part of the caring, funny young man they remember.

“He was so much more than that,” Davidson said.

Morris wants to find a way to bring scrutiny to how people with addictions are treated and protected.

Davidson also wants to see change.

“Say whatever you want about Jay, but you cannot say that he didn't try,” Davidson said. “I think that's one of the most messed up things about the Florida Shuffle. It takes advantage of people who are sincerely trying.”

While treatment programs here highlight a supportive recovery community as they encourage patients to stay in Florida, she said, Havrilla’s death and the months he went unfound tell a story of chilling indifference.

“I wouldn’t want to live in a community where that was acceptable,” she said, “where a body decomposing outside a grocery store is a thing.”

Antigone Barton is a journalist at The Palm Beach Post, part of the USA TODAY Florida Network. You can reach her at avbarton@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Post: The Florida Shuffle: DCF fails people seeking addiction treatment