Should a Florida state park still honor the Confederacy? Calls for change go unheard

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

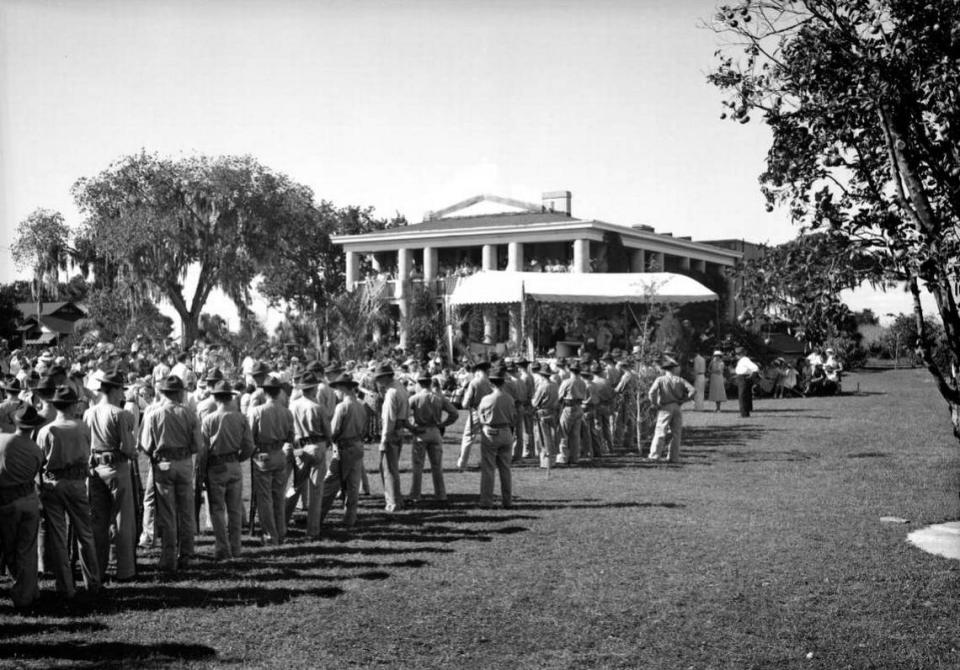

On a sunny spring day at a state park in Florida, the United Daughters of the Confederacy threw a government-sponsored fundraiser.

A poster for the 61st annual Gamble Plantation Spring Open House promised “fun, excitement and learning for the whole family.” It was emblazoned with a Confederate flag.

Another flier from the Florida Department of Environmental Protection offered a chance to “travel back to the Old South.”

On March 5, cars packed into the lot of the Judah P. Benjamin Confederate Memorial at Gamble Plantation Historic State Park near Bradenton.

Visitors wandered the grounds of the oldest building in Manatee County, where historical reenactors in 19th century period costume stood about.

“I Wish I Was in Dixie” rang out on a woodwind. Civil War-era goods and crafts were displayed beneath moss-covered oaks. Confederate and wartime flags flew.

But missing from the day’s events was any detailed mention of the majority who lived at the plantation and built its landmark home: enslaved people.

Walk Gamble’s grounds in 2023, and the decades of slavery that happened there are out of sight and out of mind.

While some plantation sites across the South have updated to include a more accurate representation of their history, Gamble remains a shrine to the Confederacy, its soldiers and leadership — despite many efforts over the decades to bring change.

“I think it’s great,” said Tom Goins, a visitor from Kentucky, said of the open house event. “I’m really surprised there’s not people out here trying to talk it down, because it is a memory of the days gone past and the Confederacy.”

A reenactor displaying a Confederate battle flag said, “I guess by some people it’s used for the wrong reasons. As a kid we used it as rebellious.

“There ain’t been no slavery in over 150 years,” he said, waving his hands dismissively.

In the shade of the Greek Revival-style mansion, crowds lined up for tours.

Inside, UDC members offered insights to the wealthy planter class lifestyle in mid-1800s Florida. The trappings of wealth — fine dishes, crystal, furniture — were preserved and displayed with care.

Lighthearted anecdotes, delivered with Southern tongue-and-cheek, told of the many inconveniences of life for some of Manatee County’s first white settlers.

Baths were a grimy affair. Beds needed frequent delumping. Mosquitoes were a constant menace. And so on.

“The history of the War Between the States is where we’re coming from,” said Peggy Veeder with the Judah P. Benjamin Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC). “We support veterans, we donate to local charity, we have a scholarship contest. We promote history.”

The one-hour tour spotlighted two historical figures: Major Robert Gamble, the plantation’s original owner, and Judah P. Benjamin, the Confederate secretary of state whom the park memorializes.

Gamble, an elite Southerner from Virginia, chose the location, southeast of Tampa Bay and north of the Manatee River, for a sugar plantation.

Gamble first brought 10 enslaved Black men with him. That number had increased to 144 men, women and children by the time Gamble sold the plantation in 1858, and up to 190 by the 1860 census.

On the open house tour, a guide briefly described the classes of slave labor at Gamble: field workers, skilled laborers and house workers.

She described the house worker role as a “plum job.”

“Life was pretty good, as it could be,” the tour guide said, adding that children of enslaved people who worked in the house were often raised with white children of the household.

Then it was on to other subjects.

Missing were any details about how the enslaved people lived, the conditions they labored under, or what they contributed.

One visitor’s impression:

“A lot of the slaves had good lives,” Goins said. “It’s all the lives they had. And after they were free, they had nowhere to go. They had no one to take care of them.”

There is little to support or refute those claims at the state park.

While the exact conditions at Gamble have not been confirmed, historians have found that plantation owners often subjected enslaved people to extreme work hours, brutal whippings, sexual abuse, family separation, inadequate food, meager shelter and the denial of education, among other inhumane conditions.

At Gamble, there is only a ledger of slave names in the visitor’s center and a small sign on the property, next to the white-columned, two-story, 10-room mansion that the enslaved built brick by brick of clay and tabby.

Forever a Confederate shrine?

The United Daughters of the Confederacy purchased the then-crumbling Gamble Mansion and surrounding lands in 1925 before deeding it to the State of Florida.

The gift came with stipulations. A big one: the site must be preserved forever as a Confederate monument, with members of the UDC leading the effort to preserve it. The politically connected group has shaped the telling of the plantation’s history ever since, with the state’s blessing.

The arrangement has benefited the UDC with a place to store its archives, home its state headquarters and host events.

It’s also why the site is designated as the Judah P. Benjamin Confederate Memorial. Benjamin, often referred to as “the brains of the Confederacy” during the Civil War, is believed to have briefly stayed at the plantation as he fled to England after the South’s rebellion failed.

Benjamin was an accomplished lawyer and the first openly Jewish U.S. senator. He was also a slave owner and an outspoken advocate for it.

Some say Benjamin had a change of heart on the matter. As the South faced defeat, he advocated allowing enslaved people to “fight for their freedom” — on the front lines of battle.

Benjamin’s connection with the Ellenton site is small compared to the enslaved people that built and spent many years of their lives there. The details of his stay at the home are surrounded in uncertainty.

“This memorial is dedicated to Confederate veterans,” says a monument raised in 1937. Elsewhere, a commemorative garden has bricks engraved with the names of members of Confederate heritage organizations.

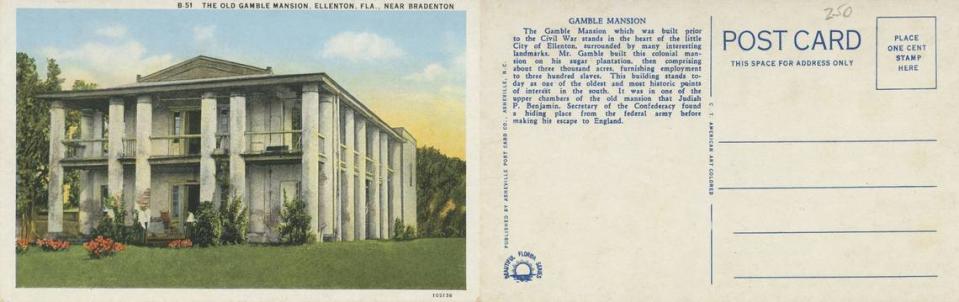

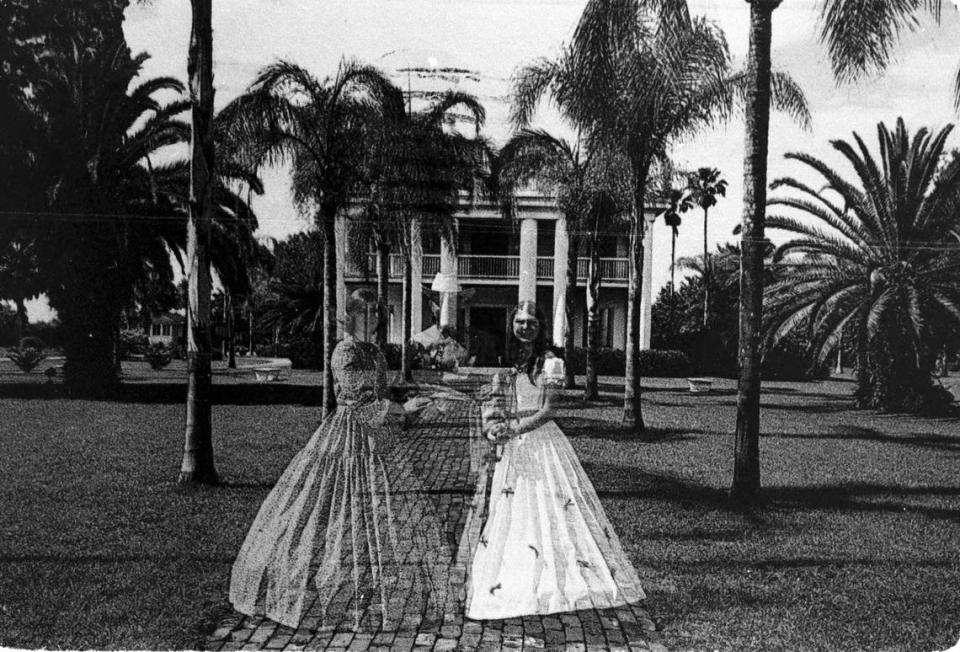

As the grim parts of its history have faded into the background, the home has become an often romanticized landmark.

In the early 20th century, rosy postcards celebrated the mansion’s Southern charm.

“Steeped in legend and tradition it now stands in its original glory as a history reminder of the Civil War days,” one postcard reads.

In the 21st, it is the backdrop for plantation-inspired weddings, Instagram photoshoots, antique car shows and holiday events.

‘It’s problematic’

Some see the park’s current use as a painful whitewashing of the past — one that paints a romantic picture of the pre-Civil War South without fully recognizing the atrocities that are also a part of its story.

“It’s a very exclusionary framework they have there. It’s problematic,” said Diane Wallman, an associate professor of anthropology and scholar of Atlantic slavery and colonialism at University of South Florida.

Wallman led archaeological digs at the site in 2017 and 2018 that unearthed thousands of artifacts from the home’s past.

One of her graduate students, Matthew Litteral, sought out the locations of the slave quarters using a combination of historical records and remote sensing technology. Historic accounts describe dwellings “built of palmetto logs, and thatched with the leaves” and later structures built of tabby.

His research revealed a promising site: a field owned by a private landowner adjacent to Blackburn Elementary School, near the ruins of a sugar mill that was once operated by the enslaved workers.

Other records indicate there may have been slave quarters between the Gamble Mansion and the Manatee River.

“Though high probability areas for the archaeological remains of enslaved houses were identified, no excavations were conducted at these sites due to a lack of landowner interest and skepticism from Ellenton townfolk,” Litteral wrote in his thesis.

No additional excavations have taken place.

However, Litteral and Wallman found that community members and participants in public archaeology field days had a genuine interest in learning more about the lives of the enslaved — if the information was made available to them.

How could Gamble be re-envisioned?

Other parks that have been reinterpreted around the U.S. include the historic homes of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison and former plantation sites like Whitney Plantation in Louisiana and McLeod Plantation Historic Site in South Carolina.

In his 2019 research, Litteral recommended the creation of a new tour script and additional markers at Gamble that include more narratives of the enslaved, as well as collaboration with their descendants.

“Those who were enslaved at Gamble should be represented by more than a list of names scribbled on a bill of sale and tucked away behind glass. The plantation was built upon their blood, sweat and tears, and their story deserves to be told,” Litteral wrote.

Those looking for a more inclusive account of Southwest Florida’s past don’t have to look far. Just across the Manatee River, Reflections of Manatee in Bradenton offers visitors stories of the many groups of people that have influenced the area’s rich history.

They include Native Americans, Cuban fisherman, escaped enslaved peoples who formed the Angola settlement, and pioneer settlers of European descent.

“Our community today is so fractured, and part of that is because people don’t see that they have a shared history,” Reflections of Manatee President Sherry Svekis said.

“I’ve never quite understood how Gamble as a state park can really only concentrate on the glorious plantation building and the life of Robert Gamble and the escape of Judah P. Benjamin without acknowledging the reality of who cleared the fields and who did the cooking.

“I think if we’re looking to try to move forward as a community, we have to understand that every group of people who has lived here has contributed to who we are today and what our community is today.”

UDC’s long history of control

Though the UDC gifted Gamble Mansion and grounds to the state, records indicate that they have maintained a significant say in what happens there over the decades.

For years, the group’s power over interpreting the park was enshrined in state law, which called on the governor to appoint three out of five members of the park’s advisory council from the Judah P. Benjamin Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy.

In order to be a member of any UDC chapter, a woman over 18 must prove she is a descendant of either a Confederate soldier, someone who “gave material aid to the cause,” or another UDC member.

“It shall be the duty of the advisory council to advise the Division of Recreation and Parks of the Department of Environmental Protection in the operation, restoration, development, and preservation of the Judah P. Benjamin Memorial at Gamble Plantation Historical Site,“ said the statute, which was repealed in 2012.

USF researchers found that there have been several attempts to expand the historical narrative at Gamble. But they were consistently met with backlash from the United Daughters of the Confederacy.

“It’s been a long fight. There was one in the 70s, one in the 90s, one in the 2000s. You had Florida Parks Service staff who were interested in changing the interpretation,” Wallman said.

During its first iteration, the Gamble served as a museum to the Confederacy itself, and rooms were dedicated to the different states that seceded from the Union.

That changed in 1977, when State Naturalist Jim Stevenson pushed for the parks system to turn it into a historically accurate house museum with a scripted tour.

“The new script included historically accurate interpretations for rooms throughout the mansion, and emphasized the daily lives and tasks of enslaved laborers,” USF’s Litteral and Wallman wrote in a presentation to the Society for Historical Archaeology in 2018.

But records show that UDC members, upset at the idea of changing the museum from a Confederate shrine, appealed to Thomas Gallen, a conservative state senator. The lawmaker pressured Stevenson and the park system to compromise.

“In the end, the back two rooms of the house were left to be commemorative to Benjamin and Confederate heritage. Many edits were also made to Stevenson’s original tour script by members of the UDC, and in the end almost all mentions of slavery were omitted,” Litteral and Wallman said.

The same tour script has been in use since, the researchers said.

In recent years, UDC members have maintained an influence through the park advisory board, which most state parks have.

The Gamble Plantation Preservation Alliance (GPPA) supplies volunteer power and financial resources and helps decide priorities for the park.

Its current president, Gail Jessee, is founder of the Confederate Cantiñieres Chapter of the UDC in Tampa. Jessee also has helped organize movements against the removal of Confederate monuments around Florida.

“As far as I can tell, every director of the board there has always been a UDC member,” Wallman said. “So they control a lot of what goes on there.”

Jessee and the Florida Division of the UDC did not respond to the Herald’s request for comment.

Documents from the board suggest its leadership may be open to change.

“The GPPA has been working towards improving the interpretive value of the park by developing more information on the enslaved that worked the plantation,” says a report signed by Jessee in 2022. “It’s a difficult task and little by little improvements have been made and more is planned.”

But Wallman and other scholars question what is taking so long.

“I would say they’ve made small baby steps,” Wallman said. “We noticed some shift in the tours, with a little more mention of the enslaved.”

“Those were the majority of the people who were living there,” Wallman said. “But they get maybe a few sentences.”

Small changes ‘at a slug’s pace’

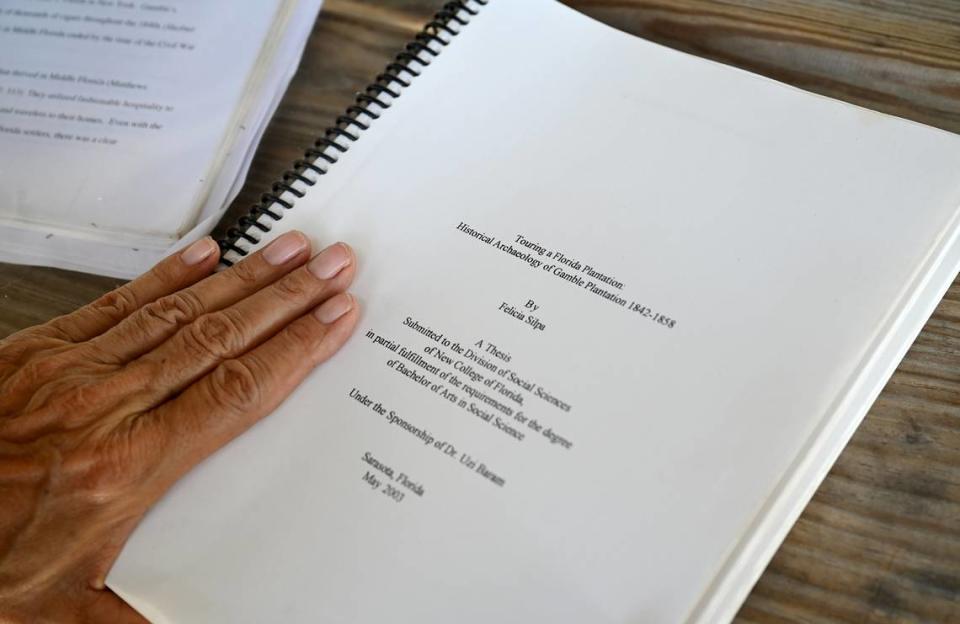

Felicia Silpa is the only member of the GPPA who returned requests for comment. She is not a member of the UDC. The former trauma nurse got involved at the park while she was going back to school to study anthropology.

Silpa now serves as the park advisory board’s archaeologist. She has been studying Gamble Plantation for over 20 years and has published research papers and articles that question the lack of history of enslaved people.

“The Gamble Plantation can move beyond being a repository for the planter material culture to one of a more inclusive historical museum that places African Americans in prominent roles rather than erasing them,” Silpa wrote in her 2008 master’s thesis at USF, which provides an outline of how to make the park’s interpretation of history more inclusive.

Yet almost none of her research and recommendations have been incorporated. Silpa said she has made offers to update the tour script, write additional signage, and help with archaeological investigations, but nothing has happened.

“I don’t know why we’re moving at a slug’s pace,” Silpa said.

“Right now, it’s theater,” Silpa said. “We go in and we have somebody telling us the story. And the story is Gamble. He’s the central character. But we can add other characters. We can add the enslaved, and be honest about what their experience was like.”

In 2020, one update was made at the park that mentions the enslaved. A marker donated by the Gamble Plantation Preservation Alliance depicts what one of the palm cabins that Black inhabitants lived in may have looked like.

The marker offers little detail. Silpa said it’s a step in the right direction.

“I’m proud that we are moving forward. It’s about time,” Silpa said. “But there’s more that can be added to the story.”

Where historical scholars and the UDC can agree is that Gamble Plantation is worth preserving.

Without the efforts of the UDC, the plantation would likely be gone, Silpa said.

Park visitors call for change

State records show that Gamble Plantation gets about 50,000 visitors a year. Calls for change at the park are nothing new.

Visitors, community members, historians and activists have taken issue with how slavery is downplayed at the site. Here are some of their takeaways after visiting:

“While the informed tour guide knew about the slaves who lived here, built the place, and operated the sugar plantation, he only referred to them in response to my questions,” Bernard Leikind wrote in 2016. “There is nothing of slave life on display, and I saw no evidence of archaeological investigation of slave life.”

“Maybe it’s time for the State of Florida to rethink how it is presenting history at the Gamble Plantation,” Robert Plunket wrote for Sarasota Magazine in 2017. “At the moment, it would be an unpleasant experience for African-American schoolchildren.”

“At Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp... imagine if jocular tour guides focused upon the life and times of the Nazi officials, with only a nod to the 1.1 million victims who perished?” Vanessa Hua wrote for the San Francisco Chronicle after visiting the park in 2020.

“It’s impossible to imagine many black Americans — even those who determined that an ancestor had been enslaved at the Gamble property — would feel comfortable visiting the park given its Confederate memorial overlay,” Mark R. Howard wrote for Florida Trend in 2020.

Chandra Carty, a Manatee County woman with direct family ties to a man who was enslaved at Gamble, recently came forward to call for change at the site in an interview with 10 Tampa Bay WTSP. “They obscured what really happened here,” Carty said.

“Slave plantations should be a source of collective shame and sorrow, a historic source of healing, not a space to have a ‘Gone with the Wind’ moment or weddings or picnics,” John Sims wrote in a Tallahasee Democrat opinion piece in 2020. “And the idea that a former slave plantation, as a shrine, as a state park, is being used to memorialize the Confederacy, with taxpayers’ funds, with descendants of African slaves’ tax dollars, reflects a serious breach of moral accountability.”

Sims was a Sarasota artist and former Ringling College of Art and Design professor who in 2020 started a campaign to “rename and recontextualize” Gamble Plantation.

He died unexpectedly at age 54 last December, and Gamble hasn’t yet changed.

But his vision for reinterpreting plantation sites lives on, said Kyeelise Thomas, a Sarasota writer and journalist who is working on a memoir of Sims’ life and work.

“In John’s view, the park was named after a traitor,” Thomas said.

“He wanted to compel people to understand that if you can honor a stranger who was hosted on a piece of land in the state of Florida, surely you can honor the lives that worked, that toiled, that were lost on that land under the plantation system.”

In 2021, Sims teamed up with USF’s Department of Anthropology to host a four part series titled “Monuments, Markers and Memory.” It included a roundtable at Gamble aimed at pressuring the state to change the park’s name and broaden its narrative.

“If we want to move beyond a space of segregation — segregation of stories, of spaces, of spirit — then we need to move back and have a place to tell real stories,” Sims said. “Where those stories are protected and memorialized like all of the dominant stories.”

More than a monument

Like many Confederate monuments, Ellenton’s was established decades after the Civil War ended, during the Jim Crow era of segregation.

Common arguments for creating Confederate monuments include honoring the dead and preserving history. But critics say they were used as tools to rewrite history and uphold notions of white supremacy and “Lost Cause Ideology.”

The Atlanta History Center defines lost cause ideology as “an alternative explanation for the Civil War developed by white Southerners after the war’s end, (that) seeks to rationalize the Confederacy. It claims that slavery was not the central cause of the Civil War. Instead, it claims the primary motivations for secession were threats to the U.S. Constitution and the principle of states’ rights.”

Historians widely agree that slavery was the root cause of the Civil War, and that, whether intentional or not, Confederate shrines served as symbols of white supremacy in a South that continued to subjugate Black people after the Civil War.

“White peoples in power, including former Confederates, enacted racial segregation laws to create a society based on white supremacy — one that mimicked the Southern social, political, and economic order of slavery prior to the Civil War and emancipation. These laws were reinforced by social practices as well as race-based violence,” the Atlanta History Center says in its guide to interpreting Confederate monuments.

In Manatee County, documented cases of racial violence in the Jim Crow era included at least six lynchings and an active presence of the Ku Klux Klan.

“Confederate Statues Were Never Really About Preserving History,” a 2020 project by data journalism group FiveThirtyEight is titled. It found that Confederate memorials started going up by the hundreds in the early 1900s, “soon after Southern states enacted a number of sweeping laws to disenfranchise Black Americans and segregate society.”

“And this effort was largely spearheaded by the United Daughters of the Confederacy, who sponsored hundreds of statues, predominantly in the South in the early 20th century — and as recently as 2011,” the project reported.

One such monument, a 22-foot memorial to Confederate veterans and “the best traditions of the South,” was removed from downtown Bradenton in 2017 after protests for social justice.

The future of the controversial statue continues to be debated.

Commissioners previously discussed Gamble Plantation as a potential home for it, but more recently expressed interest in reinstalling it downtown.

Throughout the South, many monuments like it have come down permanently as sentiment grows that they do not belong in public spaces.

“There’s no joy we find in the Confederate flag or any statue that represents that time,” Manatee NAACP Luther Wilkins previously told the Herald. “To other people, it would be a war that was fought for a family’s livelihood and way of life, but to us, it’s a bitter past. It’s a hurtful past.”

Gamble Plantation is just one example of Confederate symbols and culture that enjoy special protection under Florida law.

Despite several attempts to repeal them, current laws protect the Confederate flag from “improper use or mutilation.” Confederate Memorial Day and the birthdays of Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis are legal Florida holidays.

Juneteenth, the day that celebrates the end of slavery, is only recognized by the state as a day of observance.

Park’s future is unclear

Though the UDC’s influence remains active at Gamble, it’s ultimately the state that decides how its history is presented.

A 2022 report by the Citizen Support Organization makes reference to a possible name change and reinterpretation of the park. But it is unclear if any plans are still in motion.

“In July 2020, we were informed our Park was to be ‘re-interpreted’ as well as a possible park name ‘change,’” says the document, which is signed by GPPA president Gail Jessee. “With this possibility overshadowing any CSO plans coupled with no communication from Tallahassee on whether the GPPA will be included in this new direction, it is difficult to set long-range goals to work toward.”

The state parks system is overseen by the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. When asked if there were any active plans to reinterpret the site in 2023, FDEP did not give a definitive answer.

“The Florida Park Service is committed to providing resource-based recreation while preserving, interpreting and restoring natural and cultural resources, and the agency strives to do this in a positive and appropriate manner,” FDEP spokesperson Alexandra Kuchta wrote in an email.

“Our agency is always evaluating how we communicate Florida’s unique history across all state parks, including at Gamble Plantation Historic State Park.”

The park’s manager was prohibited from speaking with the media.

The park’s next management plan, which includes long-term goals for the site, is due in April 2025. The public will have a chance to give comments and suggestions before the plan is finalized.