Flyin' Miata's 525-HP V-8 MX-5 Is Way More Than an LS Swap

The front straight of the Streets of Willow racetrack is 1000 feet long, and this Miata gathered it up, snapping from one end to the next. The 6.2-liter V-8’s racket and the wind were in a fight to see which could punch in my eardrums first, and the sound of the two going at it broke something in my brain. My eyes and hands told me this was the same plucky Japanese roadster we know and love. Yes, here’s the same tidy steering wheel, there’s that handsome dash, the upright infotainment screen, but that bark and snarl belonged to something else, an aural signature cut from the meanest of Chevrolets and pasted right over this little convertible.

This story originally appeared in the June 2019 issue of Road & Track.

Colorado-based Flyin’ Miata has been making MX-5s go faster for three decades, and while that has traditionally meant bolton forced induction, suspension, and brake systems, FM has also become the go-to for V-8 conversions. The company’s small team of engineers and technicians will build you a turnkey car from any generation Miata you like or sell you the components to assemble your own in the comfort of your garage. This machine, a 2016, is the culmination of everything Flyin’ Miata has learned in its 30 years, and it is not the aftermarket goody basket we’ve come to expect from the company. From engine bay to fuel tank, there are more OEM components onboard this V-8 conversion than in any of FM’s previous efforts.

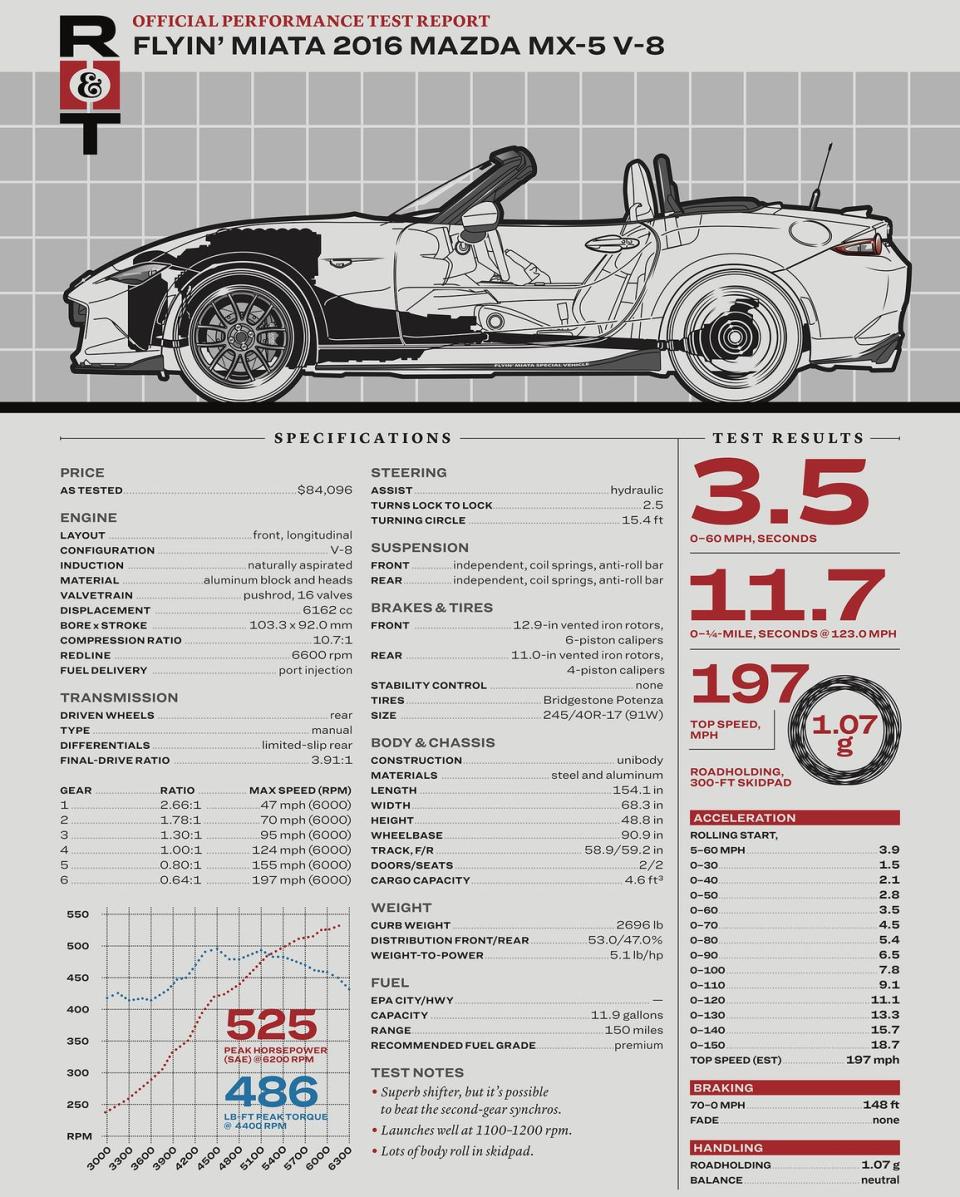

The engines come straight from General Motors as brand-new, zero-mile units, and Flyin’ Miata offers two variants: the wild, 525-hp version in this car and a more civil 430-hp iteration. The only mechanical difference between the two is a General Motors ASA camshaft. Both are 10.7:1-compression mills that suck down premium fuel by the bucket. The Miata’s 11.9-gallon tank will carry you about 150 miles with some restraint, but good luck with that. Either engine will have no problem punting the Miata’s 2696 pounds through time and space.

Our test car’s 486 lb-ft of torque is narcotic, a swell that starts at idle and does not slack until the 6600-rpm redline. With cold tires on a green track, a quick snap to fourth gear sent the rears spinning, the tail yawing wide. There is no traction or stability control. It turns out that physically wedging the best bits of a Camaro SS under a fourth-generation Miata isn’t the hard part of building a vehicle like this. The tricky bit was getting the vehicle’s network of integrated systems to believe that a stack of its major components hadn’t been ripped out and replaced with parts from an entirely different manufacturer.

“We kept working on it for nearly a year and a half,” FM’s Keith Tanner says. “There’s hundreds and hundreds of hours in that. Hundreds. I could show you the sheer number of data logs I’ve got, trying to figure this stuff out.”

Officially, Tanner is this car’s development driver, but he’s as likely to be on the phone at the home office as he is conniving ways to shove big engines into small cars. He’s one of the driving forces behind FM’s V-8 work, a man who literally wrote the book on Miata speed secrets and became one of the giants of the car’s history when he shoved an LS into his first-generation Miata and raced the Targa Newfoundland. Unflappable. Mischievous. Friendly enough to lend you the radiator cap off his track car but professional enough to ask for it back when you get to the next parts store.

Building this 2016 MX-5 wasn’t like anything he or Flyin’ Miata had done before. Nothing about it was simple. Even the previous-generation car was just a driveline in a chassis, separate components that could be swapped around like Lego bricks, but the fourth-generation, “ND,” Miata is a fully modern vehicle. Every component converses with everything else. The headlights chat with the steering rack. The windshield wipers talk to the driveline. The fuel gauge relies on calculated fuel economy to project an accurate tank level. It’s a delicate structure, and pulling one piece can crash the whole system.

The V-8 car uses a Camaro steering rack with a traditional hydraulic steering pump instead of the electromechanical unit found on the factory four-cylinder car. FM turned to General Motors not for feel, but because the electric motor on the Mazda piece takes up space where the oil pan now lives. The Camaro rack has the correct geometry between its pivot points, and a set of Buick ball joints lets the thing work with factory spindles. But that meant that everything that chats with the steering rack was suddenly very confused.

The solution came in the form of real drudgery. Mazda doesn’t share anything about the MX-5’s software code, which left the engineers at Flyin’ Miata to pull it apart, line by line. “We would pull data logs, do things to the car, look to see what changed in the messages, and then reverse-engineer them so we could feed them back or pass them through,” Tanner says.

FM enlisted MRS Electronic, a supplier specializing in automotive software and electronic components, to help work it all out, including the software tools required to map what the car is doing at any given time. The final result is FM’s magic box.

“We have a CAN gateway that sits in the middle of the system, and it brings in signals from the GM stuff, brings in the signals from the body side from the Mazda, and the signals from the Mazda ECU,” Tanner says. “It blocks some, it modifies some, and it creates some to send those back out again, so that the systems all see what they want to see.”

Traction control is the last unsolved piece of the puzzle. To get it to work, the car has to believe that it can limit torque, which requires the factory throttle body to be present and accounted for. That’s why every V-8 ND Miata has a vestigial four-cylinder throttle body hidden somewhere in the car’s innards, just to fool the vehicle into thinking it has all the necessary bits and pieces.

Not that the car needs its nannies. Once the tires grew gooey, the little roadster became a wonder, a physical manifestation of my lizard self. Flub a corner and want to tighten your line? No problem. Point the wheel and marvel as the Miata hunts down the apex. With so much power and so little weight, the car flashes from corner to corner, here one second, there the next, sometimes faster than you’re prepared for. Too fast? Also not an issue. Hammer on the brakes and the car will stop time, hurling your squishy innards against the seatbelt. There are a total of 20 brake pistons on this thing, a gift of the company’s Big Mama Jama brake kit.

Tanner says FM focused on making sure these machines had as much mechanical grip as possible, and that started with rigidity. Unlike the company’s previous-generation V-8 conversions, which relied on aftermarket tubular-steel pieces to support the engine and transmission, FM wanted to use as many OEM components as possible. Despite its ugliness, the stamped-steel factory K-member in a Miata is much stiffer and more fatigue-resistant than anything the aftermarket can produce. It also allowed the company to use GM engine mounts.

“The polyurethane ones we were using in the early cars, they buzzed, they melted,” Tanner says. “They were consumable. I’ve been through multiple sets on my car.”

There’s a Tremec T-56 six-speed tucked beneath the transmission tunnel. It feels unmistakably mechanical, telegraphing the dance of shift forks and gears up the lever to your palm. The rear subframe is a Mazda unit, heavily modified to accept an AAM rear differential from a Pontiac G8, or a Holden Commodore, if you want to sound exotic. The biggest change is a beefy square-tube bar that spans left to right to help handle the massive acceleration loads. Tanner says the V-8’s torque would rip subframes apart on third-generation cars.

The roadster’s suspension relies on lessons gleaned from Flyin’ Miata’s four-cylinder program, albeit with slightly different spring and damper rates to accommodate the V-8’s added weight. Like the factory car’s, they’re softer than you’d guess, even with 500-pound-per-inch springs up front and 300-pound-per-inch coils in the back. The Fox dampers have a staggering seven inches of stroke in the rear. Larger anti-roll bars on both ends do plenty to keep the car planted, but FM ditched the factory mounting points for reinforced versions.

“They’ve proven to be weak on the factory cars,” Tanner says. Engineer speak for: “We broke some things.”

Anti-roll-bar mounting points weren’t the only sacrifices to the car’s development. Right now, there’s a stubby aluminum driveshaft linking the transmission and the differential, but Flyin’ Miata tested a carbon-fiber unit. It was much smoother right up to the point where it delaminated and shattered. Tanner believes the failure had more to do with heat than torque. Because of the tight quarters under the car, the driveshaft sits a finger-width from the exhaust. Constant heat cycling likely stressed the resin, he says, causing premature disintegration.

What’s more surprising is what hasn’t been changed on the car. The fuel system uses the same pump that feeds the 155-hp 2.0-liter four-cylinder.

“On the new ones, we’re running a Lingenfelter 575-hp engine with the stock fuel pump on this thing, and the numbers are good,” Tanner says. “It’s a good thing, because the pump itself is smaller than most.”

Four-cylinder Miata owners, feel free to brag about your 525-hp fuel pump.

A good car falls away from your consciousness on track. It leaves you to focus on the corner ahead, how to nip a tenth here or push a brake marker there. It stays out from underfoot. The V-8 ND manages that better than most. It’s happy to serve up staggering, effortless speed. With a universe of torque at your disposal, you can pick a gear and leave it there, letting that massive pull yank you around the course. It’s the kind of car that makes you think, One more lap won’t hurt. Ten laps later, you’re saying the same thing.

FM’s engine swap does not overheat. It does not cook brakes or eat tires, even with lap after lap of real speed, chock full of easy, graceful slides out of corners. It should be wild, a fistful of lion mane. Instead, it’s just more Miata, the MX-5 we adore, on amphetamines.

Tanner says it’s difficult to put a price on a complete build because the cost of a donor car varies so widely. Early base-model NDs can now be had for less than $20,000, while brand-new RF hardtops currently hang out around $32,000. Then there are other options that can grow or shrink the price depending on how many boxes you check: things like suspension, brakes, wheels, and tires.

Put all that aside, and the conversion alone costs about $55,000 if you have Flyin’ Miata do the work with all-new parts. The total for car and swap is an eye-watering amount of money, but it buys you a modern Cobra that doesn’t want to bite your face off, that you can drive every day regardless of weather, complete with two-year engine warranty. What else could you purchase, for similar money, that could produce the same reliable, pupil-dilating performance?

It’s a strange thing. Cars of this caliber are seldom as aesthetically subtle. The only machines capable of giving this Miata an honest run up your favorite stretch of tarmac or around your home track are supercars, brash and visually dramatic. Massive wheels. Wings. Doors that point to the sky. All tricks designed to draw eyes and people with deep pockets. This car’s drama is more personal. It’s for the driver, not the world looking on.

We didn’t change the tires. Didn’t so much as bleed the brakes. We just filled the tank and went, leaving Tanner, the track, and the gray Mojave behind. Tanner says FM focused on making the car feel as factory as possible by trying to keep vibrations at bay, but there’s no hiding that V-8. Shuffling through Los Angeles gridlock, the stiff clutch and antisocial idle conspire to make it feel like you’re wrestling a stock car down I-5. It’s glorious and hateful in equal heaps.

Everything works. The air-conditioning, the heated seats, the navigation, even the blind-spot warning system all function as you’d expect. But there’s driveline shudder and engine heat, the vague smell of hydrocarbons. After an hour of lurching through traffic, your left thigh burns with the effort of working the clutch, but when the sea of Prius commuters parts and there’s an open stretch of freeway ahead, every bit is worth it. Put the throttle on the floor and the world melts, taking your meager complaints with it.

As famous as it is, seeing Angeles Crest in the flesh is always a treat: the writhing asphalt, the looming mountains, and Los Angeles splayed out beneath. Cruel weather followed us up the mountain. What began as thin mist shifted to cold rain and snow, the temperature parked at a nick above freezing. Seeing the road doused like that, the ground soaked through and the hills lush, the ridges sugar white, was something else entirely: a reminder that there is no such thing as sports-car weather. So often, the only thing stopping you from getting out and going is you. It should have been terrifying, that much power in a rear-wheel-drive car with no traction or stability control, the pavement half a breath from ice, but it wasn’t.

Treat the throttle with respect, squeeze it open, and the roadster explodes forward. The miracle is how it hasn’t lost any of its playfulness despite wielding nearly three times the power. Everything that makes the fourth-generation MX-5 brilliant hasn’t been dulled by the addition of that sledgehammer engine. If anything, it all shines a little brighter. Nothing about the car feels overmatched or unwieldy. It makes you wonder why no factory sells something like it, why the world’s V-8s find themselves chained to sprawling, heavy sports cars.

The air was cold and damp, the windshield splattered with falling snow and mist from the roadside waterfalls. Hikers who’d come to admire the rare snowfall stared from beneath the hoods of their parkas, not quite sure what to do with the sight and sound of this car, or with me, waving like a fool through the open top. With so much rain, the hills broke loose and tumbled down onto the road here and there, scatterings of rocks and pebbles and mud on the pavement.

Some of the best days of my life have been behind the wheel of a Miata. Long afternoons tearing across Texas in a 1990, the odometer ablaze with more than 300,000 miles. Or running up California’s spine in a 2006, my wife pregnant and laughing in the evening sun. Now I can add one mad afternoon in a V-8 ND to that list, the California hills out of uniform and gorgeous for it. And like those cars, this one is a friend, despite its price tag and performance. It reminds us to breathe. That what the long way costs us in minutes, it grants back in sanity.

Naysayers will bemoan this car as just a Miata. And they’re right. That is what makes it great. Because it’s just a Miata, it is no terrible sin to keep the top down, to let it snow inside as the car goes shouting at the mountains, the smell of fresh water and sage and eucalyptus in your lungs. Nothing about it is precious or rare. Leave those curses to the low-mileage Porsches, Ferraris, and Lamborghinis of the world. Let them languish in their garages. Burn an ocean of gasoline in their stead and wear your stone chips with pride, proof of where you’ve been and what you’ve seen.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos