I Followed Teams of Scientists on a Mission to Save Australia’s Great Barrier Reef — Here’s What I Learned

From a marine rehabilitation cruise line to the region’s only carbon-negative resort, these companies are coming up with innovative programs to regrow coral.

Courtesy of Wavelength Reef Cruises

The Wavelength 4 vessel anchored near Opal Reef in Australia.On a late January day at Opal Reef, about 30 miles off the northeastern coast of Queensland, Australia, something strange was afoot. I was standing on the deck of a 64-foot catamaran amid plastic tubs wired with electrodes. They were full of live coral fragments, slowly being heated in seawater.

“It’s a rapid stress test,” explained John Edmondson, marine biologist and operator of Wavelength Reef Cruises. Designed to mimic the warming waters that have been bleaching the corals in this region for years, it’s one of several ongoing experiments that will help the team safeguard the Great Barrier Reef from climate change.

I was with a group of scientists from the University of Technology Sydney on one of their daylong research outings, during which they gathered data and samples from the submarine gardens. One scientist was looking into how algae photosynthesize and feed nutrients to host corals. Another was studying bacteria, while two Ph.D. candidates captured coral gases, which help determine the corals’ stress levels (the scent of sulfur is a telltale sign of trouble).

Barely 200 feet away from this floating laboratory, dozens of visitors from another Wavelength vessel snorkeled and dove on the crescent-shaped reef while learning about conservation from their own team of researchers.

Tourism, meet science. This is what a visit to the Great Barrier Reef looks like today, where research and commerce work side by side to find solutions.

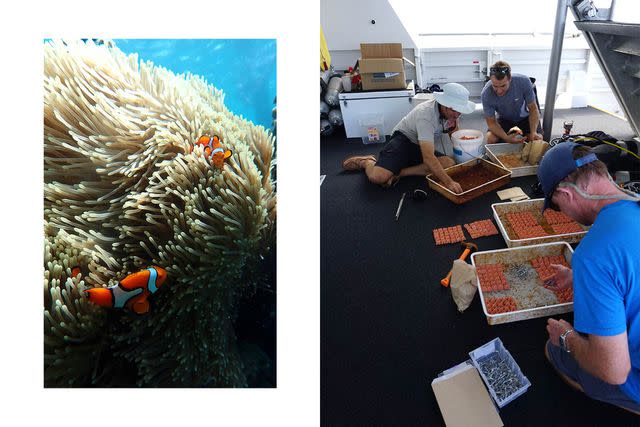

Courtesy of Wavelength Reef Cruises

From left: Clown fish swim among sea anemones; the Wavelength 4 crew puts larvae into settlement tiles, which help them track reef reproduction.Wavelength is one of six commercial operators in the northern reef between Cairns and Port Douglas involved in the Coral Nurture Program, a joint endeavor between scientists and the travel operators whose livelihoods depend on the reef’s survival. The program is an effort to rehabilitate marine habitats, primarily using simple masonry nails and Coralclips, stainless-steel devices invented by Edmondson and his marine biologist wife, Jenny. They attach coral fragments to damaged bommies, an Australian term for reef outcrops. The process looks a lot like propagating cuttings in a garden, except in this case the garden is 1,429 miles long and home to 3,000 individual reef systems, many hundreds of hard and soft corals, and some 9,000 species of marine creatures.

Since the program’s launch in 2018, more than 70,000 corals have been planted, with an impressive survival rate of 85 percent. In November 2021, some of the new corals spawned for the first time. One planted coral fragment can generate hundreds, if not thousands, of corals over a lifetime, said professor David Suggett, cofounder — with Edmondson and Emma Camp, another UTS professor — of the Coral Nurture Program.

James Unswortht

Marine biologist Johnny Gaskell photographs a coral bed in the Great Barrier Reef.To defend the reef, scientists must first understand it. There have been five mass bleachings since 1998, which means that — astonishingly — the Great Barrier Reef has now lost half of its live corals. “Everyone is going back to basics,” Suggett explained. “We have to understand how corals grow, what factors make them grow, all this data that’s been overlooked. Until the bleachings, we didn’t need these tools, because the reef was capable of recovery.”

From Cairns, I flew to the Whitsunday Islands, some 300 miles south. Marine biologist Johnny Gaskell has been busy planting corals and seeding larvae around the archipelago. Many reefs around these 74 islands were damaged by Cyclone Debbie in 2017. Using the “coral IVF” and nursery techniques of larvae management, Gaskell and his team aim to restore what was lost.

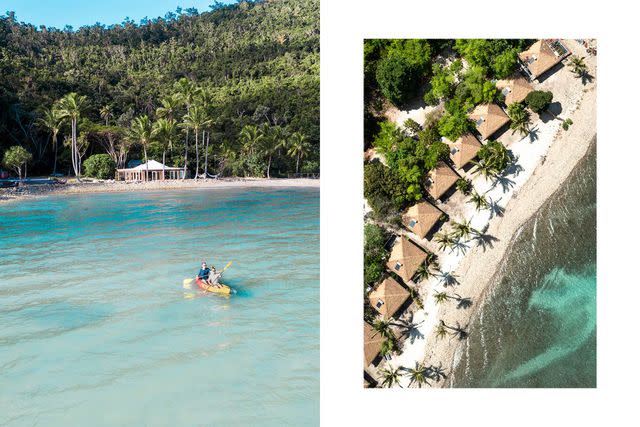

Gaskell and biologist James Unsworth, of sustainable tour operator Ocean Rafting, picked me up on an inflatable speedboat from my hotel, Elysian Retreat, the region’s only carbon-negative resort. Its 10 solar-powered cabins hug the otherwise pristine southern shore of Long Island, a gateway to the Whitsundays.

We sped along to Manta Ray Bay on nearby Hook Island. It’s one of eight sites in the Whitsundays where reefs are getting a helping hand. Gaskell pointed out man-made frames floating deep below where transplanted corals are repopulating the bay.

Courtesy of Elysian Retreat

From left: Kayaking off Elysian Retreat, in the Whitsunday Islands; the 10 solar-powered villas have verandas facing the beach.We also stopped at the Daydream Island Resort & Living Reef, a low-rise, whitewashed property where Gaskell gave me a tour of some land-based coral nurseries before showing me the reef itself: 656 feet of coral that form a lagoon around the property that he had been hired to plan and establish as the resort’s showpiece in 2014. Subject to the same volatile conditions as the ocean itself, this remarkable biosphere — now home to more than 100 species of fish and 80 species of coral — is a bellwether of the health of the Great Barrier Reef as a whole.

Somewhere in this microcosm sits “Steve,” the very first coral Gaskell planted. Since then, coral growth has been so prolific that he struggles to identify his protégé in the wonder wall of sculptural forms. Steve has lived through a cyclone, bleachings, and waves of toxic agricultural sediment flushed into the sea by tropical downpours.

“There’s been ups and downs — it’s been a real roller-coaster ride for Steve,” Gaskell said with a smile. “He became the guinea pig for coral restoration and then had to survive Cyclone Debbie.” If Steve is indeed on the front lines of the reef’s future, then his ability to flourish is good news for us all.

A version of this story first appeared in the February 2023 issue of Travel + Leisure under the headline "Reef Revival."

For more Travel & Leisure news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on Travel & Leisure.