For 40 years, Angels PR legend Tim Mead knew where to stand

Where a man puts his feet constitutes a good portion of his life, and just about all of the job. There’s no guide for it. He knows, he feels, or he doesn’t. The feet lead, the heart and soul lead, they travel together.

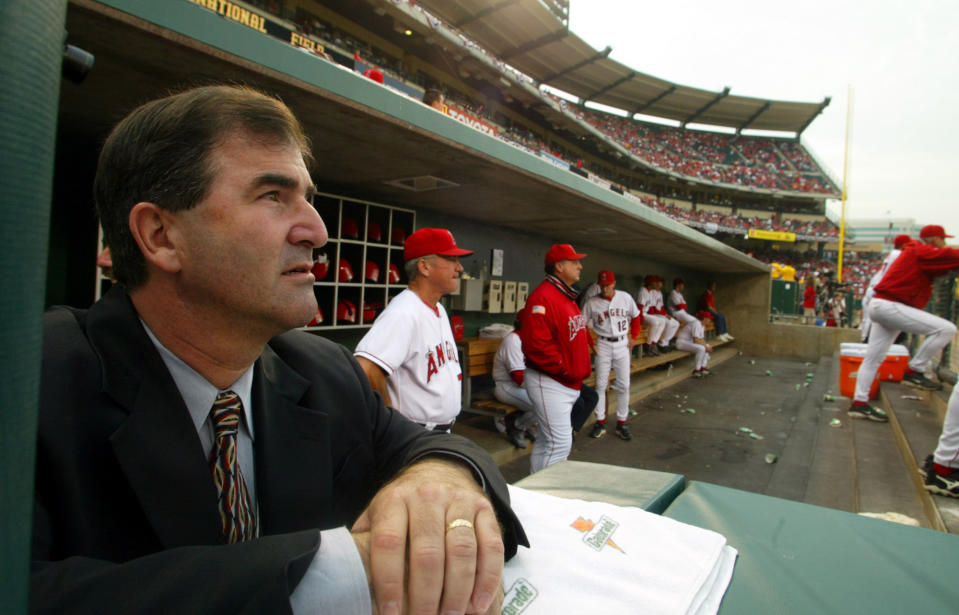

Tim Mead, the California-Anaheim-Los Angeles Angel for four decades, knew where to stand.

On the good days, when grown boys sang and flopped around and celebrated themselves, when they hoisted banners in the name of what they did, he stood in the back.

When the days were almost too sad to take on, up front.

When the headlines were kind, in the back.

When they confronted, accused and scolded, up front.

As the sort of public relations man they don’t grow much anymore, he stood at the front door to welcome the young men getting started, men such as Jim Abbott and Tim Salmon and Mike Trout and Garret Anderson and hundreds of others, and at the loading dock to say farewell when there was no other way to say it, just good luck, just call if you need anything, just let me know.

When it was baseball, plain old baseball, win a few and lose a few and duck the raindrops, in the back.

When it was life, up front.

“I was young and I didn’t always appreciate the impact we had,” said Abbott, who saw the front door and the loading dock more than once. “I was trying to be a baseball player. Tim understood it and taught me there was more than baseball and the game. That there was an impact to be made. … It was always Tim. He was always there.”

On Wednesday, after the Angels host two games against the Los Angeles Dodgers, Mead will pack his office, his red shirts, his memories, his friendships, and leave for a new place, through the front door, to become president of baseball’s Hall of Fame. He is 61. In the month since he said he was going, the refrain from Angels current and former, from baseball writers old and young, from those who’d known him for their entire careers or only in passing, has been some version of, “I can’t imagine the Angels without Tim Mead.”

“I think a lot of folks there are in for a rude awakening,” said Bill Bavasi, the former general manager of the Angels. “I don’t mean that with any disrespect. Every one of them, from the owner on down, appreciate Tim. They get it. I don’t think they know what it’s like when you’ve had that secret weapon for so many years and to go that cold turkey in the middle of the season. I say that with complete love for the Angels. I just know how important that role is to a major league sports franchise.”

Ten years ago, after the Angels drafted their 17-year-old son, Jeff and Debbie Trout traveled to Anaheim. The first person they met there was Tim Mead. And when, two years later, they stood outside Angel Stadium in the middle innings of their son’s first major league game, Mike in the commotion of day one having forgotten to leave them tickets, Mead was the person who raced downstairs to see them in. The Trouts reached their seats in time to see Mike make a running catch in left-center field and 41,000 people rise from their seats to applaud him.

“So I’m with all these other people giving my own son a standing ovation,” Jeff said. “I would’ve missed that.”

There was the time Mead slipped off his shoes on the team plane while playing cards with the likes of Bert Blyleven. He was notified, at that point, in case he’d never noticed, that his feet were as wide as they were long. This is the sort of observation that will amuse the back of the plane whether wholly accurate or not, because having feet like Charlie Brown, who appears to be balanced atop door stops, will always be funny.

This was not the end of the joke. For, so enthralled were those Angels by Mead’s feet, they swiped his shoes. Mead looked everywhere, found them nowhere, and therefore left the plane in his socks, walked through the airport in his socks, boarded the bus in his socks, shuffled into the hotel in his socks and arrived to his room wearing his socks.

Hours later, he answered a knock on his door. It was room service that Mead had not ordered. Another gag, he suspected. Except when the bellman lifted the silver plate warmer, there were his square-ish shoes.

As if, while playing cards, Mead would require a variable beyond cold Charlie Brown feet. Because, even in the decidedly amateurish arena of back-of-the-plane cards, Mead could hardly hide his stress. In poker circles, this is known as a tell. As it related to Mead, it showed in unusually large amounts of sweat. As the pot grew, so too did Mead’s shirt dampen, and often in direct relation to his cards. The worse the cards, the harder the bluff, the larger the puddle. And the bigger the laughs, Mead’s the biggest of them all.

“His integrity,” said Mike Scioscia, who managed the Angels for 19 seasons, not half of Mead’s tenure with the club. “That’s the word that stands out. I don’t know if I’ve met a person in the game, or anywhere, with as much class and character.”

Times changed, the game changed and so the job, in most press boxes, changed. In fact, even the press box changed, in Anaheim from behind the plate to near the right-field foul pole. Tim Mead kept sorting through right and wrong, subtle and not, helpful and harmful and, you may assume, will in Cooperstown as well. When in most cities the public relations strategy began to prioritize gatekeeping, pushing the media further away, digging the moat deeper, Tim Mead re-prioritized facilitation, eye contact and a handshake, remembering the names of your wife and children, recalling that day a since-grayed writer showed up for his first wobbly assignment.

And, well, he probably figured, that’s always where his feet were anyway. It was more honest that way. More helpful. More caring. More professional. Might as well stay there.

In those 40 years, across three owners and under 10 general managers (beginning with Buzzie Bavasi, then serving for four years as assistant to his son, Bill), 14 managers including interims, hundreds of players and coaches and too many knuckleheaded beat writers to count, he became the heartbeat of the place. He toasted fine seasons. He bore up under the terrible ones. He welcomed new families. He consoled players who lost parents. And parents who lost players. Players who lost children. He made a million friends, because he stood not in front of people, or behind them, but next to every one of them.

On the final day of one of those seasons, the manager Doug Rader gathered his players in the outfield. They’d lost more than they’d won. He told them to spend the offseason getting their houses in order so they could be there for the person next to them, to return as the guy who helps someone in need.

“Tim was always that,” Abbott said. “He was always just there for you. His house was always in order.”

That was just part of the life. His wife, Carole. His son, Brandon. Now, even, a grandson. And then, for the game and the people in it, every bit of what he had left. In that, for that, and now on his way to Cooperstown, he stands up front.

More from Yahoo Sports: