Forecasters recall the 'phenomenal' intensity of a storm that was overshadowed by Katrina

|

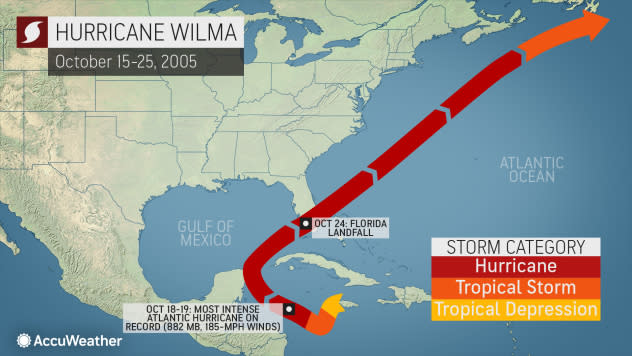

The path Hurricane Wilma took in Oct. 2005 (AccuWeather) |

By the middle of October 2005, the United States had already had its fill of notorious and catastrophic hurricanes. The hurricane season that year was hyperactive, producing storms at a prolific pace that resulted in the majority of the designated storm names being used by the end of September.

The country was still grappling with the horrifying aftermath of Katrina's destruction along the Gulf Coast when Rita slammed into southwestern Louisiana as a Category 3 storm on Sept. 24, bringing even more destruction and turmoil to the beleaguered Gulf region.

As it turned out, the most intense storm was yet to come.

Following Rita came Hurricane Stan, Tropical Storm Tammy and Hurricane Vince. Of those three systems, only Tammy made an impact on the mainland U.S. After Vince dissipated, that meant only one name was left before forecasters would be forced to utilize the Greek alphabet for the first time in history: Wilma.

Although the memories of Katrina might linger more in the minds of many Americans almost two decades after that notorious season, it's Wilma that was the most powerful storm, albeit slightly. Katrina reached Category 5 strength during its time over the open waters of the Gulf, and its peak central pressure was 902 millibars (26.63 inches of mercury). It eventually weakened to Category 3 strength prior to landfalls in Louisiana and Mississippi. Katrina is also one of the deadliest storms in U.S. history. The exact death toll is unknown, but the storm is responsible for as many as 1,200 deaths.

During the second week of October, a broad area of disturbed weather developed over the Caribbean Sea, the typical tropical breeding grounds for the latter portion of the Atlantic basin season. By Oct. 15, a depression had formed, and just several days later, Tropical Storm Wilma was born on Oct. 17, according to the National Hurricane Center (NHC). What happened next was something forecasters still marvel at to this day.

As Wilma took advantage of warm Caribbean waters and low wind shear in the atmosphere, the storm underwent a record-setting and staggering period of intensification. The storm's central pressure peaked at 882 millibars (26.04 inches of mercury), a record that still stands for Atlantic hurricanes 15 years later.

AccuWeather's Lead Hurricane Expert Dan Kottlowski has forecast his fair share of powerful hurricanes during his 44 years with the company. Prior to Wilma's arrival, Hurricane Gilbert in 1988, which pounded Jamaica before striking Mexico, was the most intense storm he ever forecast. Gilbert's central pressure was 888 millibars (26.2 inches of mercury), the record until Wilma came along.

Thanks to their recollections of Gilbert, Kottlowski and his fellow forecasters knew that Wilma would strengthen rapidly and become a formidable hurricane.

"I remember the data coming in [from the Hurricane Hunter aircraft]. I could not believe the drop in pressure," Kottlowski recalled. "Each time the plane went over the storm, the pressure just kept dropping, and we were just wondering, ‘When is it ever gonna stop dropping?' It was wild, you know? That's what I remember the most from Wilma," he said.

"Given that the pressure was still falling at this time, it is possible that the pressure then dropped a little below 882 mb," the NHC said in its post-storm analysis.

CLICK HERE FOR THE FREE ACCUWEATHER APP

Wilma holds the Atlantic record not only for lowest pressure but also for the fastest 24-hour intensification rate on record for an Atlantic hurricane, according to Colorado State University Meteorologist Phil Klotzbach.

It intensified from a 74-mph Category 1 hurricane to a 185-mph Category 5 hurricane in just 24 hours time from the morning of Oct. 18 to the morning of Oct. 19, Klotzbach told AccuWeather.

"That's a phenomenal intensification rate," Klotzbach said.

Klotzbach noted that Wilma's Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE), or the measure of how intense a tropical cyclone is over the course of its lifespan, was 39, a high value but still well below some other tropical cyclones that have prowled the Atlantic throughout the decades. This is because Wilma, while very powerful, was only a hurricane for seven-and-a-half days, he said.

"By comparison, Hurricane Ivan is the Atlantic satellite era (since 1966) single-storm largest ACE generator. Ivan generated 70 ACE but was a hurricane for a whopping 11.5 days and a major hurricane for a whopping 10 days," Klotzbach explained. Ivan was a major hurricane that struck the Alabama Gulf Coast as a Category 3 storm in September 2004.

Wilma would smash into the Yucatan Peninsula as a Category 4 hurricane, devastating the far northern part of the region and wreaking havoc on the country's tourism industry. During its time over Mexico, the hurricane unleashed an astonishing 24-hour rainfall total of 62.05 inches on the island of Islas Mujeres. The storm then spun back out into the Gulf of Mexico and charted a course for the U.S., slightly weaker, but still extremely dangerous.

Based on where an atmospheric component known in meteorological circles as an upper-level trough was situated, AccuWeather forecasters knew the storm would turn to the right and head toward Florida. Initially, Kottlowksi said the team feared it could make a run at the heavily populated Tampa area, but eventually, it struck farther south, impacting areas that had been battered by Hurricane Charley just one year earlier.

|

Powerful Hurricane Wilma as seen barreling toward the Florida coastline on Oct. 24, 2005, with its massive eye visible on a radar loop. (National Weather Service) |

Wilma made landfall as a Category 3 hurricane near Cape Romano, Florida, on Oct. 24. As it tore through South Florida, the storm's eye grew even more enormous, reaching a width of 55-65 nautical miles across, according to the National Weather Service (NWS). That was a distinct difference from the storm's earlier stages, several eyewall replacements prior when the eye was a minuscule 2 nautical miles wide.

Reporting live from the storm

Long before the AccuWeather TV Network was launched in 2015, AccuWeather produced field reports for its website. Back in 2005, AccuWeather Senior Meteorologist Joe Lundberg traveled to Fort Myers, Florida, to cover Wilma, which would end up being the first and only hurricane he would ever cover from the field during his on-camera career.

Lundberg was able to distinctly remember the change in atmospheric conditions before and after Wilma walloped Florida.

"I recall how tropical it felt the day before, as the south to southeastern breezes must have pushed dew points into the mid-, if not upper, 70s," Lundberg said, adding that he also remembered how "chilly" the rain felt as Wilma pulled away from Florida, leaving a trail of wreckage in its wake.

The morning after Wilma, the 12th hurricane of the 2005 season, Lundberg said the aftermath was "devastating." He and AccuWeather Videographer Vern Horst planned to venture south but couldn't get very far due to roads being blocked.

"We were prevented from getting into Naples, as that area [farther] south was hit hard by wind and flooding as Wilma buzz-sawed through the southern part of the state at night," Lundberg said. "Where we were in Fort Myers, there was some damage - trees down, power outages and minor flooding, but areas around Naples into the everglades really got hit hard as I recall."

"As we drove to the Tampa airport to leave later, driving over one of the elevated bridges was nerve-wracking in the strong winds, despite the hurricane basically exiting the southeastern part of the state by then," he said.

Lundberg called reporting on Wilma one of the "highlights" of his on-camera career, but he noted it was quite a challenge broadcasting amid the driving rain and howling wind.

"There was a point at which we felt it was unsafe to report further from outside," Lundberg said. "Fortunately, that was late enough at night that it was time to get some sleep. We then resumed reporting early the next morning as the storm pulled away, but the first report was in a stinging rain. That may have been the worst."

A sense of déjà vu

According to the NHC's report, the number of direct fatalities from Wilma was 23 (although the number of deaths is likely higher when taking indirect fatalities into account). The death toll includes 12 victims in Haiti, one in Jamaica, four in Mexico, five in Florida and one in the Bahamas. Wilma is the ninth-costliest hurricane to impact the U.S. in history with a cost of more than $25 billion, according to the 2020 Consumer Price Index adjusted cost.

Six Greek-named systems would form after Wilma in that 2005 season, but none would impact the U.S. In the following years, the U.S. would still face its fair share of powerful and destructive storms, including Hurricane Ike in 2008 and Superstorm Sandy in 2012, but no major hurricanes would strike the mainland U.S. for more than a decade.

That streak would continue until Hurricane Harvey barreled into the southern Texas coast as a Category 4 storm in August 2017.

"The 11-year stretch that the Atlantic went with no major hurricanes from 2006-2016 was the longest period on record for the Atlantic," Klotzbach said. "The prior record was eight years from 1861-1868." Atlantic land-falling hurricane data from NOAA goes back to 1851, he added.

Fifteen years after Wilma, Kottlowski found himself experiencing a sense of déjà vu. Hurricane Delta followed an eerily similar development path to Wilma in early October, rapidly intensifying in a 24-hour stretch only to eventually batter the Yucatan Peninsula. But rather than head for Florida, it veered to the northwest before slamming southwestern Louisiana.

"Delta formed very close to where Wilma formed. And so, when we were dealing with Delta, I was not surprised that Delta rapidly intensified. It's almost déjà vu with Gilbert and then with Wilma and now with Delta. Delta didn't quite reach the pattern that Wilma did," Kottlowski continued. "In fact, I remember watching the pressure drops in the plane, and I noticed the pressure leveled off. I said, ‘This is different than Wilma.' In Wilma, the pressure just kept falling and it didn't do that with Delta, and so I knew that Delta would not be another Wilma."

Keep checking back on AccuWeather.com and stay tuned to the AccuWeather Network on DirecTV, Frontier and Verizon Fios.