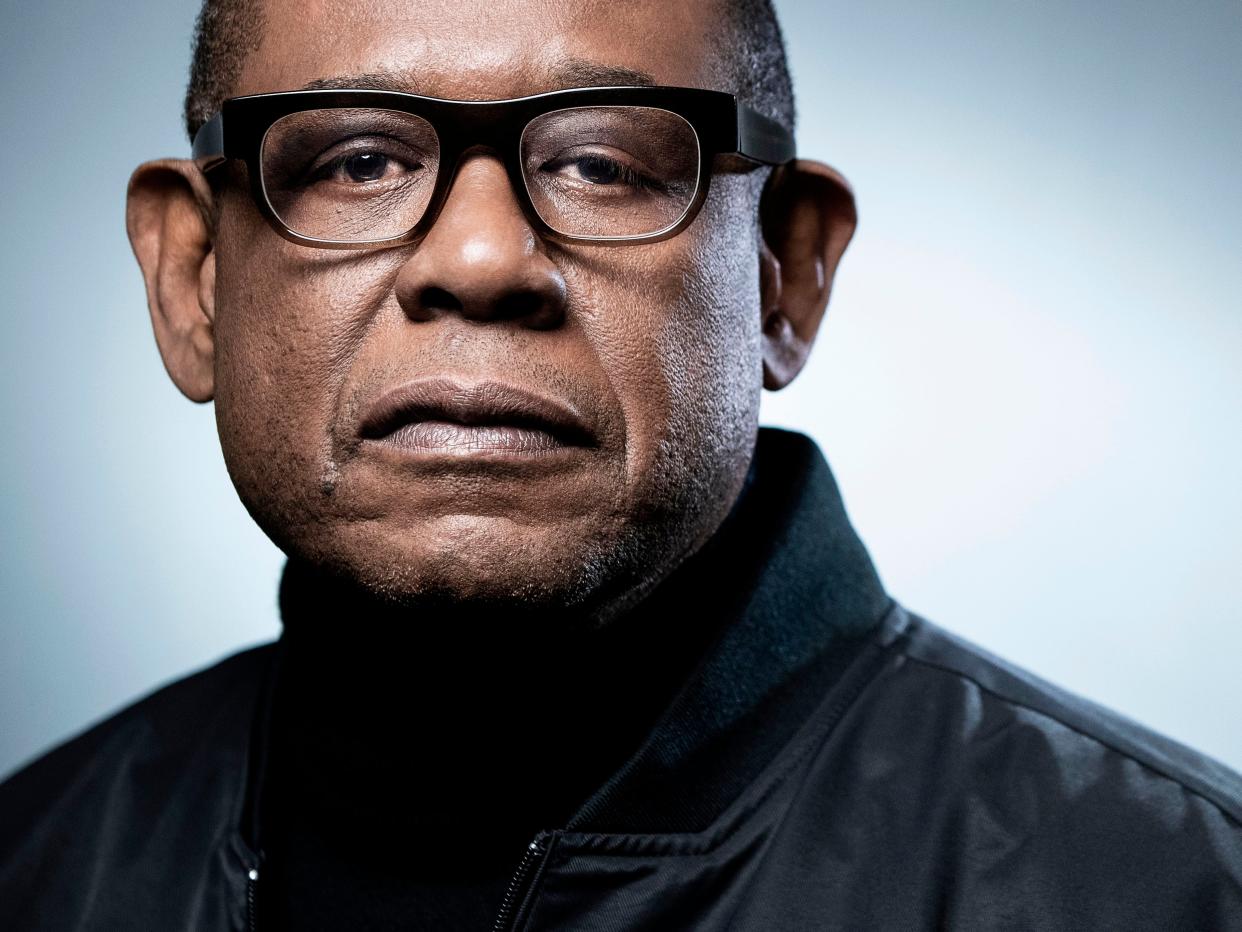

Forest Whitaker: ‘A lot of the issues that they were fighting for in the Sixties are the same now’

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The world didn’t need another mob drama. Or so you may think. The Godfather, Goodfellas, Scarface, The Sopranos: they’ve already barged their way, guns blazing, to the top of most “best films and TV shows of all time” lists. To make another – with the word “Godfather” in the title no less – was surely asking for trouble. But The Godfather of Harlem holds its own. Set against the backdrop of the civil rights movement and women’s liberation, the US series places front and centre the characters usually ignored by the genre. Forest Whitaker is Bumpy Johnson, the real-life gangster who returned from prison to find his Harlem neighbourhood had been taken over by Italian mobsters. Malcolm X appears. So does Muhammad Ali. It’s unflinching and shot with verve; the acting is as seamless as the suits.

“He was a very complicated individual,” says Whitaker of the reckless racketeer. “We wanted to do something about Bumpy, and then we started to discuss this relationship he had with Malcolm X and the collision between the criminal underworld and the civil rights movement. I think it was going to the core of what people conceive the American Dream as.”

The Oscar-winning star of The Last King of Scotland is speaking over Zoom. It’s not the smoothest of conversations – Whitaker has his camera off, and the signal is so bad that he sounds like he’s underwater, though the squeaking of shoes suggests that he’s pacing. We’re here to discuss the show’s first season, which finally reaches UK shores on Sunday on Starz, but it’s been out in the US for over a year so the 59-year-old is far more eager to discuss the second season.

Still, he’s perfectly genial, his voice soft and soporific. It’s the same voice you've heard countless times, one that's capable of conveying a sort of quiet power. It can be harnessed into something sinister – think of him as the roof-dwelling assassin in Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai (1999) or as the home invader who grows a conscience in 2002’s Panic Room. But beneath that broad 6ft 2in frame lies a rich vein of melancholy. In 1992, he was a captive British soldier whose girlfriend is transgender in the Oscar-winning The Crying Game (he’d already played two soldiers before that, with small roles in Platoon and Good Morning, Vietnam). More recently, he starred as a steadfast but confrontation-averse White House butler in The Butler (2013), and as a peace-making Archbishop Desmond Tutu in 2017’s The Forgiven. Though his left eye ptosis renders Whitaker instantly recognisable, he disappears into his every role: a character actor with a star's charisma.

I’ve been asked not to mention the three Ps – the pandemic, personal life, and politics. It’s not that Whitaker isn’t socially active – he was on the Urban Policy Committee for President Obama; he has a foundation called the Whitaker Peace and Development Initiative that trains Sudanese youths in conflict resolution; and is a Unesco Special Envoy for Peace and Reconciliation – but polemics aren’t really his style.

He’d rather say things through his work. What drew him to The Godfather of Harlem, for example, was the chance “to use this backdrop as a mirror for society today”. Take the episode in which a riot breaks out and white police officers begin beating black protesters. “We were really aware of the parallels that were going on,” says Whitaker. “We wanted to stay true to the period, but also bring out the voices that are speaking today, because the issues are the same. A lot of the issues that they were fighting for at the time are the same now.”

There’s another astonishing scene, after Johnson has discovered that his estranged daughter Elise was raped by a store security guard, that deftly skewers toxic masculinity and faux-empowerment all at once. “I woulda killed the guy that done that to you,” says Johnson, thinking only of vengeance. “I would kill any guy that–” Elise stops him. “And what the f*** does any of that got to do with me?” Whitaker says the scene was inspired by the #MeToo movement. In what way? “The notion that you can violate women in any capacity you want, and think that you can move forward without any consequences,” he says. “She’s explaining to him, ‘You don’t understand my experience and it’s not up to you to define or shift it, it’s up to me.’ We had a lot of discussion about wanting women’s voices to be powerful.”

In 2013, Whitaker said something about the state of the world that was, you could argue, somewhat naive. “It’s clear that things are always getting better in one way or another,” he said. “It’s going from living in chains once upon a time to producing the leader of the free world. That’s a happy ending – enjoy it!” Does he feel so optimistic now? Surprisingly, the answer seems to be yes. “There’s certain inequities going on in the world, and abuses, but you can’t deny, as African-Americans, that we are progressing,” he says. “That doesn’t mean that we… we have to look along the line and decide where we are in the journey. [There was a time when black people] weren’t allowed to live in certain neighbourhoods, they weren’t allowed to go to restaurants, they weren’t allowed to own homes… at one point, they were owned. We have to acknowledge those things and those movements, but that doesn’t change the fact that people are suffering through inequities of healthcare, economics, abuses, brutality, those things are still occurring. And so we have to continue to try to correct those problems.”

Back to Bumpy Johnson, then. Though he has moments of humanity – his love for his wife and children is resolute – he is also shockingly violent, slitting one man’s throat and watching another get raped at his command. But Whitaker is no stranger to violent roles. When he played Idi Amin, a role for which he became the fourth African-American to win an acting Oscar, he stayed in character for the months-long shoot. “It was quite tense,” co-star James McAvoy would later recall, “and I felt like I was treading on eggshells the whole time.” “It was terrifying,” said Kerry Washington, who played his wife, “he was scary to be around because he was Idi all the time.” “You get inside the skin of the character,” says Whitaker now. “The way I work as an actor is to dive down deep into the character and then surrender to all the things that I’ve worked on to create him.”

I don’t know whether he stayed in character during his last job before the pandemic struck, but given that it was as a magical toymaker in the forthcoming Netflix film Jingle Jangle: A Christmas Journey, I don’t think it will have traumatised any of his co-stars even if he did. Whitaker laughs. “I’m really proud of it, it’s a special movie,” he says. “I think it lifts the spirit, too.” We all could do with that.

The Godfather of Harlem begins on Starzplay on 1 November