Forever chemicals in Ohio's drinking water: Why Cincinnati is better off than Indian Hill

The industrial pollutants known as forever chemicals turn up in drinking water all over Greater Cincinnati, but how many of them – and how much – flow from your tap depends on where you live.

New data from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency shows the chemicals, which are linked to cancer and other serious ailments, are rarely detected in samples of drinking water from Cincinnati and most nearby communities. But in Northern Kentucky and Colerain and Springfield townships, trace amounts are sometimes found at levels exceeding the EPA's minimum reporting limits.

Water districts that serve Indian Hill, Terrace Park and Loveland found the largest amount of forever chemicals in the area, with some samples measuring three to four times the reporting limits.

The severity of the problem varies across the country because forever chemicals, also known as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, aren’t evenly distributed and don’t respond the same way to all methods of water treatment.

While local officials say drinking water here is safe and meets current federal health and safety standards, they acknowledge PFAS chemicals are a looming problem in communities where they show up in the water.

Scientists are increasingly worried about the threat to human health, linking long-term exposure to an increased risk of cancer, developmental disorders and problems with heart, kidney and liver function.

But there's a financial threat, too. Proposed EPA regulations, which could be in place as early as next year, would force water treatment plants that don’t already remove some of the most common PFAS compounds to install expensive equipment to do the job.

“It’s a big deal for the city,” said Loveland City Manager Dave Kennedy. “How do we fix it moving forward?”

Water testing in Loveland, which runs its own water system, found two PFAS chemicals in the drinking water, one at levels four times higher than the new regulations proposed by the EPA.

Kennedy said the city has hired an engineering firm to study ways to bring its treatment plant into compliance if the EPA adopts the more stringent rules. He said he doesn’t know how much it would cost, but he’s bracing for bad news.

“This is going to be an expensive endeavor,” Kennedy said.

From frying pans to clothes, PFAS are everywhere

Those who study PFAS say any discussion about the chemicals in drinking water must include a caveat: PFAS compounds aren't just in the water.

They’re in the nonstick coating of frying pans, the flame-resistant material used to make carpets and clothing, waterproof fabrics such as GoreTex, and even food wrappers. If you own a home or work in an office, odds are good you encounter PFAS chemicals in some form or another every day.

“PFAS is everywhere,” said Jason Adkins, the public works superintendent in Indian Hill.

Drinking water is now a focus of the EPA and environmental watchdogs because it is perhaps the most direct way the chemicals can enter the body. And once they do, they tend to stick around.

Susan Pinney, director of the University of Cincinnati’s Center for Environmental Genetics, said the half-life of PFAS compounds – the amount of time it takes the chemicals to lose half their toxicity – is about four years in the human body.

Because they take so long to break down in the body and in the environment, the amount of toxicity can build up in people who are regularly exposed to the compounds, hence the name “forever chemicals.”

Water is a primary source of that exposure. For decades, manufacturers of PFAS chemicals all over the country allowed them to slip into rivers, lakes and aquifers that serve as sources of drinking water for millions of Americans. A USA TODAY analysis of the EPA’s data found that water systems serving 46 million people contained PFAS above the federal reporting limits.

The movie “Dark Waters,” based on the work of Cincinnati lawyer Rob Bilott, tells how PFAS contamination in the water became linked to cancer and other health problems over several decades, leading to lawsuits against manufacturers and a $13.7 billion settlement with public water systems.

Cincinnati and other cities across the country are part of that settlement because they deal with the consequences of PFAS every day.

"It's disturbing, frankly, to see the scope and scale of the damage," Bilott said.

But that damage impacts some communities and water supplies far more than others. Geography and technology are big reasons why.

Some treatment plants are better than others

Some sources of drinking water have less PFAS contamination because they're located farther from the sources of the pollution, and some treatment plants are much better at getting rid of the chemicals.

Greater Cincinnati Water Works, for example, operates two treatment plants. The largest, which draws from the Ohio River, supplies water to almost 1 million people in and around the city and uses a state-of-the-art system to remove harmful substances.

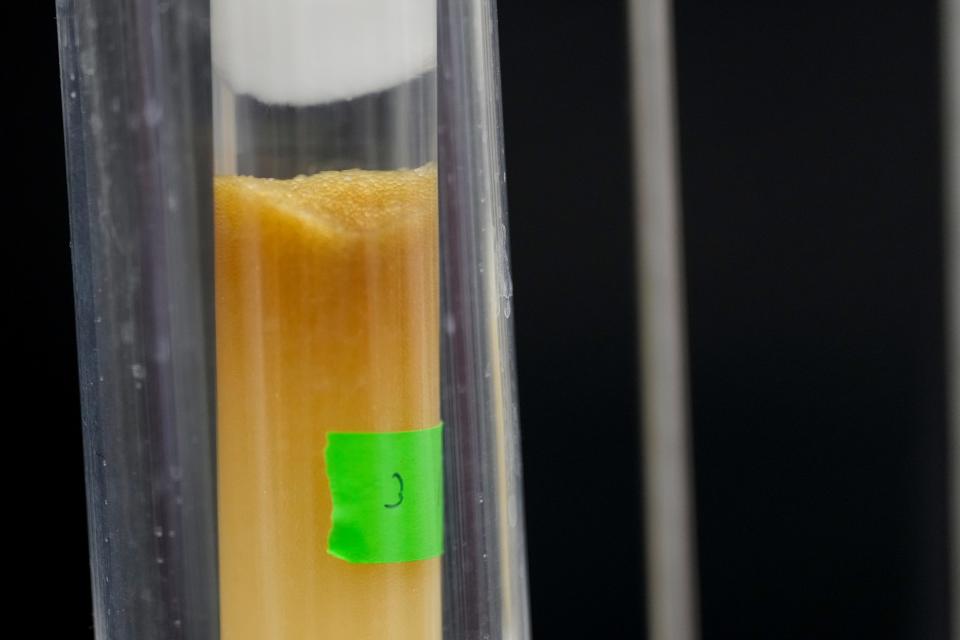

Coal that's been crushed and cooked at high heat soaks up the chemicals, making PFAS undetectable in water flowing out of the plant, said Jeff Swertfeger, Cincinnati's superintendent of water quality.

But it’s a different story at Cincinnati’s other plant, in the northwest corner of Hamilton County. That plant, which serves less than 200,000 people in and around Colerain and Springfield townships, draws water from aquifers and uses more traditional treatment methods.

The EPA found two PFAS compounds in that drinking water at levels just over the proposed limits. Swertfeger cautioned against overreacting to the findings.

“It’s important to remember that these health levels are based on a full lifetime of exposure,” he said. “It’s not something that’s an immediate threat to people’s lives, but it’s something we’re really watching.”

PFAS levels in Loveland and Indian Hill, which also provides water to Terrace Park and parts of Madeira, are similar because they both draw water from the Little Miami Aquifer and use similar treatment methods.

“We have good, clean water. We pass every test without a problem,” said Ricky Gregory, Loveland’s water treatment plant superintendent. “Until they threw this PFAS at us.”

In Northern Kentucky, testing found one PFAS compound in two samples from the water district that serves about 300,000 people, mostly in Campbell and Kenton counties. The highest level was about 50% above the EPA's reporting limit.

Higher standards mean higher costs

The challenge of regulating PFAS compounds is great. Not only are they everywhere, but scientists still are studying how exposure to them impacts health.

The EPA currently recommends that the most common PFAS compounds don’t exceed 70 parts per trillion in drinking water. The proposed EPA regulations would lower that threshold for some of the chemicals to 4 parts per trillion.

Those numbers represent an extremely small amount of chemicals in the water. For perspective, 1 part per trillion is equivalent to a single grain of sugar in an Olympic-sized swimming pool.

But because those chemicals are so toxic, and because they build up in the body over time, the EPA is for the first time recommending that the new limits be enforceable, meaning water districts would face fines and penalties if they exceed them.

How far off are they now? The latest data found levels of one compound at 4.2 parts per trillion at Cincinnati’s northwest plant. In Indian Hill, it was 12.4 parts per trillion and in Loveland it was 16 parts per trillion.

“We’ll put whatever we need in place to meet and exceed their expectations,” Adkins said of Indian Hill’s plans. “Once it’s established, we’ll do our part.”

Overhauling water systems will be difficult, and costly. Swertfeger said revamping Cincinnati’s northwest plant could cost as much as $80 million.

For smaller districts, that could be a deal breaker. Gregory said his first meeting with the EPA about Loveland’s future included a suggestion that smaller districts may want to consider closing their plants and buying water wholesale from big suppliers like Cincinnati.

Norwood, Reading and some other small communities made that change years ago, long before the new PFAS regulations came along.

Every solution comes with costs, said Pinney, the University of Cincinnati researcher. But she said the tougher regulations are necessary. She recently led a study that linked one PFAS compound to delays in the physical development of girls.

"As we continue to do research," she said, "we find there are health effects at lower and lower levels."

That's why Bilott and others want to eliminate PFAS altogether. As an attorney in Cincinnati, Bilott spent decades fighting DuPont, 3M and other PFAS manufacturers while also urging state and federal governments to more closely regulate the chemicals.

He said the proposed drinking water regulations from the EPA are a step in the right direction, but only if the agency gives them final approval and backs up the new rules by enforcing them.

"It's still a long tedious process," Bilott said. "We haven't seen it actually happen yet."

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: Some Cincinnati have PFAS above federal limits