Forget the conspiracy theories — here are the real election security lessons of 2020

The foreign cyberattacks that so many intelligence officials feared didn’t upend the 2020 elections — but this year’s contests nonetheless showed how much the nation still needs to do to fix its security weaknesses.

Paper trails protected the integrity of the votes in closely watched states, thanks to hundreds of millions of dollars in federal aid, but many counties still lack that protection. States mostly rejected the riskiest voting technology — internet balloting — but a few embraced it. And a pandemic-ravaged nation managed to vote safely and reliably, but election offices are still woefully short of money and staff.

Perhaps most of all, this year also exposed the United States’ vulnerability to election threats from within, as President Donald Trump and other leading Republicans promoted discredited conspiracy theories to try to nullify President-elect Joe Biden’s victory.

“The big picture lesson from 2020 is that ensuring an accurate result isn't enough,” said J. Alex Halderman, a University of Michigan computer science professor and leading election security expert. “Elections also have to be able to prove to a skeptical public that the result really was accurate.”

Restoring that trust starts — but doesn’t end — with improving the election technology, policy specialists say.

Joe Kiniry, the chief scientist at the election technology firm Free & Fair, said the U.S. “simply cannot continue” using election systems that “an enormous fraction of the electorate” considers “broken.” Without urgent reforms, he said, “2024 will be a disaster.”

Here are the biggest election security priorities that 2020 revealed:

Replacing paperless voting machines

Trump and his supporters have stirred up distrust about Biden’s wins in Georgia and Pennsylvania, but their failed efforts to scrap those results would have been more effective if the two battleground states hadn’t replaced their paperless voting machines in 2019.

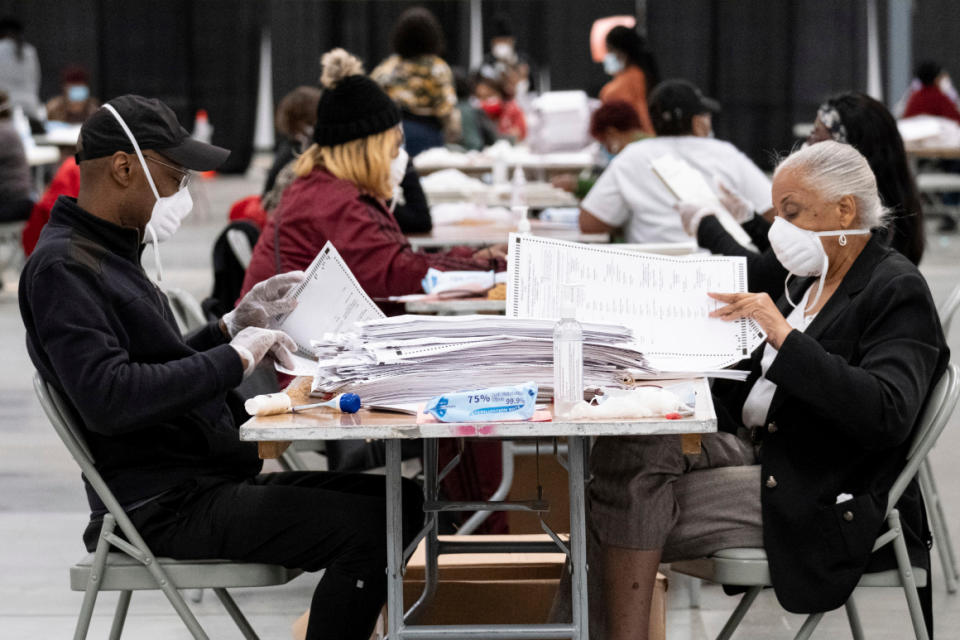

Armed with paper records of every vote, officials in Georgia, Pennsylvania and other closely contested states have been able to doublecheck their results and rule out the possibility of widespread fraud. Paper ballots have been essential in discrediting right-wing conspiracy theories about corrupted voting machines and vote-switching supercomputers.

“That’s why it’s so important to have paper ballots,” Chris Krebs, the former director of the Department of Homeland Security’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, told senators during a hearing Dec. 16. “So even if there was foreign interference of a malicious algorithm nature, you can always go back to the receipts. You can check your math.”

He noted that “Georgia did that three times and the outcomes were consistent over and over and over again.”

But nine states still use paperless voting machines to varying degrees, according to an ongoing POLITICO survey of election offices. In Texas, which is gradually becoming a presidential battleground state, some counties have even purchased new paperless machines in recent years, despite getting $23.3 million from Congress for election security grades in 2018.

Without a paper record of every vote, it is impossible to reliably recount or audit a jurisdiction’s results, because there is no way to rule out the possibility that malfunctioning or compromised voting machines miscounted the electronic vote records.

That could be a serious problem in Texas if, as many Democrats hope, it becomes the next Georgia. And once states or counties have plunked down millions of dollars on new voting machines, they’re typically reluctant to replace them again in the short term.

“Congress missed an opportunity” when it provided states and counties with nearly $1 billion in election security money over two years, said Maurice Turner, who was until recently a senior adviser to the U.S. Election Assistance Commission’s executive director. Namely, lawmakers failed to prohibit them from using the federal money to buy paperless machines.

“As a result, voters in Texas will probably be using paperless systems for the next three presidential elections,” Turner said.

Imposing security standards

Replacing paperless voting machines won’t be enough. Policymakers must also create robust cybersecurity standards for all manner of election equipment, experts on the technology say.

No federal regulations govern the security of voting machines or other systems used to conduct elections, forcing individual states to try to regulate a powerful, highly concentrated industry that has drawn criticism from researchers and lawmakers alike.

The EAC, which Congress created after Florida’s 2000 election debacle, publishes a set of recommendations called the Voluntary Voting System Guidelines. But states don’t have to adopt them, they cover only voting equipment and the agency has not significantly overhauled them since introducing them in 2005.

The results of this regulatory void have dismayed security professionals.

Repeated assurances from election officials and vendors that voting machines are never connected to the internet turned out to be false, as many machines transmit unofficial results over wireless modems. In addition, some machines are programmed by internet-connected computers. Compromising these connections could let hackers corrupt equipment, change unofficial tallies and temporarily sow chaos.

The EAC is close to approving version 2.0 of its guidelines, a landmark update that is expected to ban wireless and internet connectivity. But even those guidelines will cover only voting equipment, such as voting machines and scanners.

Many security specialists have urged Congress to create mandatory standards that are more robust than the EAC’s guidelines and cover the entire range of election technology, including election-night reporting websites and the electronic poll books used to check in voters.

The EAC is considering expanded security assessments for voting systems and ways to test non-voting equipment, but the pandemic has delayed that work.

A partisan divide exists on whether the federal government should even regulate election technology.

Republicans and many election officials argue that the Constitution puts states in charge of elections because they understand their local needs better than Washington does. But many Democrats, backed by leading security professionals, point out that digital threats don’t vary across state lines and note that the Constitution allows Congress to “make or alter” election rules “at any time.”

The future of election security will depend in part on the outcome of this debate.

“The time is ripe for Congress to take up comprehensive election security reform,” Halderman said, “and in particular to set minimum security standards for the administration of federal elections.”

Getting more money from Congress

Lawmakers approved $805 million in security grant funding in 2018 and 2019 and distributed $400 million in pandemic assistance funds in 2020. But election officials and independent observers say states will need much more money on a regular basis to fix their weaknesses and stay on top of future threats.

“Election security and integrity is not something you can invest in only once in a generation,” California Secretary of State Alex Padilla, who is set to replace Vice President-elect Kamala Harris in the Senate, told POLITICO.

The cost of plugging election security holes will be significant. In August 2019, the Brennan Center for Justice determined that upgrading equipment and conducting audits would require “a minimum investment of $2.153 billion over the next five years.”

In 2019, the Democratic-led House passed two bills, H.R. 1 and H.R. 2722, each of which would have provided more than $2 billion for election security over five years, but the Republican-led Senate refused to take them up. Only after months of criticism did Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell offer a $250 million counterproposal, which one Democratic senator called a “joke.”

Election officials also want any additional funding to come without conditions or deadlines, arguing that they know best how to spend money in their jurisdictions.

Expanding risk-limiting audits

Georgia’s complete audit of its voters’ ballots in mid-November confirmed Biden’s victory. It also heralded a landmark moment for a crucial but once-esoteric way of ensuring an election’s integrity: the risk-limiting audit.

Risk-limiting audits reduce complexity by using a statistical formula to determine how many ballots must be checked to verify the accuracy of the results. In contests with large margins of victory, this method dramatically speeds up the process by letting officials check a tiny subset of ballots.

Because of the presidential contest’s small margin, the required sample ended up being so big that officials decided to check every ballot instead. But the fact that Georgia still followed the new, more sophisticated process is the most important part, according to election professionals.

“Where hand recounts in the past have been interrupted by legal arguments and inconsistent procedures, the rigorous methodology of RLAs shows that an audit can be performed quickly and objectively,” said Ben Adida, the executive director of the voting technology startup VotingWorks, which has helped Georgia and other states conduct these audits.

Risk-limiting audits have gained ground since Colorado conducted the first statewide one in 2017. Twelve states are now testing or using them, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

“I'm very hopeful that we'll see 20 states run RLAs by 2022,” Adida said. “We're talking to more states but we also make a point of letting each state announce when they're ready.”

Halting the push for internet voting

By scrambling election planning and making it dangerous to gather indoors, the pandemic gave supporters of internet voting the perfect opportunity to promote the technology. Internet voting promised to spare disabled residents who couldn’t hand-mark a paper ballot from having to visit vote centers, in addition to letting U.S. service members and Americans living overseas cast ballots without relying on the U.S. Postal Service.

By early May, Delaware, New Jersey and West Virginia had announced plans to let people with disabilities vote online in some contests, with West Virginia extending the program to service members and overseas residents.

This news alarmed voting security experts, who overwhelmingly agree that no way currently exists to secure an internet voting system. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine have warned against the technology, and earlier this year, four federal agencies including the FBI and CISA described it as “high risk.” Researchers have uncovered serious flaws in internet voting platforms every time they have studied them.

To security professionals’ relief, online voting did not catch on this year. No other states joined the initial three that announced plans, and those three states backtracked to various degrees.

For future elections, most technical specialists say, improving security will require holding the line against the enticing advances of internet voting firms.

“We are doing all we can to stop the spread of internet voting,” said Duncan Buell, a computer science professor at the University of South Carolina.

Calming tensions between vendors and security experts

Independent security researchers’ ability to test election technology will be one of the biggest factors determining how much that technology improves.

Researchers and vendors have historically had a fractious relationship. Vendors have refused to let researchers test their latest products without confidentiality agreements that can stifle embarrassing discoveries. This forces researchers to buy older equipment secondhand, which leads to vendors dismissing their findings as obsolete.

But as pressure from researchers, activists and congressional Democrats has made resistance to outside scrutiny less feasible, the companies have shifted course. The major vendors are now part of an election security coordination body, and the four largest voting machine manufacturers have established vulnerability disclosure policies so researchers can report flaws in their websites without facing legal reprisals.

The combatants have even become allies of sorts after the election, as Trump and his followers have spread baseless conspiracy theories involving major vendors such as Dominion Voting Systems. Dozens of security experts and researchers signed a letter in mid-November denouncing the claims of vote-rigging.

Still, more work remains to be done. The vendors’ disclosure policies do not allow researchers to actually obtain their products and probe them for flaws. Many technical professionals see that as the next step in building productive relationships with vendors.

“The newest generation of voting systems has not received the same type of scrutiny that the entire previous generation has,” Joshua Franklin, the EAC’s chief technology officer, said at a CISA conference in October. “We've basically gone from two to three public papers from prestigious, well-known cybersecurity researchers … every few years to close to zero nowadays. This is a perilous cybersecurity indicator that I think we need to find a way to change.”