'I forgive you': 2 sisters move past grief to help Manatee County man who killed their brother

Five miles north of Palmetto, a black 1996 Jeep Grand Cherokee came to a screeching halt after rolling over six times. Shattered windshield glinted on the roadway, a car battery and part of the front bumper were strewn behind the car, and the smell of burnt metal wafted from the engine. Florida Highway Patrol investigators found an empty 12-pack of Bud Light beer nearby.

Earlier that day, Jabe Carney and his good friend, Jason Gibson, walked out of their substance abuse rehabilitation center in St. Petersburg. They headed south into Manatee County, stopping by a store to pick up the beer before heading to two bars, including Woody’s River Roo in Ellenton.

After a day of drinking and downing one last Long Island Iced Tea, 22-year-old Carney got behind the wheel in the early afternoon of Feb. 5, 2006.

The decision still haunts him.

Gibson died at Bayfront Medical Center in St. Petersburg 11 days after the crash. Carney was charged with DUI manslaughter and sentenced to 25 years in prison.

A letter from Gibson’s mother was read before the judge during Carney’s sentencing hearing.

“When Mr. Carney got behind the wheel and chose to drive after drinking, he took my son’s life. As I understand it, this was not the first time he chose to drive after drinking. But this time he killed my son, Jason,” her letter said. “When my son died, a part of me died, too, and I’ll never get that back.”

Gibson’s mother has yet to forgive her son’s friend. But less than two years into Carney’s 25-year sentence, Gibson’s sisters, Danyel “Dee” Musser and Katherine “Kate” Duffey, chose forgiveness.

The forgiveness didn’t come easy for the then 19-year-old Musser and 16-year-old Duffey, but they realized Carney's mistake could have happened to anyone, including their own brother.

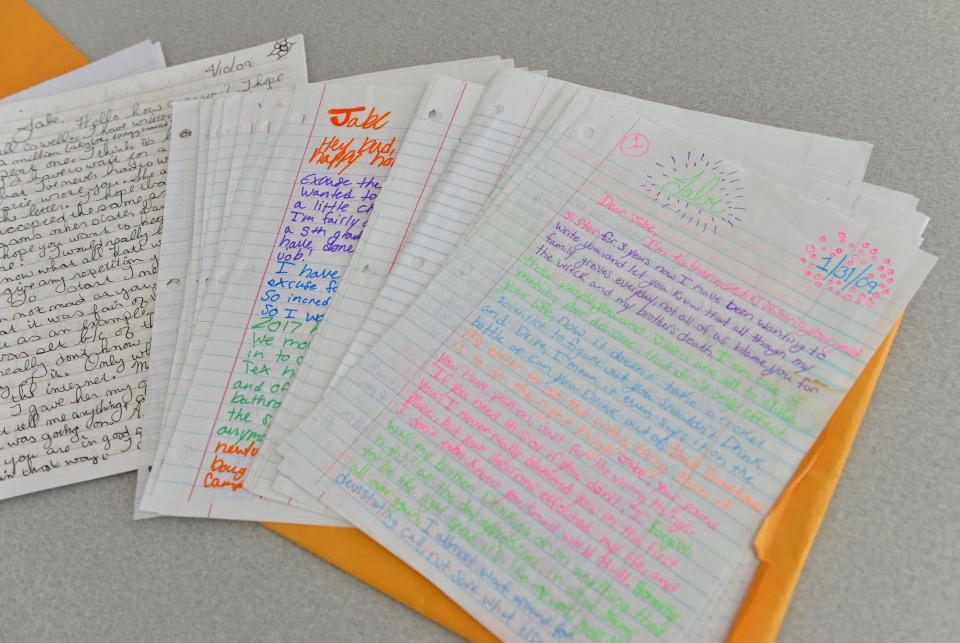

At first, the sisters reached out through hand-written letters which morphed into regular correspondence detailing daily life, big milestones, and sharing stories about Gibson.

It wasn’t until 10 years into Carney’s prison sentence that they decided to work to get him out. By 2018, the sisters felt Carney paid his debt to society while taking total blame for the death of his best friend, even creating a podcast with a Florida professor, all in an effort to highlight Carney’s growth.

Musser and Duffey’s, as well as Carney’s own sister’s forgiveness, marks an example not often heard or seen in reports about the justice system: a lifeline many inmates never see while serving their own sentences.

“Now it’s time for him to get out and be the example they wanted him to be,” Musser said.

The letter that started it all

Carney, now 40, gently slid a neat stack of lined paper from a manilla folder he’d brought with him for his interview one early May afternoon in the visiting area of the Moore Haven Correctional Facility filled with murals of children’s cartoons.

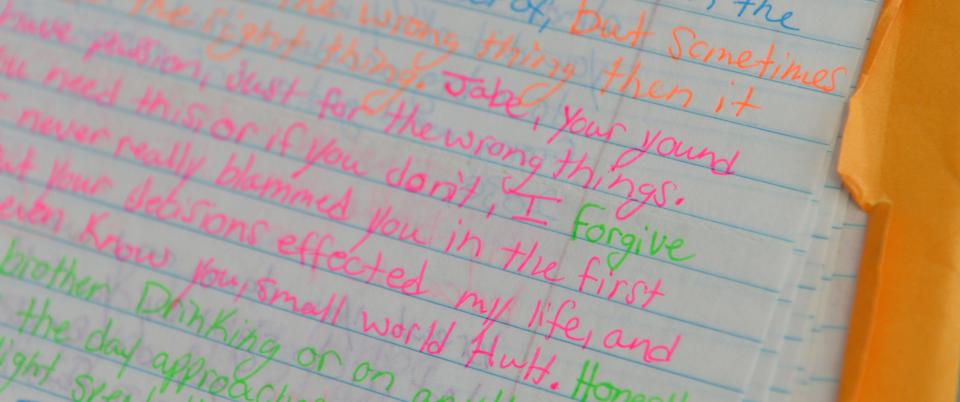

The first sheet was covered in bright neon, the words rounded and compressed together. Among a vibrant pink paragraph towards the bottom of the first page, one lime green word stood out: forgive.

“I don’t know if you need this, or you don’t, but I forgive you,” the line reads in Duffey’s first letter to Carney.

The next letter from Musser included doodled flowers and smiley faces.

Through Carney, Musser and Duffey discovered parts of Gibson they didn’t know.

There were days when they could only feel the anger and pain that came with the sudden death of their older brother. They were just teenagers learning to make sense of a tragedy, but Carney would become a crucial part of their grieving process.

For Carney, their forgiveness has been a catalyst — he’s owned his guilt, he’s become a law clerk and helped many other inmates with their cases, and he’s been a model inmate.

“I’m grateful for their forgiveness obviously, but I mean it's more than that,” Carney said. “I don’t feel like I deserve their forgiveness, much less their friendship and their love, but that’s what they’ve given me.”

It’s not every day that victims’ family members can forgive the person who took their loved one away from them. Yet, Musser and Duffey have chosen to look beyond Carney’s worst decision and focus on his best efforts for improvement.

Otherwise, the world and the justice system seem a pretty bleak place, the sisters said.

Life in prison

Carney sits at a counter checking court documents as a law clerk on behalf of other people who are incarcerated, offering legal expertise and writing legal documents he’s learned through civic courses in prison.

The room is about the size of any grade school classroom, and it’s split in half by a counter that acts as a divider between law clerks on one side and inmates on the other.

The walls are stark white with little relief visually aside from a painted portrait of a judge on the wall near the entrance. It smells like instant coffee and disinfectant.

Six computers line the back wall, giving the law clerks access to Microsoft Office and LexisNexis to help in researching case law to write appeals and other official documents for those seeking help.

On any given day, those in the library will discuss or debate landmark decisions from SCOTUS, the Florida Supreme Court, politics, or theology.

Two long tables sit across from the counter, filled with people fighting for their freedom, looking up the latest law news out of leisure or just looking for a sanctuary from prison life.

It was about 15 years ago when Carney sat at a similar table working on his own appeal to Florida's Second District Court of Appeals, which was shot down in 2009. It’s when he first found his passion for being a law clerk.

He never considered working in the library when his masonry teacher told him that if he wanted to work on his case, he had to learn the law.

Most certified law clerks have their own areas of expertise. For Carney, it’s criminal post-conviction and criminal appeals. For others, it’s civil rights litigation, divorce proceedings, or child custody disputes.

Most law clerks work on two cases a day, but Carney has a caseload of 10 to 20 people.

While waiting to be released, Carney watched those he’d helped get released through his legal services. Even those who are already on the outside write to him for advice.

“To me, freedom is precious,” Carney said. “It is a fundamental, God-given right that we should all cherish and never take for granted. If a person’s freedom has been taken in an unjust manner, then I feel it is my duty, as a law clerk and a man of God, to assist them in their fight for freedom.”

Sean Reilly worked alongside Carney at the law library and saw firsthand how stressful it can be. There’s no shortage of questions or people who need help, and the law clerks try their best with the resources they have. Carney’s humility and quiet strength stood out to him.

In the law library, Carney is reserved, calm, and laid back. He researches painstakingly and speaks only when he has something worthwhile to say. He keeps his word and goes above and beyond to offer help to those desperate for solutions to their legal case.

Carney’s willingness to help everyone was what earned him the respect of many other inmates, Carney’s friend and former fellow inmate Stanley Kropiewnicki said.

“I know, 100%, if I had only trusted him from the beginning, I would have gotten out five years earlier,” Kropiewnicki said, adding it had been too late for Carney to help Kropiewnicki’s appeal case.

Kropiewnicki, 70, remembered the first time he’d met Carney at the Taylor Correctional Institution.

The two had been assigned to the same cell block and had discussed their cases with each other — it struck Kropiewnicki how similar, yet different their cases were.

Kropiewnicki, who is from Poland, was convicted of DUI manslaughter in 2008 in St. Johns County and sentenced to 14 years in prison and one year of community control, according to court documents.

He was shocked when he heard Carney had received a 25-year sentence. Kropiwnicki couldn’t remember a time when Carney had cursed or raised his voice.

During the course of speaking with the Herald-Tribune, Kropiewnicki had trouble expressing himself in English but expressed in Polish how he believes Carney should be released from prison as he no longer sees him as a danger to anyone.

Kropiewnicki was released in 2019, and since then, he and his wife have sent money monthly to help support Carney, who Kropiwnicki has come to see as his best friend and even like a son in the eight years they were incarcerated together.

His early life plagued by the beginnings of the pharmaceutical drug party scene

When he was 13 years old, Carney moved to Florida after his parents divorced. His dad and 15-year-old sister Haley Boyd stayed in Ohio.

The new student at Palmetto High School was quiet and reserved, but he had a magnetism to him that made him popular.

It was 1997, and the opioid epidemic had just hit the area. Friends in high school were excited to try the latest drugs and were experimenting with opioids. It was easy access for Carney, especially following his mom’s surgery for an injury.

Carney was no stranger to the ripples of addiction. Both his mother and father were alcoholics, and his mother had a pill addiction.

David Coughlin grew up with Carney and around the area’s party scene. A whole generation was plagued with this disease of addiction, and Carney was one of the first in their friend group to see its effects.

“Pretty much anybody and everybody I went to high school with has passed away from overdose or is in and out of jail,” David Coughlin said.

He and his brother, Brian Coughlin, were close with Carney during high school. They, too, were not exempt from the epidemic with David Coughlin attending a young adolescent rehab program for oxycontin in his teens and his brother who’s currently experiencing homelessness while battling addiction.

Brian Coughlin and Carney clicked, immediately becoming friends. Brian Coughlin was the class clown and was always goofing around in the three or four classes he had with Carney.

They had completely different families. Brian Coughlin had the TV mom and dad. Carney came from an abusive home riddled with addiction.

But Carney’s mom did her best. She was working hard all the time as a nurse to provide for her kids. She wanted them to be happy and let Carney have free reign on whatever he wanted to do, whether it was video games or other vices.

“She would basically let us have anything we wanted,” Brian Coughlin said. “It was kind of just the idea of, ‘Well if you're going to do it, do it here at the house. So at least I know where you're at.’”

They started smoking cannabis. Then trying whatever was the newest party drug. A nearby pill mill in Tampa opened, making opioids all the more accessible.

They’d pull up to the parking lot of this pharmacy, and there would be 13 different state license plates parked. Brian Coughlin had an MRI that affirmed his back pain, so he didn’t have to pay a couple of hundred dollars for the pills.

“We call them elephant doctors because they literally gave you more pills than anybody else — enough pills for an elephant,” Brian Coughlin said.

The opioids became difficult to stop.

The stigma of addiction built a certain shame inside them, and there was a hunger to feel better. The readily available drugs provided a quick fix for withdrawal effects.

“It was kind of an escape from your problems, but at the same time, you know, the revolving door was like using itself,” Brian Coughlin said. “Nobody thought highly of themselves while they were using.”

Brian Coughlin and Carney stayed best friends from 9th grade up until the crash. He and his mother, Marilyn, would visit Carney once a year for the next five to 10 years. Although he’s happy for Carney and the progress he’s made, Brian Coughlin can’t help but feel like he’s trailing behind the progress Carney’s made while in prison.

“I dread the day when I get to see him because I don’t even know what to say to him,” Brian Coughlin said. “You’re completely reformed and a Christian man and I’m a piece of shit drug addict. This is what you could have had if you just stayed home.”

He’s tried his best to keep his life together, but it’s been a series of ups and downs because of the addiction. He’s kept and lost jobs, been unhoused, and has felt a canyon build between his family and himself because of the disease. But every once in a while the thought of Carney will pop up, and Brian Coughlin is taken aback by how long he’s been in prison.

“I can't believe that his whole life has been wasted,” Brian Coughlin said. “His whole life has been taken away from him. I have lived my entire life, and he’s been in prison.”

Following high school, Carney had his fair share of party benders and run-ins with the law. His family hoped his court-mandated rehab visit at Bridges of America would help him break habits wrought by addiction.

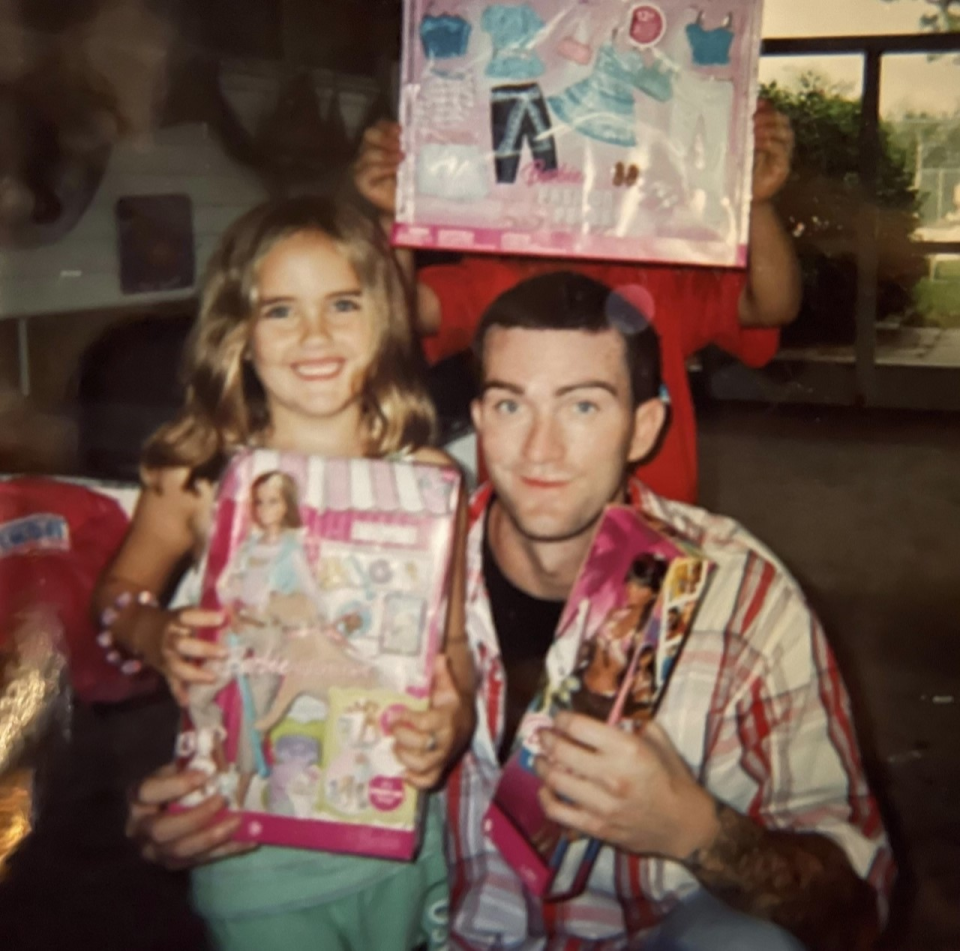

It was there that Carney first met Gibson who had come into the program with little more than the clothes on his back, he said. Carney recalled Gibson had stood alone and it was then that Carney approached Gibson, their friendship starting from that first greeting.

The two moved into a room together and while Gibson took Carney, who was about four years younger, under his wing, the two wrestled with their own addictions as they progressed through the program.

'I wanted him to hurt as bad as he hurt me'

Jason Gibson calls his younger sister Musser from prison. She’s in the 5th grade, and it’s become a routine for her. Every time he gets locked up, he’ll give her a call.

Musser picks up the home phone and hears the prison voice recording buzzing on the line. She hangs up the phone and walks into the other room. Gibson would write her letters, but she didn’t dare write him back. She punished him with silence.

“I wanted him to hurt as bad as he hurt me,” Musser said. “Every time he does this — every time he’s high or in prison and I don’t get to see him — I’m trying to hurt him back.”

It was the era of war on drugs — the era of D.A.R.E. — and Musser and her family were taught to believe that those using drugs were the enemy, including Gibson. They hoped the tough love would help bring back their older brother, their son.

“Instead of trying to help people heal and instead of looking at the reasons why he was doing drugs — what drove him to that, what hurt him to make him turn to drugs to feel like a person worth something, like a human being — we just said no,” Musser said. “You chose that over us, and we’re done with you.”

It took a lot of unlearning and time for Musser to get it. If she didn’t lose him the way that she did, she probably would’ve never understood, she said. She started working at a juvenile placement facility and started trying to save kids. It was her way of trying to make up for not saving Gibson.

As Musser and Duffey got older, they understood how difficult it must’ve been. It was an issue deeper than addiction. It was a mental health issue, and it wasn’t until the last few months of his life that Gibson began healing. It was the closest that he was to his family. Musser would talk to him every night while he was in prison.

He started healing from the hurt of his past and began doing the 12 steps of addiction recovery. He had a difficult upbringing and a lot of truama from the first seven years of his life — things that Musser and Duffey still don’t know because nobody in the family talks about it. As the sisters have gotten older, they’ve pieced together the circumstances that led up to Gibson’s drug abuse.

“Hurt people, hurt people, and that was the cycle he was living in,” Musser said. “I call it generational curses. It started up here, and it just works its way down.”

The sisters have pieces of Gibson scattered throughout their homes. In Duffey’s living room hangs a framed 3-D drawing of a colorful castle Gibson sent her when he was in prison. He was incredibly smart and loved drafting and drawing 3-D buildings. The drawing makes her smile to this day. In Musser’s dining room, Gibson’s hat hangs on a moose rack. Throughout the holiday seasons and decorations, it’s incorporated into everything.

They hold space for the good and the bad — the one Christmas he slept through because of drugs, his teddy bear hugs, the countless times Gibson was in and out of jail when he was kicked out of every school in Venango County, Pennsylvania, the countless times he made them laugh. He was always hilarious. Duffey can hear it now — Gibson’s snicker that would turn into a full belly laugh.

Whenever Duffey is feeling sad, she’ll message Carney and ask him to share one thing about her brother that she doesn’t know. She savors the new memories that are added to Gibson’s legacy. Every once and a while, Carney will ask her for a story about Gibson. It’s harder for Musser to remember good stories of Gibson. She was older. She had a different relationship and couldn’t retain positive memories while the bad ones were overshadowing. Through Carney, she’s been able to remember the good things and pour that into Gibson’s memory. They’ve all been able to preserve Gibson’s memory while also growing closer.

Carney makes it clear that his intention is to never take over the role Gibson had; he couldn’t.

It was through Carney that the sisters were able to begin their own healing process. Duffey said that Carney taking full responsibility for the accident has helped them move toward forgiveness.

Duffey and Musser said that their mom still has her own peace to make with Gibson’s death and Carney’s hand in that.

“She doesn’t have ill will for him,” Duffey said. “She just doesn’t know how to move forward in her grief and anger.

'Always been a good guy'

The first thing Carney remembers after the crash was his girlfriend Angela Doak’s piercing screams.

Gibson swam into Carney’s vision, his face pale and his fists clenched as he laid on his back, Carney recalled, the sunlight filtering lazily into the prison’s visiting area as his leg jostled with nerves.

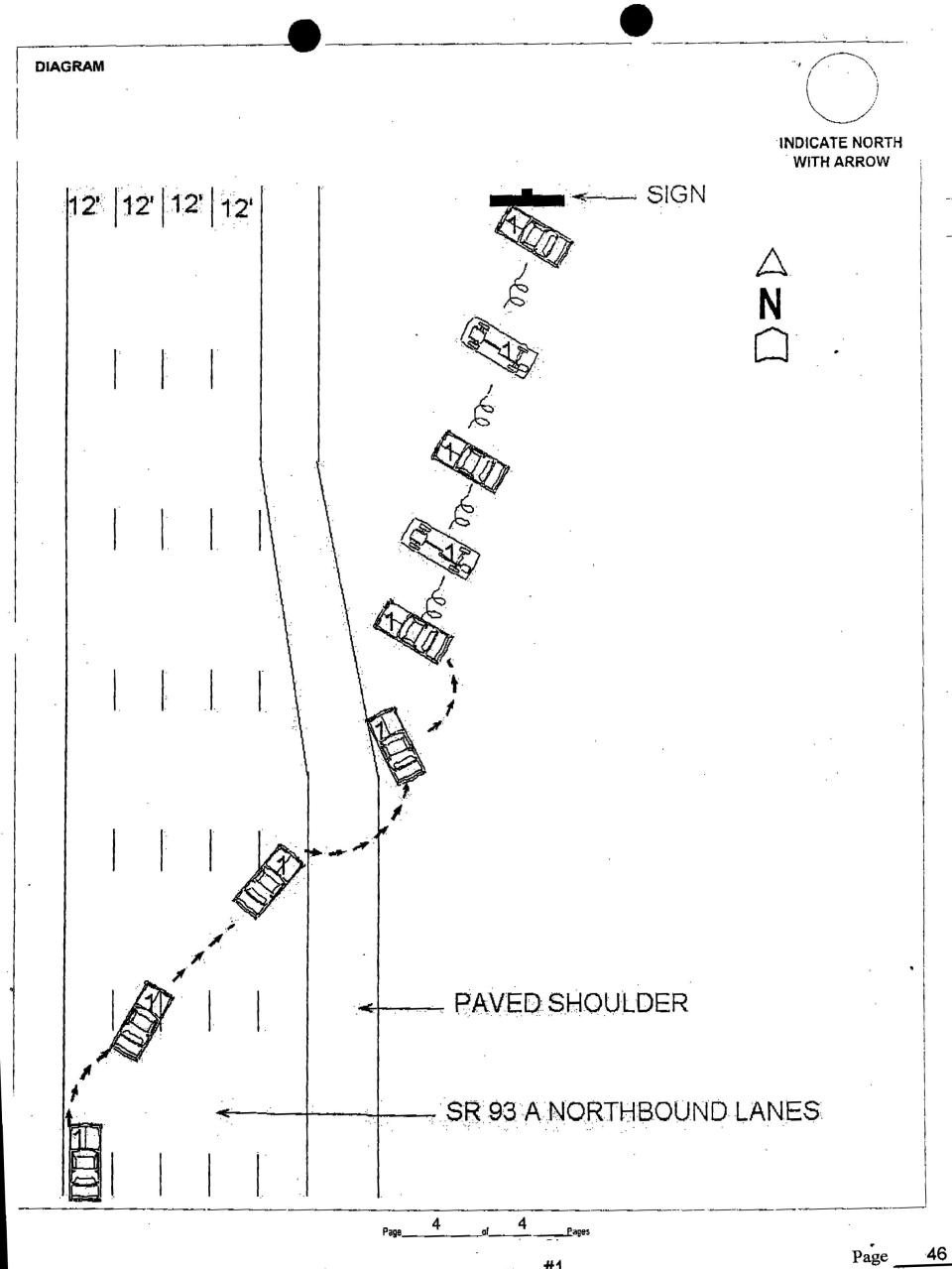

Prior to the crash, Carney said he had been reaching for his wallet to hand Doak gas money and when he looked up, the car in front of him in the left lane had slowed as it approached the Sunshine Skyway south toll plaza. He instinctively pulled the wheel to the right.

Carney lost control of the vehicle as it went into a counterclockwise spin before its tires “dug into the soft shoulder” causing it to overturn before stopping against a signpost, according to a FHP report.

Because all three occupants weren’t wearing their seatbelts, they were ejected from the car. Following the crash, Gibson was airlifted to Bayfront Medical Center. While at the hospital, Carney was interviewed by an investigator.

“I really messed up this time,” the investigator noted that Carney spontaneously said during an initial conversation with him. The investigator observed that Carney had bloodshot and watery eyes, was slurring his words, and could smell a strong alcoholic odor.

A blood sample taken from Carney after the crash and later tested indicated his blood alcohol level was 0.111, or nearly 1.4 times above the legal level.

Carney spent 11 days in the Pinellas County Jail, calling his mother every day to inquire about Gibson, who remained in critical condition. Carney’s injuries included a concussion and torn cartilage in his right knee, he said.

On the 11th day, when he asked his mother about Gibson, she grew quiet.

“I never really talked about this,” Carney said, tearing up as he recalled the moment he learned that Gibson died.

Gibson was one of 1,099 alcohol-related fatalities in 2006, according to a FHP report.

Carney was charged with DUI manslaughter, driving while license suspended and causing serious bodily injury or death, driving while license revoked - habitual traffic offender, and two counts of driving while under the influence which resulted in property damage or personal injury, according to court records.

For almost a year, Carney was held in the Manatee County Jail until he posted a $50,000 bond. It was during that time Carney tattooed Gibson's name onto his right bicep, a permeant reminder of the close friend he lost when he lost control of the car. A little less than seven months later, a bench warrant was issued for Carney after he failed to appear for a docket sounding, according to court records.

Carney said that when he was released, he began to abuse drugs again to cope with the stress of the impending trial. When the judge pulled his bond, meaning he would have to go back to jail, Carney ran.

When he was arrested less than a month later, new charges were added and in March 2008, Carney was found guilty by a jury of charges that included DUI manslaughter and fleeing to elude a law enforcement officer, according to previous Sarasota Herald-Tribune reporting.

At his sentencing, his mother, uncle, sister, and friends asked the judge for compassion in her decision.

Many testified to Carney’s positive characteristics, saying that he’d always been “a good guy,” and would help anyone when he could.

Challenges posed: Why keep Carney locked up?

While Carney has been described as a model inmate and his record shows he’s received only one disciplinary report for disrespect in 2008, he’s faced obstacles with getting released early.

In Florida, prisoners must serve at least 85% of each sentence imposed before they can be considered for early release. In Carney’s case, the earliest he can be released is in September 2026.

To reduce their sentence, inmates can earn up to 10 days of “gain time” per month. Once their gain time reaches what would equal the 15% reduction in their sentence, they can no longer apply the gain time to their sentence.

Carney’s obstacle could also stem from the fact that under Florida law, the primary purpose of sentencing, and the criminal justice system in general, is punishment.

In 2020, there were more than 81,000 individuals incarcerated in Florida prisons, according to research released from Levin College of Law’s Race and Crime Center for Justice. Of those, approximately 15,000 are serving time for murder or manslaughter offenses.

“The system is designed to make people suffer, and it is designed that way because — quite frankly — there are bad actors in the system who have mal intent and want to impose that on other people,” said Kenneth Nunn, a University of Florida law professor at the Levin College of Law.

Nunn expanded that the public expects those convicted of a crime to suffer because they’ve been trained to fear crime by politicians and news outlets who profit by stirring up the public.

Florida is one of 16 states that does not have parole, according to a report by Right on Crime, a conservative criminal justice reform initiative started by the Texas Public Policy Foundation.

In 1983, the Florida Legislature abolished parole for most offenders who were sentenced on or after Oct. 1 that year. As of May 2022, there were 3,670 inmates eligible for parole consideration, according to The Florida Commission on Offender Review’s website. However, Carney is not included in that number.

Another avenue, which can oftentimes be the only way to get early release, is through clemency.

However, for an inmate to even be considered for clemency, they must first submit an application which is first reviewed by the Florida Commission on Offender Review, explained Molly Gill, the vice president of policy for Families Against Mandatory Minimums. After a thorough review, the commission writes a recommendation to the Florida Board of Executive Clemency.

If the commission writes a recommendation denying clemency, and the board doesn’t reverse that decision within 60 days, then the inmate’s request is denied. Gill said many people are often denied without getting a hearing in front of Gov. Ron DeSantis and the rest of the board.

Additionally, the clemency board only meets a handful of times a year. In 2023, the board met twice so far.

Carney applied for clemency in 2019 and five years later in February 2023, his application was denied.

Even if there are officials at state prisons that believe an inmate is deserving of being released, maybe they’ve shown growth or have a good character and could be perceived to be a model inmate like Carney, or maybe they are perceived as no longer being dangerous, current Florida laws prevent them from being released early.

Instead, keeping inmates incarcerated past the point of them being dangerous can become a burden on taxpayers, said Ashley Nellis, co-director of research for The Sentencing Project.

“They're also not contributing productively to society through getting a job, which many of them would like to do if they were to be released,” Nellis said.

The FY 2021-22 Florida Department of Corrections annual report shows it costs $28,298 to house an inmate in a state prison, or about $77.53 per day per inmate.

“There's a lot of people in prison who are more than ready to be released,” Nellis said. “I don't think everybody is, of course, but I think his story is not that uncommon. … That's the problem with these mandatory sentences, or with this sort of erroneous belief that a certain term of years means you're repaired, but sometimes that happens sooner than others.”

Future beyond bars: A light of hope

Carney recently found two cases that could be the key to his release from prison.

In a motion he wrote to correct his illegal sentence, Carney states that the trial court “was statutorily mandated to impose a probationary period following any prison sentence” he received for DUI manslaughter.

However, his 15-year sentence didn’t include a probationary period, thus making it illegal, he states. Since the sentence improperly extended the overall sentence length to 25 years, and he has the support of the victim’s family, a lesser overall sentence should be favored, he adds.

An attorney filed a notice of appearance on May 12, indicating he’s taken on Carney’s case. Two motions to correct his illegal sentence were filed 18 days later.

Carney hasn’t yet fully forgiven himself and he definitely wouldn’t say that he’s deserving of being released early, he said. He hopes to be released so he can do right by those close to him.

He’s nervous about adjusting to life beyond bars but said the first thing he wants to do is see his family and those who stood by him. Kropiewnicki and his wife have already invited Carney to visit so they can take him to an island they recently visited.

As far as a job, Carney said a law firm in Florida has potentially offered him a job, but he wants to move closer to Boyd and her family, maybe work at his brother-in-law’s business.

Duffey hopes that Carney is released soon so that he can live a life her brother in his sobriety would have been proud to see, which she feels Carney has done and then some.

She knows that it won’t be easy and that Carney will surely have tough days — but she and her sister won’t let him fail.

“No one needs to release a black balloon anymore because addiction took another loved one,” Musser said. “We do recover. They will recover. There's a support system out there, and honestly, the best support systems come from the most unlikely places.”

Duffey looks forward to seeing Carney in person, watching him smile and laughing together as he tells her another story about her brother that she hasn’t heard yet.

“Get out. Go live your life,” Duffey said. “Whatever you do, just make us all proud. Make Jason proud.”

In the years he corresponded with Musser and Duffey, Carney had never heard from Gibson’s parents.

He did send a letter to Gibson’s mother at one point, but he never got a response back. He says after re-reading it countless times, it feels too still, too formal, and not personal at all. He added he doesn’t blame Michelle Gibson for not forgiving him, but he’d like the opportunity to one day apologize to her, face-to-face.

“I’ve always wanted to tell her I’m sorry and I’ve read her letter countless times,” Carney said, his breath catching on the last word, “I’m sorry.”

This article originally appeared on Sarasota Herald-Tribune: Forgiveness gives incarcerated Florida man new beginning of hope