Forgiveness helps unload those heavy mental rocks, doesn’t stand in the way of justice

Folks who’ve held a grudge over a wrong, mentally replayed a hurtful incident over and over or struggled to move past tragedy have access to a tool that could free them from the pain — and the person who inflicted it.

The REACH forgiveness workbook, developed by psychologist Everett Worthington, is designed to provide a starting point and directions to navigate the path to forgiving someone. It’s free, takes between two and three hours and can be used almost anywhere in the world by virtually anyone who has something they would like to let go.

Forgiving someone is not the same as excusing or reconciling, said Tyler J. VanderWeele, director of the Human Flourishing Program and co-director of the Initiative on Health, Spirituality, and Religion at Harvard University — and an advocate of the workbook’s process.

Forgiving does not mean someone doesn’t seek justice for a wrong, either, he said.

On the “Human Flourishing” blog hosted by Psychology Today, he wrote that forgiveness can set someone free. From the hurt. From replaying the painful event over and over. And even from the offender.

Why forgive

“Exquisitely important” is how Andrew Serazin, president of the Templeton World Charity Foundation, describes forgiveness, calling it an area of human interest and human need.

He told the Deseret News that mammals are hardwired for revenge and shame and guilt. “Punishment and negative feelings toward an offender” were effective when societies were small, he said.

But it’s not a tenable path forward in the modern world. “In order to cooperate across diverse groups, long distances and long time frames, we humans needed a strategy to overcome a cycle of vengeance, guilt and shame. In that sense, forgiveness is a miracle because it is a behavioral strategy that breaks us out of that cycle,” Serazin said.

The benefits are impressive.

According to Johns Hopkins Medicine, research shows that the act of forgiving — it takes genuine, internalized action — reduces the risk of heart attack, lowers cholesterol, improves sleep quality and dials down blood pressure, pain and anxiety levels. It counters depression and stress. And the impact of forgiveness keeps growing as people age.

Researchers and health practitioners have found that forgiveness lets one release anger and other negative emotions, replacing them with empathy, compassion and sometimes even affection.

Holding onto hurt or anger harms humans in ways known for years. A 2009 study in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, for instance, linked anger and hostility to a greater risk of heart disease and said those who already have cardiovascular problems and harbor those feelings tend to fare worse than those who can let grievances go.

The workbook itself lays out the case for forgiveness, noting that harboring anger increases the stress hormone cortisol in the body. It can cause digestive problems, mess with one’s immune system, interfere with sex drive and deplete memory, among other ill effects.

“Science has shown that forgiving, when practiced over time, makes people physically healthier, more psychologically adjusted, happier in relationships and more spiritually calm. But it takes time and effort,” the workbook says.

Worthington points out that forgiveness has two parts: Deciding to forgive improves relationships and spirituality, while emotional forgiveness improves mental and physical health, though the latter takes longer. For most, the emotional side is harder than simply deciding to do it, he said.

Empathy can flow both ways, VanderWeele said. “If something you say or do deeply hurts or offends another person, even if you believe you did nothing wrong, it can still be helpful to express sorrow for the other’s pain. In some cases, this itself might facilitate healing and might help the other person to forgive.”

A family’s tragedy

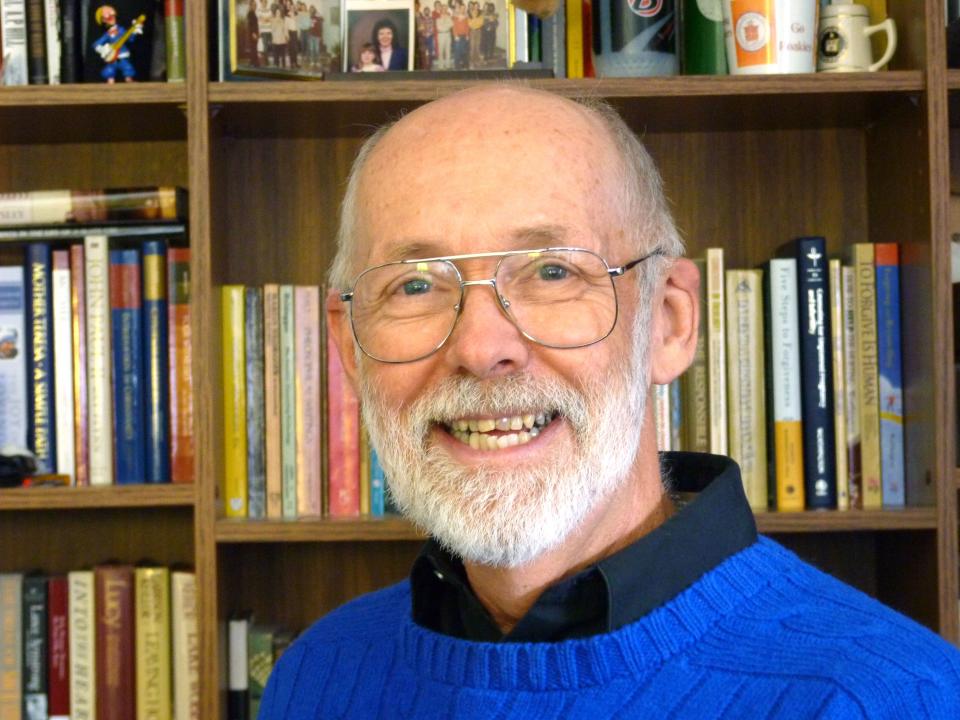

Worthington had been studying the power of forgiveness for at least six years when tragedy forced him to confront whether he could walk the talk he’d put forth in several books on forgiveness and hope and finding peace. He’s now written dozens of books on related subjects.

On New Year’s Day in 1996, his mother’s body was found in her home. She’d been murdered by an intruder, robbery the suspected motive. His younger brother, who’d been unable to reach his 77-year-old mom, had gone over and found her body.

Though police had a suspect, the young man was never charged and the case was never officially solved.

Still, Worthington and his brother and sister each decided separately that to honor their mother’s life, they would find a way to forgive the person who killed her.

It wasn’t the first time he’d made a hard decision and changed directions. Before he was a marriage counselor and professor, Worthington was a nuclear engineer with a master’s degree from MIT. As a naval officer, he found an aptitude and a liking for counseling so he changed course and studied psychology, which eventually led to his 40-year career as a couples counselor and a professor of psychology at Virginia Commonwealth University. There, he has become an internationally renowned expert in the field of forgiveness research.

Asked if talking about his family’s tragedy would make him feel bad, Worthington responded, “At this point, like many other things that happened to us in life, it’s something that is in the past. Of course, like everybody, I remember — and especially remember around the New Year’s holiday. But it does not really cause me great pain, just memories of her and the legacy she left in the lives of myself, my brother and my sister.”

Part of that legacy was the profound belief shared that their mother, Frances Worthington, would want them to forgive her killer.

His life’s goal, Worthington said earnestly, is to “promote forgiveness in every willing heart, home and homeland. I think (the workbook) is a way to make it possible for people who are willing to work on forgiveness anywhere.”

REACH forgiveness workbook

The idea of the workbook, which has had different iterations as Worthington worked to boil it down from about seven hours of evidence-based practice to being doable almost anywhere in the world in less than half that time, was “to help anyone who wants to forgive to be able to do so more efficiently and effectively,” he told the Deseret News. Most people aren’t sure how to start.

The workbook has been the subject of numerous randomized controlled trials that vet its effectiveness, he said.

“Pretty much anybody can do it,” said Worthington. “It introduces the topic and defines a working definition of forgiveness.”

VanderWeele said it was tested in “relatively high-conflict countries — Columbia, South Africa, Ukraine, Indonesia and Hong Kong.” People were randomly assigned to receive the workbook right away or had to wait a couple of weeks. Just before the delayed group got it, researchers measured forgiveness.

Per VanderWeele, those who got it right away showed more forgiveness than those who had to wait, although they, too, were seeking to forgive a hurt or wrong. The workbook-first group displayed less depressive symptoms and anxiety levels during the assessment and their sense of hope appeared more buoyant.

He wrote that using accepted human flourishing measures, researchers found “evidence it increased various aspects of flourishing: happiness, health, meaning, character, relationships and even a sense of financial security.”

A paper on the studies’ results is in the peer-review process, but researchers released a preprint of findings early because they are important. They hope people will start on their forgiveness journey right away.

In the workbook, people tackle one incident they want to forgive. Later, there’s a section with several other hurts they try to work through, “so they are applying those to different hurts in their lives,” said Worthington. “Hopefully, they don’t just get help with one hurt, but they learn a skill or improve their natural skills in forgiveness.”

The workbook name is an acronym Worthington came up with to describe the five steps involved in forgiving. Those are:

Recall the hurt.

Empathize with the person who caused it.

Altruistically forgive.

Commit to that forgiveness.

Hold onto the forgiveness when you doubt, which will likely happen.

Justice is a different issue

Forgiveness isn’t the only route to cope with injustice, Worthington said. “There are many good ways. But if people are willing, forgiveness is powerful.”

But forgiving — and Worthington, VanderWeele and other forgiveness experts emphasize this repeatedly — does not mean foregoing justice.

“Forgiveness and justice are actually in different realms,” Worthington said. “Forgiveness is something that happens internally. When my mother was murdered, I could forgive the young man that did that. But if he were to be caught and brought into the justice system, it wouldn’t matter whether I had forgiven. He would still have to face justice, which is societal.”

One’s sense of injustice — “the injustice gap” — hinges on how hard it is for one to deal with the feelings around it. “One of the things we try to let people know is they can mix and match these ways of dealing with injustice. They can go to God. They can appeal to God for divine justice. They can relinquish it to God. They can seek justice in the justice system. They can forebear, tolerate, accept, move on. However they can get the injustice they feel down, the lower it can get, the easier it is to forgive,” Worthington said.

Serazin said that most people say forgiving allows those who’ve been wronged to go through a formal process of justice in a more objective way — “a way that doesn’t cause continued hurt.” Those who hold onto negative thoughts and feelings, on the other hand, have a tendency to ruminate. “You just think about it over and over and every time you do that, it causes pain.”

He added, “Justice is about making sure there are appropriate consequences to things that happen without carrying this unforgiveness in the heart in a way that is ultimately taxing and draining for physical and mental health. Justice and forgiveness can work side by side.”

Having experienced the worst of human nature, Worthington nevertheless believes that “nothing, in principle, is unforgivable.” Practice, though, may be different. Forgiving can feel like trying to jump over a 20-foot fence, he said. “We just physically or by our nature or by our experience cannot get over that fence. That’s why I think it’s important for people to realize forgiveness doesn’t have to do all the heavy lifting.”

He emphasizes that forgiving someone does not have to lead to reconciliation. You can even forgive someone dead who has harmed you — reconciliation is impossible there.

“I can forgive someone and it still might not be desirable or prudent to reconcile with them. Reconciliation requires restoration of trust. If someone isn’t trustworthy, it would not be a good idea to reconcile, but I can still forgive.”

That lets one lay down tortuous memories and move on, he noted.

Adds Serazin, “to engage in strategies like visualization or perspective taking where you put yourself in someone’s position, or physical activity like giving a gift. Those are really important because they get the rest of the body to go along with the decision to forgive. Without that kind of twofold approach, the benefits aren’t as powerful.”

The Templeton World Charity Foundation has its own forgiveness initiative and resources, available online at Discoverforgiveness.org. So it was a no-brainer for the group to support a free downloadable workbook that’s readily available globally, Serazin said. The foundation provided a grant to fund a trial to see if it worked.

“We were very pleased and honored to be able to fund something global in scope that can meet people where they are, whether they have access to therapists or other resources or whether they are by themselves,” Serazin said.

“It’s surprising that a two-hour intervention can make a difference on really deep-seated things like anxiety and depression,” he said of the study results. “Our support for this research is part of a broader multimillion-dollar effort about raising the profile and practice of forgiveness.”

You can download the workbook here.