'Forgotten' ancestor found and honored in Utica's Forest Hill Cemetery

Nancy West, 64, of Rocky Mount, North Carolina, has relatives all over the Utica area.

Some are in Crown Hill Cemetery and Sunset Hill Cemetery in Clinton and some in the Masonic Care Community Cemetery, St. Mary’s Cemetery and Forest Hills Cemetery in Utica.

But during a trip to Utica in the summer of 2021 to trace farther back along her three family lines with roots in Oneida County, West discovered a “lost” ancestor, a great-great-great-grandfather without a known grave.

This is the story of how John Jones got lost when Utica needed a new playground. It’s the story of how his descendant found him and honored his memory. And it’s the story, too, of all the nameless late Uticans who remain lost, lying near Jones in unmarked graves.

“All these people have basically been forgotten,” West said. “So it’s really poignant for me that I was able to re-establish a permanent marker for the memory of at least one of them. So he’s not forgotten now.”

Finding a connection

When West found out that John Jones worked as the foreman of a livery stable in Utica, she felt a connection. West’s maternal grandfather had joined the cavalry and ridden out of Union Station in Utica to join the Mexican Punitive Expedition of 1916 and 1917.

Another ancestor from Scotland served in the Royal Horse Artillery during the Indian Rebellion of 1857.

And West herself, who was born in Rome, spent eight years in Camden and graduated from Utica College, had learned to ride on the Clinton farm where her uncle raised Morgans (a breed of horse) and lived in Saratoga Springs as a teen.

When her uncle died in 2015, she inherited, and still has, one of his horses, Harvey’s Golden Viking, or Goldie for short.

Her ancestor, she realized, must have done the same thing every day that she does — cleaning up a horse’s stall.

“It just means something,” she said.

And Jones hadn’t just worked at a livery stable, he’d worked at the city’s largest, which was owned by John Butterfield, Utica’s 24th mayor. “That stable was massive,” West exclaimed. “It had 80 horses in what is now the block in between Main Street, Broad Street, First Street and John Street.”

Butterfield ran a stagecoach company and became a co-founder of the American Express Co. And, in 1858, he established the first regular overland mail delivery service between St. Louis and San Francisco.

Jones’ and Butterfield’s stories have now helped to shape West’s. The newspaper reporter, who has also taught English, worked in radio and TV news, and worked as an electronics repair technician, has now taken on a new job, writing a historical fiction novel about a family running a livery stable.

West wanted to pay her respects to her great-great-great-grandpa, but didn’t know where he was buried.

The search

So, she headed to the Oneida County History Center.

“It’s not fun,” she remarked, “doing genealogy research on a person named John Jones, especially In Utica where they’re all from Wales.”

She discovered that Jones had been buried in Potter’s Field Cemetery, near today’s Utica Memorial Auditorium, which was named for Mr. Potter, who owned the field. But the cemetery was gone.

“The whole cemetery had been dug up and moved in 1916 in order to put a playground there,” West said she discovered.

As West hunted more, she discovered that many of the bodies had been moved to Forest Hill Cemetery, which opened in 1850 and contains the graves of many of the area’s most prominent citizens.

West already knew that Jones’ son, John K. Jones, a railroad engineer who died in 1910, is buried in Forest Hill in a family plot shared by five other Joneses, all of whom died after John K., including another John, this one with the middle initial “P.” John K.’s brother Charles, who died in the Civil War, is also buried in Forest Hills, West discovered.

She asked the Forest Hill staff if they knew where the senior Jones would have been buried. To find the grave, office manager Amanda Kidder had to read through a handwritten book listing the names of everyone who had been brought from Potter’s Field to Forest Hill. None of the information was ever recorded in Forest Hill’s official book of burials (an omission that would not occur today, staff stressed).

A search for the name John Jones in Forest Hill on the website FindAGrave.com turned up 96 records.

But, Kidder found the name and the approximate location — grave 64 in tier 16 of the cemetery with his remains in box 4319 and possibly 4320 as well. The tiers in the cemetery used to be the areas where burials paid for by the Oneida County Department of Social Services took place, Kidder explained. Those burials still take place, but in a different section.

It’s impossible to know exactly where any one person from Potter’s Field lies, Assistant Superintendent Kyle Waterman said. And although staff believe they’ve identified an area where Jones and some of the others from Potter’s Field are buried, they can’t be completely sure they’re right, he said.

That spot is a grassy area on one side of the cemetery, nestled against the woods that edge the Forest Hill. It’s an area marked “public grounds” on the plans, the only area in sight without any grave markers although it’s surrounded by crowded tombstones. And it offers a view of some of the area’s more ornate statues and tombstones, testaments to the wealth and prominence of those buried below.

How it happened

Two newspaper clippings among the cemetery’s records, without a specific date or newspaper name attached, explain some of the history of that grassy patch of earth where bones apparently rest, some identified in the log book and some presumably completely unknown.

Potter’s Field Cemetery was officially named City Cemetery and it used to be the primary place for burials in Utica, according to the articles. But over time, more cemeteries opened farther away from the oldest section of the city and Potter’s Field fell into “neglect and decay.”

Residents started talking about putting a park on the site. In 1900, the city bought a portion of the cemetery south of Water Street, moved 54 bodies to Forest Hill and built Potter’s school on the site. The city paid the cemetery $27 a year for upkeep of those graves.

A group of women then pushed for a playground to be built on the rest of the cemetery. So in 1916, the city applied to the state for permission to move the rest of the bodies and to purchase the land. Permission was granted and the city disinterred 4,764 bodies, 3,826 of them unknown.

The city agreed to pay the cemetery 50 cents per grave each year for upkeep, an amount expected to total $982.50 annually. Mr. Dickinson, Common Council president at the time, objected to the expense, arguing that the city should not be saddled with it “from now to eternity.”

He got his wish. Waterman said the city does not pay the cemetery for upkeep and he has no idea how long the payments lasted or whether they ever even started.

And that is how John Jones ended up in an unmarked grave in Forest Hill Cemetery, a stone’s throw or two from where his son had been buried six years earlier.

One lone marker

After some research, cemetery staff assigned West a corner of the “public lands” empty space for a marker honoring John Jones. She ordered a flat marker on Ebay, needing something light enough that she could afford to ship it.

West chose a marker that’s actually designed for a horse to honor her connection with her three-times-great-grandfather.

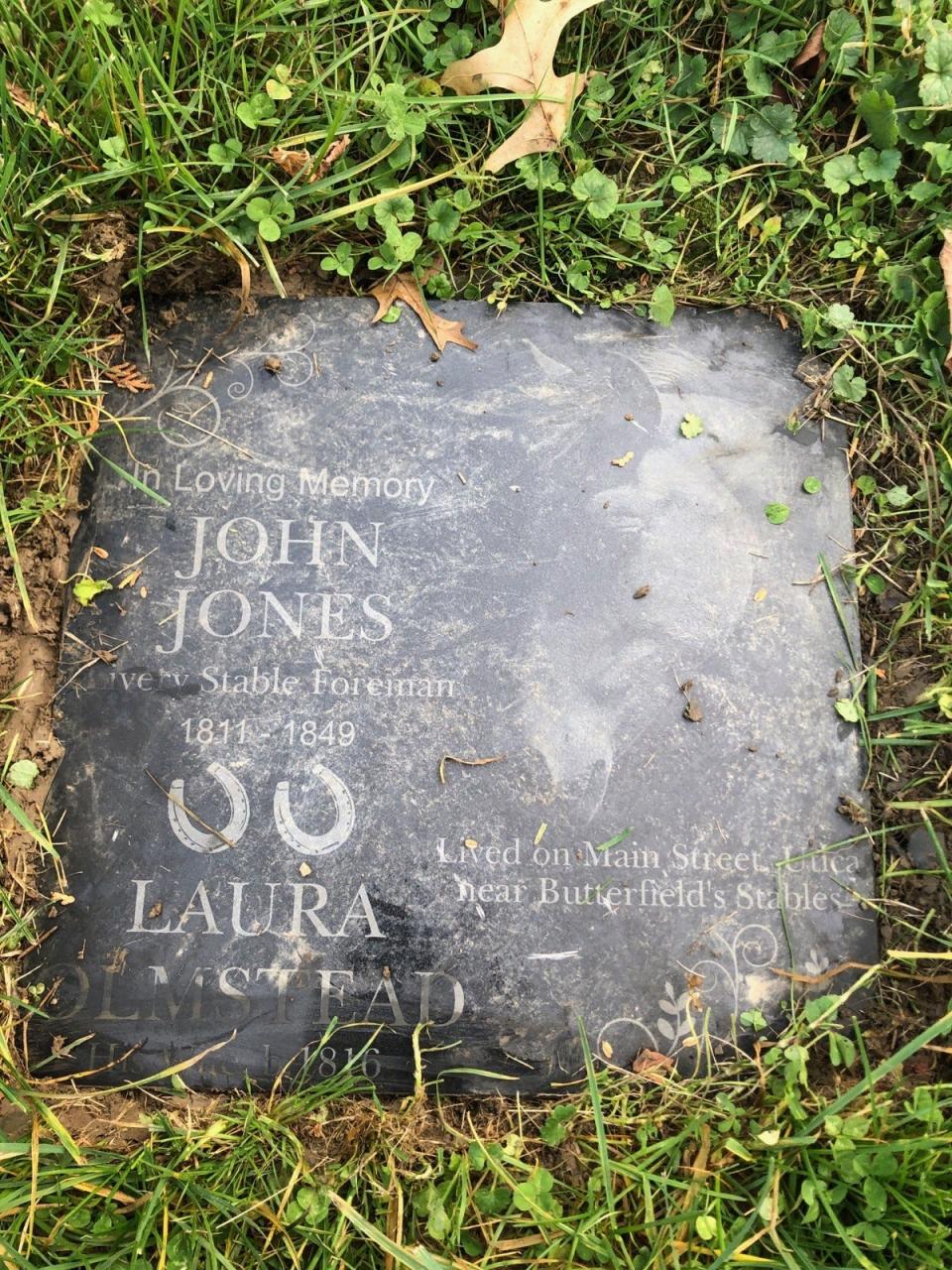

It’s decorated with an engraved picture of two horseshoes and a larger picture of a horse’s head. It reads: “In loving memory/John Jones/livery stable foreman/1811-1849/ Laura Olmstead/his wife-b. 1816." His wife, however, is not buried with him.

It remains the only marker in that section, honoring someone buried in Potter’s Field.

West hasn’t been back to Utica since the marker was installed. She thinks she might make it this fall.

But she feels better, she said, knowing that John Jones has been claimed and that he will be remembered.

This article originally appeared on Observer-Dispatch: North Carolina woman with Utica roots finds ancestor's grave