'Forgotten': Kentuckians still stuck in campers and sheds 5 months after flooding

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

LITTCARR, Ky. — When cars aren’t roaring past, the only noise audible from Donna Roark’s driveway is water dripping from a culvert across the road.

One night in late July, Roark awoke to find floodwater shooting out of it like a firehose. It was a miracle her home survived, she said.

For the past five months, Roark has helped survivors who were less fortunate rebuild and restock. She’s watched FEMA processes drudge on for months, outside help dwindle, the temperatures drop while safe, warm housing remained scarce.

Despite persistent, pressing needs, leaders didn’t appear to have a game plan for now or the future. A region seemingly left out to dry.

So, when Gov. Andy Beshear arrived just a few miles up the road Tuesday and announced a vision for long-term recovery, Roark was happy — to an extent.

“It’s great that our officials have A LONG TERM Plan!” she wrote in a message. “But these people needed a plan months ago and look where they still are.”

An untold number of Eastern Kentucky residents — perhaps thousands — are still displaced or living in inadequate housing five months after flash flooding tore through the area. Some have even had to live in tents.

While Beshear’s announcement of a 75-acre space with housing, senior living and a school reignited some hope in the region, survivors and their advocates remain concerned about the immediate needs.

“If we can't solve this quickly ... they'll leave and they'll never come back,” said state Sen. Brandon Smith, a Republican who represents much of the area. “And that will be, to me, the beginning of the end of Appalachia as the way I know it.”

Barrier after barrier

When the floodwaters tore through a 13-county region of southeastern Kentucky in July, they took more than 40 lives and hundreds of homes with them.

The Foundation for Appalachian Kentucky, a Hazard-based nonprofit, said a month after the floods 1,749 homes were destroyed. Another 4,057 were damaged.

After the storm, survivors faced barrier after barrier to finding temporary housing and the resources they needed to rebuild.

FEMA’s handling of survivors’ aid applications quickly drew criticism. The process was too hard to navigate, many said, and was rife with rejection letters.

“My people are insulted with the offers they’re getting,” state Rep. Angie Hatton, D-Whitesburg, said during an August special session called to address the issue.

FEMA made a series of changes to better help disaster survivors, a spokesperson said, including calling aid applicants directly to work their claims. Nearly 2,300 otherwise ineligible applications got approved through the process, with awards totaling $23.5 million.

The agency also trained staff to check documents when they inspect homes, rather than requiring survivors to send them in separately. It expanded how survivors can prove they own or live on a property - important in a region where it is common for a home or land to be passed down through generations without the legal paperwork keeping up.

More than three-fifths of Eastern Kentucky applicants have been found eligible for some type of assistance, a FEMA spokesperson said - up from the 30% average eligibility rate agency-wide over the past five years. Eastern Kentucky's average FEMA award is $10,796 - more than four times higher than the national average.

Still, the offers have not been enough for many to rebuild and several survivors are still working through the lengthy appeals process.

And millions of dollars raised by a few well-publicized donation drives have yet to make it to many survivors. The Team Kentucky disaster relief fund for Eastern Kentucky has raised more than $12.6 million since July, with Beshear recently promising $500 checks for every person who received a cent from FEMA. It is unclear when survivors will receive their checks.

"Where's the money?" Roark questioned.

State lawmakers did not provide dedicated housing funding in a $213 million relief package for the region during the special session, instead leaving housing advocates to compete against school districts and local governments for the money.

Travel trailers were — and continue to be — the state’s main temporary housing solution. More than 300 travel trailers are spread across the area, but the figure is nowhere near enough to cover the thousands of people who said in their FEMA applications that they needed immediate shelter.

Getting a trailer previously required victims to leave their properties to be at a state park or campground miles away — something unappealing to some. As of Thursday, there were three trailers on private sites.

When asked who helped them the most, many survivors pointed to people like local aid groups and nonprofits — not authorities specifically tasked with disaster aid and recovery.

“Why did those people rise to the call and go above and beyond for free,” Smith said. “And then the people that we pay, that represent us and these emergency agencies, show up and — their actions will ring through that area for a long time.”

Smith thinks FEMA should be investigated for its response in Eastern Kentucky. Stopping short of agreeing with Smith, Beshear said in early December that FEMA needs reform.

Eastern Kentucky has seen some of the highest average payouts and approval rates for FEMA claims, Beshear said. And yet it hasn’t been enough — signaling FEMA’s response is not just a problem here, he said, but everywhere.

The housing crisis

The region faced an affordable housing crisis before the flood, advocates and lawmakers have said. But losing so many homes to the floods made things worse: When many survivors went searching for temporary housing, there was little to be had.

Scott McReynolds, who leads the Housing Development Alliance, a Hazard-based nonprofit focused on affordable housing, said “it’s hard to quantify” how many flood survivors are displaced or living in subpar homes.

Around 700 people are living in travel trailers or in rooms in state parks, according to the governor’s office.

“Then you get all the other folks,” McReynolds said.

Many survivors have been “toughing it out” since the flooding, McReynolds said. They may be living in old campers or makeshift homes in sheds or storage units — quick fixes found amid desperation.

“Now that it is getting a lot colder,” McReynolds said, living in those spaces is “getting a lot harder.”

Without a clear plan for housing, extra financial aid or more intermediate housing options, survivors are left to make do.

Roark said she knows of one family whose home was flooded and has mold growing under the floor, causing it to buckle and break away from the walls. They’ve needed to stuff clothes into the cracks to keep warm.

The family won’t tell their landlord about it because they’re afraid of getting kicked out with nowhere to go, she said.

“A lot of people are afraid of that, so they’d rather take the chance on living in mold than to be on the streets,” Roark said.

Others are fixing their properties as best they can be given limited resources, McReynolds said. That frequently lands them in less-than-ideal situations.

After their home washed away, one couple is trying to build a new home in the same spot, even though the area is likely to flood again, McReynolds shared.

If McReynolds knew what state and federal authorities would give survivors, he said, housing advocates could make a plan to rebuild and present a stronger alternative to them.

“They’re doing what they can to have a home,” McReynolds said in November. “It’s just a shame to see people spending money — their resources — on inadequate solutions because they don’t have hope.”

The bridge is out

Like many other survivors, Kasie and Ian Hall are in limbo after talking to authorities.

“Everyone’s telling us something different,” Kasie explained.

Outside of two doctor’s appointments, the couple hasn’t left their Pippa Passes home since late July.

Their ranch-style home, which sits high on a hillside, didn’t see serious flood damage. But the floodwaters that tore through Caney Creek were so strong, the decades-old bridge connecting their home to the road crumbled.

They’re far from alone: on top of housing struggles, at least a few dozen properties saw bridges and similar transportation infrastructure damage.

Having a bridge out could potentially lead to legal problems on top of the logistical ones, said Jenn Bell, an advocate working in Eastern Kentucky. If it prevents children from being able to get to school, Bell explained, that could mean problems for their parents.

The Halls' bridge is estimated to cost $100,000 to $200,000 to repair — a larger project than some of the smaller bridges wiped out elsewhere. Kasie feels as if the problem is “being swept under the rug so (authorities) don’t have to fund it.”

After the couple felt some progress was being made, they learned the state wanted a rescope of the project — which Kasie felt meant they were back at square one.

An olive branch

Roark and a few advocates in other counties recently had a multi-hour phone call with someone from the governor’s office, she said.

“I didn’t know it was that bad,” she remembers the Beshear official saying.

Misty Skaggs, an advocate who runs EKY Mutual Aid and was on the call, retorted, “‘'Well, you'd have to live under a rock to know it's not that bad.’

“Because people are hollering, ‘We need help’ on social media. They're hollering all over that they need help. And nobody's helping.”

Roark is one of the helpers. A roadside tent offering donated items to survivors grew into a two-car garage she's dubbed "The People's Building."

The space is organized but stuffed. Racks of clothes — the only donation she doesn’t need is clothing, she quips — line the walls. Tables of toys, stocking stuffers, dishware, cups covered in confetti take up the middle of the room, with boxes of surplus items underneath. Massive battered cardboard boxes hold bed linens and pillows.

“We are not getting any help from the county, from the officials,” Roark said. “People need to keep donating to this building or to someone so these people can still get what they need.”

Flood survivor Tina Miller, who stopped by Roark’s to pick up a few things, scoffed when asked about FEMA.

“FEMA is a joke,” she said.

She remembers watching the waters pick up her little girl’s dresser — along with many other belongings — and mercilessly take it all away. FEMA gave her $500.

Do you feel forgotten, Roark asked Miller.

“Forgotten,” Miller replied, before adding: “Mistreated.”

Then, after weeks of hinting at land purchases in hard-hit counties and a permanent housing plan, Beshear on Tuesday shared “a great Christmas present” for the region.

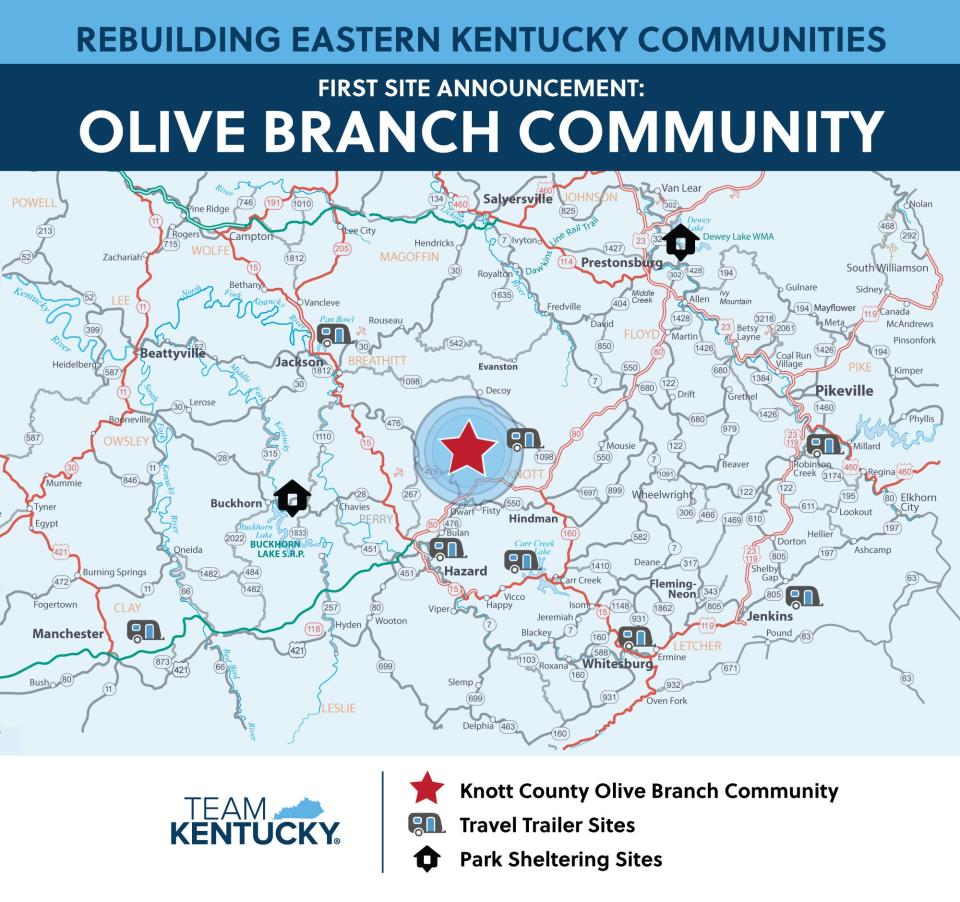

The state will break ground in early 2023 on a 75-acre site near the Knott-Perry county line on what it hopes will be the first of several new communities in flood-ravaged areas.

A concept of the space featured various levels of housing, a senior living complex and an elementary school. New infrastructure, including roads and a water treatment facility, are also included.

Tammy Adams, the daughter of coal and banking businessman Elmer Whitaker, and her husband, Shawn, donated the land. They suggested naming the space the Olive Branch Community — a nod to Noah’s Ark, where an olive branch signaled that flood waters had receded.

It is unclear when the space will be ready for survivors to move in. Beshear said Thursday that the site is being tested to ensure it is safe to build on, and he's confident it will be. After that, the timeline will be largely dictated by how long it takes to build the necessary infrastructure, he said.

There was some short-term housing hope, though.

The Foundation for Appalachian Kentucky is getting enough money to help around 80 families make repairs to their homes. HDA is getting $600,000 to construct eight new homes in the region — adding to a few other small rebuild projects already in the works.

McReynolds estimated the region will ultimately need at least 2,300 new homes, costing at least $600 million.

Having a heart

Kentucky’s 2023 legislative session starts Jan. 3, offering a chance for lawmakers to help survivors while long-term housing is being created.

Adrienne Bush, who leads the Homeless and Housing Coalition of Kentucky, called August's special session “kind of a missed opportunity.”

With more federal recovery dollars possible but not an immediate reality, Bush said there’s a “significant gap of both time and money where the state legislature could play a critical role in helping folks rebuild their lives.”

A coalition of 28 groups from across the state want lawmakers to create a flexible fund designed to tackle affordable housing issues following emergencies called the Affordable Housing Emergency Action Recovery Trust Fund — AHEART.

Under the proposal, lawmakers would put $150 million in the fund during the 2023 legislative session. And then in 2024, lawmakers would allocate another $190 million - $150 million for AHEART and $40 million for the Affordable Housing Trust Fund, a separate pot of money to address more long-term projects.

But the plan would require legislators to open state coffers in a nonbudget year — an idea a few top Republicans, who control both chambers of the legislature, have already bristled at.

Smith understands. “For every one good thing you want to put in the budget, you may have 50 other people that have pork barrel spending they want to stick in,” he said.

Smith said he is talking with others to see what housing policies may be in the works and how he can best fit into them.

“I'm aware of the fact that I'm not the only one that cares about housing,” he said.

Smith envisions building not just new homes, but ones where everything will be brought up to code with adequate heating and sewer systems. The goal: creating homes that will be passed down through generations.

“Obviously, I'm not going to quit on it,” he said.

Back in Knott County, Roark continues to open her donation center and share social media posts about items she and others have, should someone need them.

She vows to be there until the last survivor doesn’t need a thing.

Reach Olivia Krauth at okrauth@courierjournal.com and on Twitter at @oliviakrauth.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: 'Forgotten': Kentuckians still stuck in campers and sheds 5 months after flooding