The forgotten woman of German expressionism

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In a pretty little town called Murnau, in the foothills of the Bavarian Alps, there is a pretty little house that changed the course of modern art. It was here, in 1911, that a group of German and Russian artists assembled the Blaue Reiter Almanac. This book of essays and illustrations became a manifesto for a new generation of artists, who painted not only what they saw but also what they felt. These Blaue Reiter artists revolutionised European art, and the men among them became famous, most notably Wassily Kandinsky. But the Blaue Reiter wasn’t just a group of male artists. It included several female artists too, most notably Gabriele Münter. Münter was a brilliant artist, just as good as Kandinsky. So why is she hardly known about outside her native Germany, while Kandinsky is renowned worldwide?

Münter was no bit-part player in the Blaue Reiter. She was a prolific painter, with an evocative, innovative style. However, she was also Kandinsky’s lover, and while Kandinsky became a household name, Münter has gone down in history as his girlfriend, rather than an artist in her own right. It’s an injustice many female artists have had to face, but for her it seems especially unfair. Münter was a major influence on Kandinsky, and on the other Blaue Reiter artists too. She helped to fund the Almanac. She owned the house where it all happened. Without her creative input, it’s quite possible the Blaue Reiter never would have got off the ground, and the history of modern art would have taken an entirely different course.

Gabriele Münter was born in Berlin in 1877. Her family was comfortably off (her father was a dental surgeon). By the time she came of age both her parents had died, leaving her a generous private income. In 1898, at the age of 21, she set off for the United States with her sister. She spent two years travelling around the US, pursuing her passion for photography. This epic trip was a demonstration of her independent spirit, and her artistic talent: 120 years later these striking photographs still look astonishingly modern – a world away from the staid and stilted photography of that era.

Münter returned to Germany in 1900, determined to become a painter. She went to Munich which, then as now, was one of the artistic centres of Europe. The Kunstakademie, Munich’s official art school, didn’t admit women, but there were several unofficial art schools that did. Münter attended various classes and in 1901 she ended up at an ad-hoc art school called The Phalanx, run by a charismatic Russian émigré called Wassily Kandinsky.

Kandinsky had come to Munich five years before, aged 30, to train as an artist at the Kunstakademie, abandoning a career as a lawyer in his native Russia. Despite his relative inexperience as an artist (or perhaps, in part, because of it) Münter found him an inspiring teacher, and their professional relationship soon developed into something deeper. In 1902, he invited her to join him on a painting trip to Kochel, an attractive lakeside town near Murnau, south of Munich. By the time they returned to Munich, they were lovers.

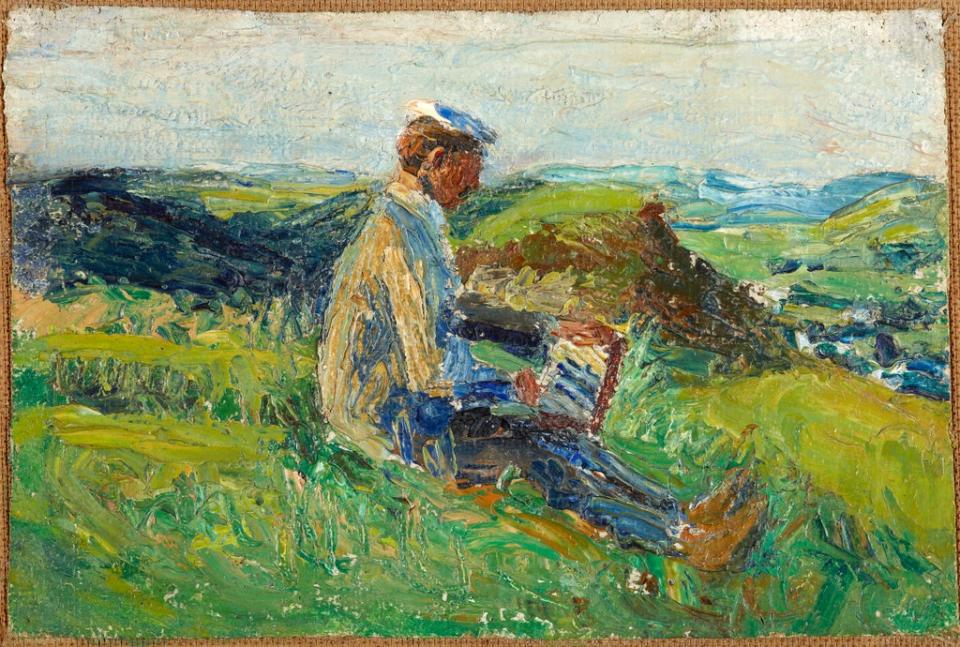

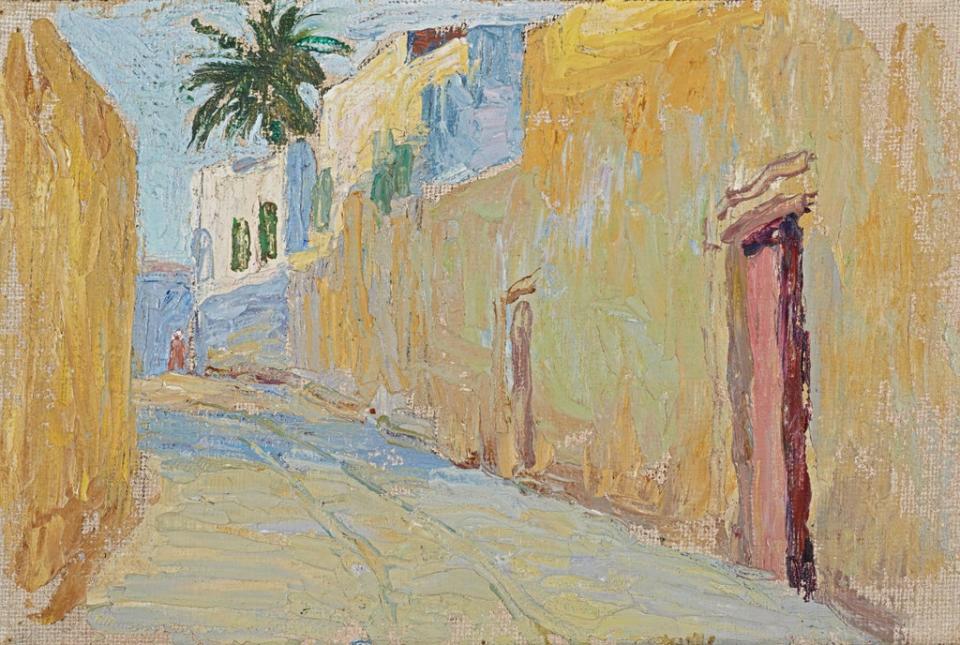

Kandinsky was already married, living with his Russian wife in Munich, but Münter and Kandinsky were inseparable and in 1904 they hit the road – to pursue their shared passion for painting, and to escape Kandinsky’s jilted wife. They were away for four years. They travelled all over Europe, and spent several months in Tunisia. The paintings they did en route form the basis of an absorbing new exhibition called Under Open Skies at Munich’s Lenbachhaus museum. Kandinsky’s paintings are more accomplished (he was 11 years older, and he’d had a far more comprehensive artistic training) yet although Münter’s paintings are simpler, they’re just as powerful. “Ever more intensely, I perceived the clarity and simplicity of this world,” she recalled, describing the moment when it finally all came together. She was no longer Kandinsky’s pupil. Her style was entirely her own.

In 1908, Münter and Kandinsky returned to Bavaria and settled in Murnau. It was an inspired choice. Removed from the attractions and distractions of Munich, they could focus on their work – and there was a wealth of things to paint. For Münter, it was love at first sight. “I was instantly enchanted,” she remembered. “Nowhere else had I seen such an abundance of fine views.” Virtually untouched by the vicissitudes of the last century, Murnau and its environs still look much the same. The town is picturesque, the light is stunning and the lakes and mountains are sublime. Seen in a sterile gallery, their vivid landscapes seem rather fanciful, but when you see the views they painted, you realise they’re actually remarkably true to life.

He’d promised to marry her. She’d given him the best years of her life. She was in her mid-forties now, too old to bear any children

In 1909, Münter bought a house here, where they could live together as man and wife. Rural and traditional, their new home felt far removed from Munich but it was only an hour or so away by train, and many of their fellow artists came to stay. Their close friends Alexej von Jawlensky and Marianne von Werefkin were frequent visitors. Franz Marc and his wife Maria settled in Kochel, not far away. Meeting up in Münter’s house, they shared ideas and spurred each other on. They gave their ensemble the enigmatic title Der Blaue Reiter – the Blue Rider (this part of Bavaria is known as Das Blaue Land on account of its blue lakes, blue skies and blue horizons, and horses were one of Marc’s favourite motifs). Marc, Kandinsky and Jawlensky are usually cited as the main founders of the Blaue Reiter, but if you dig deeper you soon discover their female partners played an equally important part.

Like Kandinsky, Jawlensky and Von Werefkin were Russians, and locals soon took to calling Münter’s house “The Russian House.” No matter that Münter was German. Her lifestyle and appearance were just as foreign. She rode a bicycle – a most unladylike occupation. She went out in all weathers, painting en plein air. Murnau was an old-fashioned farming community, with old-fashioned ideas about the role of women in society, and a deep attachment to the conservative values of the Catholic church. The new railway had put Murnau within easy reach of Munich, but culturally the big city was still a long way away. For Kandinsky, a married man, to be living with Münter, an unmarried woman, was seen as scandalous (Jawlensky and Von Werefkin were also unmarried, yet they also lived together as man and wife).

Most emancipated women would have beat a hasty retreat back to Munich, but Münter was made of sterner stuff. She became fascinated by local folk culture, in particular a style of painting known as “reverse glass painting”, in which bright blocks of colour framed by bold black outlines are painted directly on to the backs of panes of glass. The subjects of these “reverse glass paintings” were generally religious, but Münter applied this rudimentary style to her own painting, and the results were riveting. Kandinsky toyed with a similar style for a while, but although his work was previously regarded as having influenced hers, it now seems just as likely it was the other way around. “They got something from each other that they both needed,” explains Sarah Henn, curator of Under Open Skies.

Münter and Kandinsky lived together in Murnau until 1914, and during these golden years her reputation blossomed. She exhibited all over Germany, and as far afield as Paris, Moscow and Budapest. But then Germany and Russia went to war, and everything changed. Kandinsky and his fellow Russians, Jawlensky and Von Werefkin, were now all enemy aliens, ordered to leave the country within 24 hours. They fled to neutral Switzerland, and Münter went with them. In 1915, Kandinsky returned to Russia, to put his affairs in order. Münter went to neutral Sweden. He told her he’d join her there.

Kandinsky did join her eventually, but only for a few months. Then he went back to Russia, leaving her alone in Stockholm. In 1917 he broke off all contact with her. It took her several years to find out why. In 1920, she returned to Germany. It was there, in 1921, that she discovered that Kandinsky, having divorced his first wife, had been married to another woman since 1917. He was in his fifties, his new wife was in her twenties. Münter was heartbroken. He’d promised to marry her. She’d given him the best years of her life. She was in her mid-forties now, too old to bear any children. And now he’d married a woman who was young enough to be her daughter.

Their relationship ended in an ugly legal dispute over the paintings he’d left in Murnau. He wanted them back. She said she had a right to keep them, as recompense for breaking his promise to marry her. In the end they reached a compromise, and some of his paintings were returned to him. Although he was now back in Germany, working as a teacher at the Bauhaus, he never returned to Munich, or Murnau, and he never saw her again.

For Münter, the 1920s was a listless decade. She suffered from depression. She didn’t do much painting. She lived in Berlin for a while, and then in Paris, but she didn’t put down any roots. But then in 1930 she formed a relationship with Johannes Eichner, a German art historian. In 1931 she returned to her old house in Murnau, and after a few years Eichner joined her there. Her work picked up. After 20 years of anguish, she was happy again.

Personally, Münter was content once more, but the world beyond her doorstep was growing ever darker. After Hitler came to power, in 1933, Germany changed utterly, and as his grip on power tightened liberals like Münter had to learn to keep their heads down. Along with several other Blaue Reiter artists, Kandinsky’s paintings were condemned as degenerate, seized from public galleries, and banned from public view. Mercifully, Münter didn’t suffer the same fate (official decisions about which artists were “degenerate” and which ones weren’t were notoriously inconsistent) but as the cultural climate became more and more rabid and reactionary, and any art that was even vaguely modernist was denounced as unpatriotic, it became increasingly difficult for her to sell or even show her work.

The war years were particularly tough. Nobody had money to spend on art (she traded artworks for food) and as defeat drew near, the paranoia of the Third Reich reached fever pitch. The police raided her house, looking for “degenerate” artworks. Thankfully, they didn’t find any, but if they’d found the enormous stash of forbidden Blaue Reiter pictures in her cellar, she would have been in deep trouble. People had been shot for less.

Yet Murnau was one of the better places for a German to spend the Second World War. The town escaped the carpet bombing that devastated so much of Germany. In 1945 it fell to American troops rather than the rapacious Red Army. Bavaria ended up in the free Federal Republic of West Germany, rather than the Soviet controlled East German “Democratic” Republic. In 1949 Münter was honoured with an exhibition at the Haus der Kunst in Munich, a gallery built to house Hitler’s favourite artists, now given over to the artists he’d persecuted. However, outside Germany she remained a footnote in the history of the Blaue Reiter, dismissed as Kandinsky’s mere muse. Although Kandinsky had died in 1944, he was now more famous than ever, and the more famous he became, the more she shrank into his shadow.

Why did Kandinsky eclipse her? Partly on account of his abstract paintings, which were truly groundbreaking, but mainly because he was allowed to write his own myth. In 1936, to mark what would have been Franz Marc’s 50th birthday (Marc had died in 1916, a soldier on the Western Front), Kandinsky was invited to write a history of the Blaue Reiter. His history was terribly biased (he highlighted his own work, while Münter, Jawlensky and Von Werefkin weren’t even mentioned) but as the only member of the group to write a detailed account, his memoir became a major source for all sorts of art historians.

Kandinsky’s artistic development, from Impressionism to Expressionism to abstraction, fits far more easily into the chronological story of 20th-century art. Münter’s style was more idiosyncratic. Her development wasn’t so straightforward. “Her pictures always really touch me,” says Sarah Henn. “Her works have this way of drawing me in emotionally.” Her art is warm and tender. She stood one step apart from the artists of her time.

In 1957, to mark her 80th birthday, Münter bequeathed her precious collection of Blaue Reiter paintings to Munich’s Lenbachhaus, a collection that had remained hidden in her house in Murnau for 40 years. This spectacular bequest caused a sensation in the art world, transforming the Lenbachhaus into a world-class gallery, with the world’s largest Blaue Reiter collection, but the international media focused on the lost Kandinskys she’d revealed, after all these years, rather than on her own paintings. Would she ever escape Kandinsky’s shadow? Not in her own lifetime. When she died, in 1962, she was mourned in Germany, but the wider world didn’t care.

Yet in the last 10 or 20 years, something rather wonderful has happened. While other artists fade away, eclipsed by contemporary fads and fashions, Münter’s reputation has grown and grown. The Lenbachhaus has played a leading role, mounting numerous exhibitions, and their current show, Under Open Skies, feels like a landmark in this process. It’s about Münter and Kandinsky, but they’re presented here as equal partners. And on the strength of the art alone, I can confirm she fully deserves joint billing.

If the ghost of Gabriele Münter lives on anywhere, it’s back at her old house in Murnau, where she lived for over half a century, until her death at the grand old age of 85. Sixty years on, this old house still feels full of her. Today it’s an evocative museum, full of her brightly painted furniture, and a fine selection of her paintings.

There’s an even bigger collection of her work in Murnau’s Schlossmuseum, a gallery in a medieval castle. There are some paintings by Kandinsky too, but Münter’s paintings enjoy equal prominence. A century since he left her, at last her art is being taken seriously. “All my paintings represent moments of my life – fleeting, virtual moments,” she explained. Here in Bavaria, it feels thrilling to see those fleeting moments come alive. “There’s so much material – so many amazing paintings, and diary entries and sketches,” says Henn. “There’s still so much more to discover.” For Münter, this is only the beginning.

For more information about art in Munich, visit www.muenchen.de. For more information about art in Murnau, and beyond, visit www.germany.travel. Under Open Skies is at the Lenbachhaus in Munich until 30 January 2022. www.lenbachhaus.de

Read More

The forgotten Pre-Raphaelite sisterhood

Elisabeth Frink: Sculptures dealing with timeless issues

Henry Scott Tuke: Pleasant escapism or iconic images of gay love?

Gustav Metzger is the most influential artist you’ve probably never heard of