Former deputies and a nurse charged in North Carolina jail inmate’s death

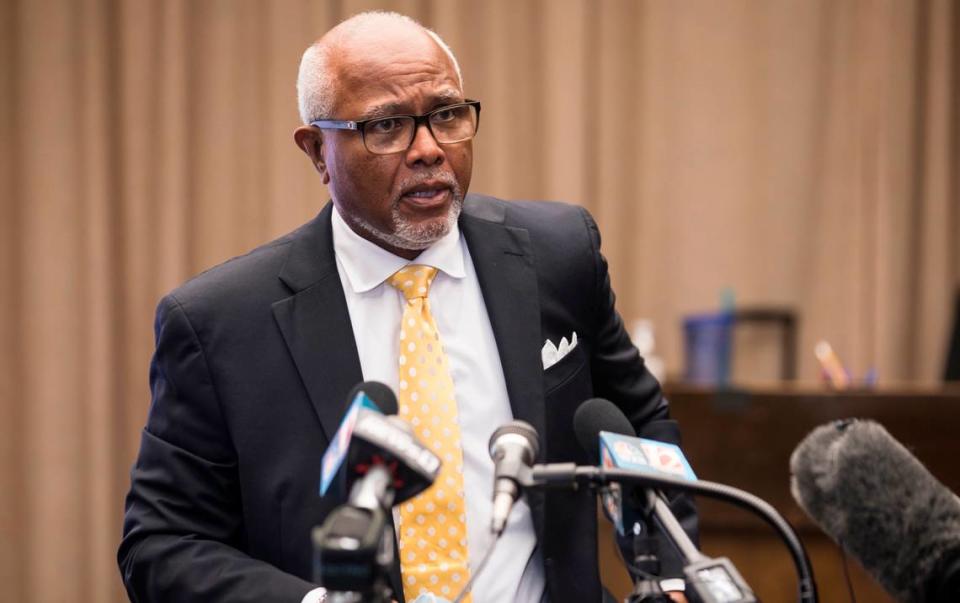

Five former sheriff’s deputies and a nurse face charges in the death of a 57-year-old Greensboro man, the Forsyth County district attorney announced in a news conference Wednesday, more than seven months after John Elliott Neville’s death.

Neville died in a hospital from a brain injury, District Attorney Jim O’Neill said, citing an autopsy report from the N.C. Office of the Chief Medical Examiner that has not been released to the public.

O’Neill said the injury was caused by deputies using prone restraint, a controversial technique to restrain an inmate. Neville went into cardiac arrest at the jail due to compressional and positional suffocation. A lack of blood flow to the brain led to the injury that ultimately killed him.

Neville, who is Black, repeatedly said “I can’t breathe,” while being held down, O’Neill said.

The six face charges of felony involuntary manslaughter.

Sheriff’s officials said last month that their employees had never faced any disciplinary action for what happened to Neville.

And up until Wednesday’s news conference there had never been a public announcement about Neville’s death.

The News & Observer filed a petition last month seeking the release of any videos that captured what happened to Neville at the jail. The hearing is scheduled for July 15.

Neville’s family, who joined O’Neill at the news conference, asked that the video of Neville’s death not be released until any cases go to trial.

Jail deaths

The news comes just months after the jail’s medical provider, Wellpath, settled a lawsuit with the family of Forsyth County inmate Stephen Antwan Patterson, who said he died because of neglect, according to the Winston-Salem Journal.

Despite not informing the public about Neville’s death, sheriff’s officials were quick to announce Tuesday morning the death in jail of 31-year-old Anthony Robert Giles, who they said left a suicide note.

Neville was among a record 46 inmates who died in North Carolina jails or in a hospital in 2019 after becoming infirm or injured, state Department of Health and Human Services records show. Those deaths include two inmates who were attacked by other inmates, law enforcement officials said.

DHHS officials found more than 40% of those deaths, including the two attacked inmates, involved supervision failures. DHHS didn’t investigate Neville’s death because Forsyth officials told them he wasn’t in custody when he died.

The North Carolina Sheriffs’ Association has sought to shut down new DHHS rules intended to improve the safety and supervision of inmates. A bill to do that in the state legislature was pulled from consideration just before a committee meeting and has yet to resurface. The rules take effect if lawmakers don’t act before the session ends.

In 2017, the N&O reported systemic problems regarding inmate supervision in a five-part series: Jailed to Death. The series also showed how some jails were not disclosing deaths to DHHS when an inmate died in the hospital. Lawmakers later passed a reform requiring disclosure of in-custody deaths at hospitals, but did not extend that requirement to out-of-custody deaths.

The News & Observer began asking questions about Neville after DHHS listed him as an out-of-custody death. Assistant County Attorney Lonnie Albright reported that the death did not happen in the jail. The State Bureau of Investigation said it happened days later at a hospital.

Many sheriff’s offices file reports of out-of-custody deaths as a courtesy to DHHS, as Forsyth did in this case. But the report didn’t disclose when Neville was last seen appearing to be OK, when he went into distress or who the jailer was during those checks.

Neville’s charges were out of Guilford County. Guilford County Chief Assistant District Attorney Steve Cole said that Forsyth deputies requested a change to Neville’s bond terms so that they could release him to the hospital after a medical incident.

Cole said they were never told that Neville died. A judge issued warrants against Neville for failure to appear when he didn’t show up to court in January, after he died.

In June, The News & Observer learned of the SBI investigation into what happened to Neville and began asking more questions. Williams said SBI agents were asked to investigate an in-custody death in Forsyth County.

Williams said the SBI investigation concluded in April but he could say little else because both the bureau and O’Neill were waiting on an autopsy report.

What happened in the jail

A woman had accused Neville of pushing her off a front porch and punching her in the face and the back of the head, according to court records. She went before a magistrate and filed an assault charge. The woman has not responded to a Facebook message from the N&O seeking comment.

Police found Neville in Kernersville, a town that straddles the Guilford and Forsyth county lines, and took him to the Forsyth County jail.

Neville was booked into the jail at 3:05 a.m. on Dec. 1.

He wouldn’t be there long, though. At 3:54 a.m., Dec. 2, Neville had an unknown medical problem that caused him to fall out of the top bunk in the jail cell onto the concrete floor below. O’Neill said five deputies and the on-call nurse responded to Neville’s fall. When they came in, O’Neill said he was confused and disoriented.

“Mr. Neville was moved into an observation room to determine what was causing his distress,” O’Neill said. “Over the next 45 minutes Mr. Neville would sustain injuries that would cause him to lose his life.”

Prone restraint is a controversial technique still used by some law enforcement in which a person is handcuffed behind their back, placed on the floor and then has their ankles raised up to their wrists from behind.

The technique was used in the 2018 death of Marcus Smith in Greensboro. The N.C. Office of the Chief Medical Examiner labeled Smith’s death a homicide after he, too, suffocated while in the position.

Neville didn’t die at the jail. He was taken to Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center where he died two days later on Dec. 4.

“Good men and women made bad decisions that day and as a result a good man died and for that it was a tragic day and tragic situation,” said Sheriff Bobby Kimbrough, who did not take questions from the media.

The former officers charged

The News & Observer requested several weeks ago the public-record portions of all deputies’ employment files from the Forsyth County Human Resources Department but has not received them. O’Neill said that the deputies no longer work at the sheriff’s office but did not say whether they were fired or resigned.

O’Neill identified those charged as Detention Officers Sarah E. Poole, Antonio M. Woodley and Christopher Stamper, Corp. Edward J. Roussel and Sgt. Lavette M. Williams. The nurse is Michelle Heughins.

O’Neill said someone who is found guilty of involuntary manslaughter killed another human being by either a culpably negligent act or omission or failure to act. He said case law defines involuntary manslaughter as a killing without malice, premeditation and deliberation or an attempt to kill or inflict serious injury and that it is an unintentional killing.

The district attorney said criminal negligence in case law means a carelessness or recklessness that shows a thoughtless disregard of consequences or a heedless indifference to the safety and rights of others.

“We’re sorry the mistakes were made that day,” Kimbrough said. “I take responsibility for that as a sheriff. What I will tell you is that we’ll still give you the best of us. We will still serve the public and we’ll still stand up for what is right and what is true.”

Thanking protesters

Family members posted a notice of his funeral a month later on his personal Facebook page. People flooded Neville’s timeline with their love for the Greensboro man.

“This came all of a sudden and broke my heart,” one woman wrote. “Just know that he loved his family beyond measures and that’s why I love him.”

Neville’s estate is being represented by Grace, Tisdale and Clifton in Winston Salem. Neville’s children have directed all comments to the law firm. Grace took the podium Wednesday morning and spoke on behalf of the family.

Two of Neville’s children sat next to their attorneys but never spoke.

“I am happy we followed the DA’s advice and let it work itself out,” Grace said. “There could have been leaks in this thing and information given to the public and misinformation which would have been a disservice to the Neville family and to the process.

“I can tell you that the Neville family, though grieving, is satisfied by the process.”

Grace asked that the family be given time away from the public eye to continue to grieve.

Grace said he understands the cause of Neville’s death could lead to protests.

“We ask that no acts be committed in John Neville’s name that would not honor his life,” Grace said, with O’Neill adding that while he and the family support peaceful protests, violence will not be tolerated.

Grace went on to thank protesters who sat outside the governor’s mansion in Raleigh asking that he veto Senate Bill 168. The bill included an effort to limit what became public record in death investigations.

The provision, though requested by the state DHHS, had stalled last spring and wasn’t added into SB 168 until the middle of the night on the last scheduled day of the short session on June 26.

“His presence and his name was invoked last week in Raleigh in front of the governor’s mansion to urge the governor to consider vetoing a bill that would affect this case peripherally and his spirit and his name was heard by the governor,” Grace said. “It was a very peaceful protest by determined young people in Raleigh and the governor did veto that bill.”

Cooper vetoed Senate Bill 168, citing controversies surrounding the provision, only 48 hours before O’Neill issued charges against the deputies.

Everyone involved in the news conference said they would not answer questions to allow the deputies and nurse to have a fair trial.

Staff writer Dan Kane contributed to this report.