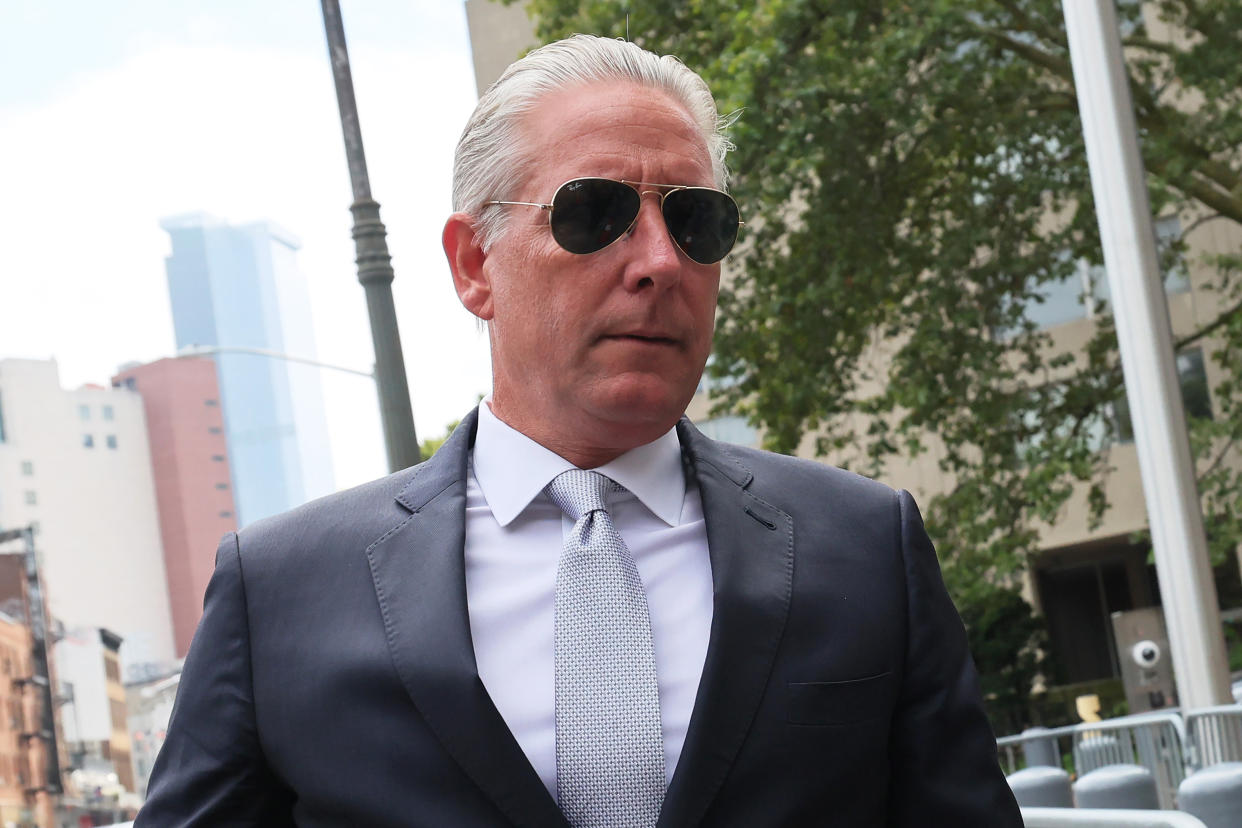

Former FBI spy chief Charles McGonigal gets 50 months in prison for helping sanctioned Russian oligarch find dirt on enemy

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

A former FBI spy chief was sentenced to just over four years in federal prison Thursday for abusing the skills and influence he gained in one of the most preeminent espionage jobs in the country to go to bat for a sanctioned oligarch with close ties to Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Charles McGonigal began working for the FBI in 1996 and headed the counterintelligence division at its New York field office from 2016 until he retired in 2018. After he left the bureau, he worked to help Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska target a rival businessman, leading McGonigal to plead guilty in August to conspiracy to launder money and violate U.S. sanctions.

The former FBI honcho sounded on the verge of tears as he pleaded for no prison time before learning his fate.

“Your honor, I am humbly asking for a second chance to prove to you and those that I’ve caused pain, suffering, and harm … that I will continue to be a law-abiding member of society,” said McGonigal, 55.

“I, more than anyone, know that I have committed a felony, and as a former FBI special agent, it causes me extreme mental, emotional and physical pain — not to mention the shame I feel in embarrassing myself and the FBI, the organization that I loved and respect.”

But Manhattan Federal Court Judge Jennifer Rearden said the veteran spy chief’s “extraordinarily serious” actions undermined the legitimacy of U.S. sanctions he once enforced, manipulated a regime imposed by three presidential administrations and greatly risked national security.

“If nations such as Russia can avoid or influence these sanctions through conduct like Mr. McGonigal’s, then the sanctions will be ineffective, increasing the risk of war,” the judge said.

Rearden said the gravity of McGonigal’s conduct was exacerbated by how he carried it out and his steps to conceal it.

In “one of the highest-ranking, most important intelligence positions in the country,” the judge said, “McGonigal began a concerted, years-long effort to exploit the information, his skills and the contacts he had cultivated for the purpose of developing relationships that could financially enrich him after he left the FBI.”

Manhattan Assistant U.S. Attorney Hagan Scotten said between the spring and fall of 2021, McGonigal worked to find ways to get Deripaska’s rival — fellow oligarch Vladimir Potanin — on the sanctions list and probe Potanin’s interest in a company McGonigal and Deripaska were vying to control.

He said McGonigal was keenly aware his research for Deripaska violated sanctions imposed three years before, having received classified information about the aluminum tycoon and his addition to a list of Russian oligarchs with close ties to the Kremlin U.S. authorities were seeking to exert financial pressure on them over Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea in Ukraine.

Deripaska was also a person of interest in Robert Mueller’s probe of Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election, though the oligarch was never charged with any crime in the investigation.

Scotten told the judge the funds McGonigal made from Deripaska represented a fraction of the “millions” he hoped to earn before he got caught, and that he also tried to get the billionaire off the sanctions list. The prosecutor said the the deep betrayal by “one of the people most entrusted with this country’s secrets” was born from greed as McGonigal sought “to turn his credentials into cash” — and that nobody knew better than McGonigal what Deripaska represented.

“Your honor, Deripaska is a notorious Russian oligarch — a man who is powerful not only because of his vast wealth, but because of his close connections to the Russian state and to Vladimir Putin personally,” Scotten said.

“A man who wields power not only because of his bank account, but because he’s willing and able to use murder, threats, espionage — all the resources he has — as one of Putin’s most trusted henchmen.”

The feds in September charged Deripaska, who founded the aluminum empire Rusal, with evading U.S. sanctions. They also charged a New Jersey woman who allegedly helped both the evasion and Deripaska’s arrangments for his partner to give birth to their baby on American soil. The News could not reach his lawyer for comment.

DuCharme said his client meant no harm and had never dealt with Deripaska directly in carrying out the research. He cited top-secret records under seal and asked the judge to recognize McGonigal’s professional contributions in a storied 22-year career.

“Simply put, judge, his work has got to count for something,” the attorney said.

Rearden also imposed a term of three years’ supervised release and ordered McGonigal to pay a $40,000 fine. In September, he pleaded guilty in a separate Washington case alleging he concealed a $225,000 payment from an Albanian intelligence officer. McGonigal is set to be sentenced in that case on Feb. 16, 10 days before he has to turn himself in to serve his New York sentence.

_____