Former Gators wrestling coach Keith Tennant should not be a forgotten man in UF sports history

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

One nice thing about sports is how the names change but legacies live on.

At Florida games, a Percy Harvin run might have reminded fans of Wes Chandler. Colin Castleton swatting away a shot might spark memories of Joakim Noah. A Trinity Thomas vault could conjure visions of Bridget Sloan.

The past lives on through the present. With one unfortunate exception.

Remember the Gator Grapplers?

That's what Florida’s wrestling team was often called in headlines. Yes, kids, back when Hulk Hogan was just a skinny bass player in a Tampa rock band, there was real wrestling in our state. And it even made headlines.

Toney's chance:Ex-Gator receiver Kadarius Toney needs to take advantage of his lifeline with Kansas City

Spurrier Way:Whitley's Believe It Or Not: Hey Tennessee fans, you can now drive all over Steve Spurrier

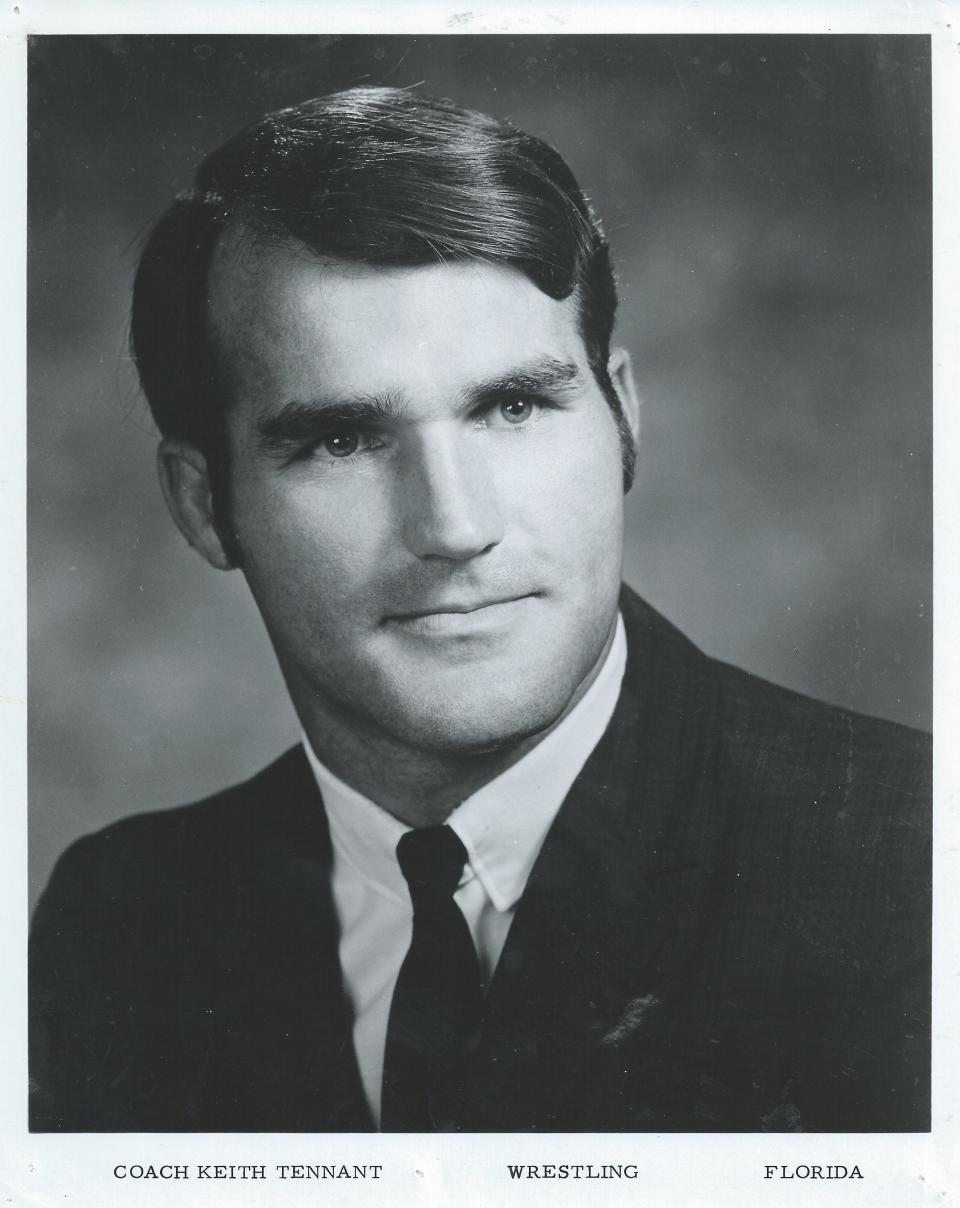

If you remember that, you might recall the name Keith Tennant. What you might not know is the architect of Florida’s wrestling program died a few weeks ago.

His legacy should not suffer the same fate.

Tenant started from nothing and built one of the SEC’s best programs, only to see it all shot down in a decision that still smells bad after half a century.

“It was only a 10-year period,” said Chet Sanders, one of Tennant’s wrestlers. “But it was golden to us.”

These days, UF teams seem to click off one or two NCAA championships a year. There wasn’t a lot of gold for Gator fans to cling to when Sanders and his buddies were on campus.

“At the time, Florida didn’t have a lot of SEC championship teams or individuals,” Ron Pinnell said. “It was swimming, track and golf.”

Then along came Tennant.

“He was the glue that put us all together,” Tim Granowitz said.

Wrestling not part of Southern culture

It wasn’t easy. When the SEC got into the wrestling business in the late 1960s, the sport wasn’t nearly as ingrained in Southern culture as it was (and still is) up North.

Tennant had wrestled on UF’s club team and become an instructor at the College of Physical Education, Health and Recreation. Athletic Director Ray Graves offered him the coaching job.

Tennant had to borrow equipment from the intramural department, but he at least looked the part of a big-time coach. He was built like a fire hydrant, with a chiseled matinee-idol face and blue eyes.

Tennant could have easily slipped into the era’s standard coaching role. Steely-eyed, butt-chewing, my-way-or-the-highway guys in polyester shorts dotted the land.

Tennant was patient, caring and charismatic. No one can recall him ever saying a negative word. Not even about Georgia.

“He made us feel like we were special,” Sanders said.

They needed the love. Wrestling might be the most physically demanding sport ever devised. The Gator Grapplers would run 3.2 miles a day and climb ropes before practice even began.

Their world revolved around “making weight” – stepping on a scale before a meet and being under the weight limit for their class.

Back then, the athletic department did not have a staff of nutritionists monitoring carbs, proteins and hydration levels. The wrestlers would nibble at meals, sip cups of hot tea and run, run, run to shed a final pound or two.

Since misery loves company, it was a great way to bond.

“It was like mutual self-torture,” Sanders said. “(Tennant) was dealing with a bunch of people who were really on edge. But he knew how to handle that. He had a good sense of humor all the time.”

It went both ways. Wrestling coaches teach by doing, and Tennant relished mixing it up with his students.

He’d dare them to sweep him off his legs. It was such an impossible task that his wrestlers nicknamed their coach “Squatlow.”

The chemistry paid off. Gator wrestlers outnumbered the fans at early meets at Alligator Alley, but crowds eventually grew into the thousands. UF started producing NCAA qualifiers and had a 57-13 record in dual matches under Tennant.

Then he walked away.

One of his star wrestlers, Gary Schneider, had become an assistant and looked like a coaching prodigy. Tennant wanted to pursue his academic career. He’d taken the program about as far as he could, and he wanted it to continue to grow.

That it did.

The Gators won the SEC title in 1975 and entrenched themselves as a conference heavyweight. Then everything suddenly went dark in 1979.

Was Title IX the reason or the football program?

Title IX kicked in, and UF said equalizing resources for women’s sports forced cuts to men’s sports. But the school also eliminated women’s volleyball.

That led to decades of suspicion that football was the real heavy. Charlie Pell was freshly hired and determined to upgrade facilities.

The wrestling area in Alligator Alley would make a fine football weight room, certain power brokers thought. And the little ol’ non-revenue sport was spending money that could be going to more important things, like tackling dummies and polyester coaching shorts.

“It was a real shock to me when they dropped the program,” Schneider said.

That’s one reason you might not recognize names like Granowitz or Bill Teutsch or Henry Jackson, who’s believed to be the first Black wrestler to win an SEC title.

There’s been nobody to carry on their legacies. The Gator Grapplers are now mostly 70-year-olds trying to keep memories alive.

Like how “Squatlow” would still sneak into their practices after he retired and pounce on unsuspecting wrestlers. How he mentored them and helped them get jobs.

Pinnell was moving back to campus to start post-graduate work, when his van broke down in the Ocala National Forest. He eventually got to a payphone (no cell phones in those days) and knew who to call.

“Coach was there within an hour,” Pinnell said.

Tennant probably never told a soul. He met his wife, Laurie, in 1986. Six years later, he told her he had to go to an engagement at UF.

“For what?” she asked.

Tennant was being inducted into the UF Athletic Hall of Fame. He’d never even told his wife he’d been the school’s wrestling coach.

“He wasn’t somebody who was high on himself,” she said. “He had great humility.”

Tennant eventually became head of the Department of Health, Sports and Exercise Science at Kansas. He retired to Vero Beach, and his health faded the past few years.

He got a letter last year from Jackson. Part of it read, “I want to thank you for keeping your word to me in all that you said and promised ... I now look back on those years and see how we made history together.”

It lasted only 10 years, but the Gator Grapplers deserve to be remembered a lot longer than that.

So does the glue that put them all together.

David Whitley is The Gainesville Sun's sports columnist. Contact him at dwhitley@gannett.com. Follow him on Twitter @DavidEWhitley

This article originally appeared on The Gainesville Sun: Keith Tennant, Florida Gator wrestlers are gone but legacy should live on