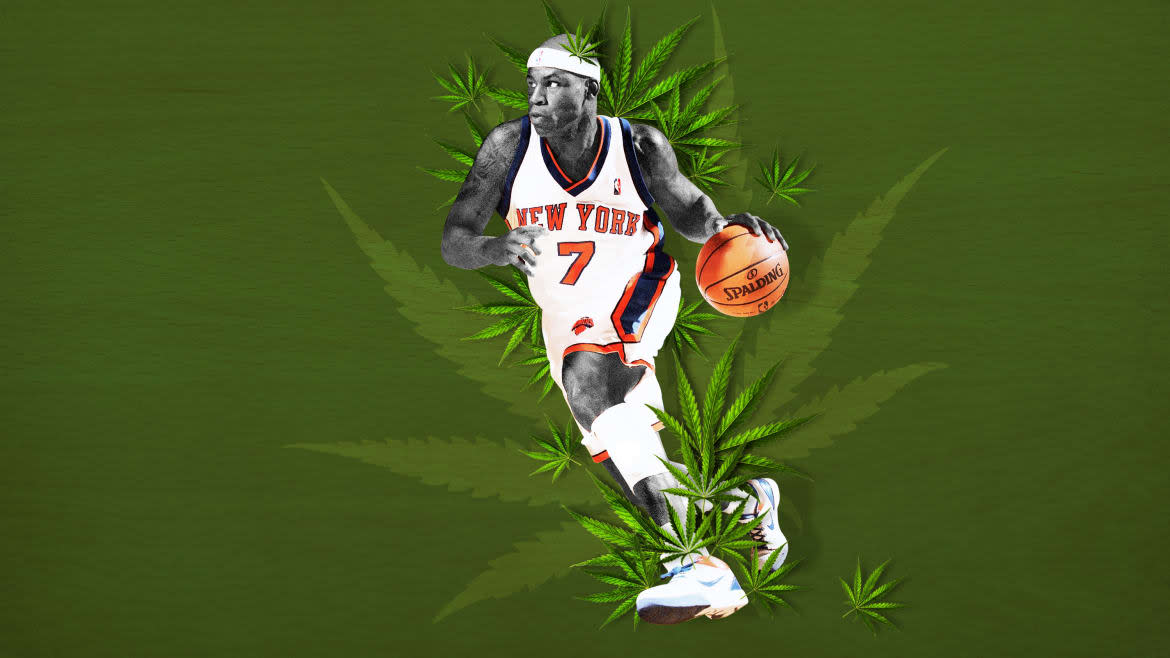

This Former NBA Star Wants You to Buy His Weed and End the War on Drugs

Al Harrington wanted to get busted for weed by the NBA. The 6-foot 9-inch forward was coming off surgery to repair a torn meniscus in his right knee in 2012. It was his 14th season in what would ultimately prove to be a 16-year career, but the recovery wasn’t going smoothly. He developed a staph infection and ongoing knee issues led to multiple invasive follow-up procedures.

Doctors prescribed Vicodin and then another painkiller, the name of which Harrington can’t recall. Despite adjusting the dosage and alternating the medications he ingested, it left him feeling perpetually drowsy and sluggish and the inflammation persisted. Thankfully, a friend visited him that summer in Colorado while he was rehabbing the swollen joint. Harrington found himself nodding off mid-conversation.

“Man, what is wrong with you?” Harrington said his friend asked. He rattled off the medications he was taking and the friend shot back: “Why don’t you stop taking that garbage.”

In lieu of synthetic opioids, his friend had come armed with a grab bag full of cannabis-based products, including “topicals, tinctures, capsules, and gummies,” Harrington said. It was a “godsend.”

The swelling in his knee subsided, and there were no harmful side effects. He continued to use cannabidiol (CBD) throughout the following season, even though he had been shipped from the Denver Nuggets to the Orlando Magic in August 2012. (Unlike Colorado, Florida has not legalized cannabis). Much to Harrington’s dismay, it didn’t register on an NBA-mandated drug test.

“I was hoping I tested dirty, so that I could tell the CBD story,” he said. Any fines, suspensions, or negative press would have been worth it, because the notoriety would have given him licence to publicly extol the benefits of cannabis. Since then, Harrington has devoted himself to doing just that. Beyond advocating for the medicinal use of cannabis by athletes, he’s fought to reduce sentencing for nonviolent, cannabis-based crimes, worked to increase participation for people of color in the multibillion-dollar cannabis industry, and created post-prison opportunities for those ensnared by the neverending war on drugs.

In 2014, Harrington co-founded Viola Extracts, a cannabis producer and wholesaler which boasts 100 employees and operates facilities in six states: Arizona, California, Colorado, Michigan, Nevada, and Oregon. Last year, Viola secured $16 million in a funding round.

The company takes its name from Harrington’s grandmother. In 2011, prior to Harrington’s own revelations about cannabis, he learned that Viola, age 79, was taking a bevy of medications to deal with her health issues, including glaucoma. Harrington had read an article outlining the possible benefits of cannabis, but initially, his grandmother was reluctant, to say the least. “Reefer?” she vehemently told her grandson. “No way I’m trying no reefer.”

The next morning, he visited Viola after practice and her pain had not diminished. “She said [her eyes] hurt so bad she could barely see,” Harrington recalled. Again, he gently prodded her. “You’re taking the medication; it’s not working,” he said. “Give it a chance."

Finally, Viola relented. The pain was so unbearable, his grandmother was ready to try anything. A friend of his had access to a dispensary, and recommended Vietnam Kush.

The cannabis was vaporized to allow Viola to ingest it, and Harrington saw her eyes get “glassy” he said. Laughing, Harrington told her: “Alright, grandma. That might be enough.” After a 90-minute nap, he checked to make sure she was OK. Not knowing what to expect, he found his Viola in her room, weeping. “I’m healed,” said Viola. For the first time in three years, she could read the words printed in her Bible.

Harrington started crying, too. “I can’t believe I got my eyes and my eyesight back,” he recalled her saying. “God gave me my sight back.”

In that moment, his entire outlook on drug prohibition swung 180 degrees.

Growing up in Orange, New Jersey, Harrington had seen the impact of the war on drugs first-hand. When he was in the eighth grade, classmates of his were pulled out of homeroom for a drug-related offense, he said. The idea that people in his community who had become addicted to crack cocaine were led to ruin first by smoking marijuana—the ancient, debunked “gateway drug” trope—had been hammered home. And Harrington took it as the gospel truth.

But his experiences opened up a whole new world. He began to self-educate. Initially a “strain nerd,” as Harrington called himself, over time he expanded his knowledge of cannabis’ medicinal purposes. Now, he sees his mission as “changing the narrative as a whole,” and informing the public of how “dynamic” cannabis and CBD can be, particularly for children suffering from epileptic seizures, and for HIV and cancer patients.

Harrington has gone under the knife four times since his NBA career ended, and his recovery regimen has remained the same. “Once the IV is out of my arm, that’s the last time I’ll use any pharmaceuticals,” he said. Though he’s 20 pounds over his playing weight, he boxes and goes snowboarding regularly. Were he able to treat his inflamed knee with cannabis while in the NBA, Harrington is sure he could have lasted another two years. Should the NBA reverse course, the current generation of athletes will reap the benefits he was denied. “CBDs could be that important to the league,” said Harrington.

A slew of NBA players past and present wholeheartedly agree with Harrington.

Brooklyn Nets star Kevin Durant wondered why cannabis remains banned by the NBA, as has Andre Iguodala; Golden State Warriors head coach Steve Kerr used cannabis to deal with the lingering pain from back surgery and said the NBA should afford athletes the same privilege; Charles Barkley, while making it clear he personally wasn’t in favor of recreational use, said cannabis had “really helped some football friends” of his; Hall of Famer Oscar Robertson backed pro-legalization efforts in Ohio; Cuttino Mobley and Clifford Robinson have also become cannabis entrepreneurs; and Stephen Jackson and Matt Barnes have long been staunch pro-cannabis advocates. But the movement got a massive boost in 2017 when Harrington sat down to interview former NBA Commissioner David Stern.

When asked about Stern, who passed away in January, Harrington grew quiet. “God bless,” he said, his head bowed. “God bless, Dave.” Prior to their conversation, he was “hella nervous,” unsure if he could get Stern—a skilled, brilliant attorney—to go where Harrington wanted him to go. He had carefully prepared a list of questions written on cue cards, but Stern beat him to the punch. After Harrington’s third question, Stern said: “I’m now at the point where, personally, I think [marijuana] probably should be removed from the ban list.”

He continued: “I think there is universal agreement that marijuana for medical purposes should be completely legal.”

For years, NFL players have similarly lobbied for changes to the league’s cannabis ban. A sport predicated on constant violent collisions certainly would benefit from a non-addictive form of pain medication. Especially since the overuse of team-prescribed opioids has led to numerous deleterious impacts. (One class-action lawsuit filed by ex-players was dismissed in 2019. A second case is ongoing.)

In March, those self-same activists finally scored a hard-fought victory. The new collective bargaining agreement between the NFL and NFLPA eliminated suspensions for testing positive, reduced the amount of testing that the league conducts, and increased the allowable amount of THC in a player’s blood. Fines will still be levied, though, and should a player decide not to enter the league’s treatment program and still test dirty four times, suspensions come back into play.

For Harrington, the policy changes represented a positive step, but he’s not entirely satisfied. “You’re also not testing players for alcohol,” he said via email. “Why even test players? That’s my question to them. If you’re going to take cannabis off the ban list, take it off the list.”

Other professional leagues, though, have chosen a different path. Major League Baseball no longer prohibits cannabis, and the National Hockey League stopped levying suspensions and fines should a player test positive.

As to why NFL took so long to relent and the NBA still won’t budge, Harrington has an answer: The use of marijuana by people of color has been demonized going back to the 1930s, and the NFL and NBA are both majority-black, unlike baseball and hockey.

“The two sports that are dominated by the black athlete, you guys are fucking policing cannabis like it’s crack cocaine,” he said.“That's bullshit.”

This, despite the fact that NBPA Executive Director Michele Roberts has made it clear she wants to see changes to the current collective bargaining agreement. While permitting recreational use might prove a bridge too far, if Roberts had her druthers, the league and the NBPA could at least agree to let their employees use CBD. But for now, the potential for running afoul of law enforcement has stymied her efforts. “If the feds tomorrow announce we’re no longer in the marijuana prosecution business then I’d think we’d have a deal by tomorrow night,” she told The Washington Post in December.

“We were hoping that there’d be some progress, but once Trump was elected and Jeff Sessions was appointed attorney general, the landscape changed,” she continued. “[I]t’s a source of frustration for me because it’s ridiculous. It’s just ridiculous.” (A spokesperson for the NBPA said Roberts would not be available for comment prior to publication, and sent a link to the December story in the Post. Earlier this month, the NBPA announced that Roberts would be stepping down at the conclusion of her second term as executive director.)

In an emailed statement, NBA spokesman Mike Bass told The Daily Beast: “We have regular discussions with the Players Association about a variety of matters, including marijuana and CBD. Those conversations are ongoing.”

Eventually, the NBA will see the light, Harrington believes. “They have to,” he said. The stigmas surrounding cannabis make it difficult, despite the number of athletes who’ve made it clear they responsibly partake in recreational use. (Six current NBA players told NBC that the total is somewhere between 50 to 85 percent of the league. Then again, they did so anonymously.)

Harrington, though, wants to know what’s stopping the NBA from permitting at a minimum medicinal use: “Why are you fighting it? What information do you have that they’re not privy to that you’re holding back. Prove it. Show it.”

Despite the abundant profits, the cannabis industry is not without potential pitfalls, as Harrington found out. In 2018, a Viola growing operation in Detroit was raided. While Harrington was confident that he and his staff had checked all the proper boxes and complied with all the necessary state and local regulations, perhaps he’d erred, somehow. Maybe some tiny mistake had led to the property being seized, and guns drawn on his aunt, who manages the facility. Despite trying to show the authorities that all their paperwork was in order, both his aunt and lawyer were dragged out of the facility by the police in handcuffs.

It was a teachable moment. Were he not a well-known athlete whose finances allowed him to remain solvent throughout the course of the legal process, “we would have been guilty, just because we couldn’t fight it,” he said.

Getting started in the industry is an expensive proposition. It took Harrington two years to raise $8.5 million dollars from friends and family members. For those not as fortunate, “they get raided, take everything... now you just ruined someone’s life again—this one opportunity they had to create generational wealth.”

The charges were ultimately dismissed, but the raid cost his company over $20 million, by Harrington’s estimation.

The ongoing pandemic hasn’t harmed his cannabis venture. Far from it. “Sales have doubled with the sudden rush of people staying at home,” he claimed via email, as his customers have made sure their cupboards don’t run bare. “The challenge is going to be making sure that we can keep up with the demand at this point.”

But Viola isn’t just a for-profit venture. Harrington remains devoted to helping the untold number of people who had their lives upended by the war on drugs. Right now, anyone with a prior criminal record won’t be granted the necessary licensing. Harrington was in Albany on March 2, just before the coronavirus pandemic hit, to meet with Gov. Andrew Cuomo and discuss cannabis. But Cuomo’s need to quickly introduce legislation expanding his authority to address COVID-19 scuttled their scheduled conversation.

Recently, Viola launched Root and Rebound, a nonprofit which provides the recently released toolkits for re-entry into society, including job placement, housing assistance, educational efforts, and policy advocacy. Long-term, he hopes Viola will employ many more non-violent offenders. Scrubbing a drug charge from someone’s record after they’ve done their time would have a huge impact on those trying to get a minimum-wage job in, say, the service industry, he explained. The irony is galling. Spend years in prison for selling a small amount of cannabis on the street, get released and see largely white entrepreneurs doing the exact same thing but at a massive scale, he said.

“You go to jail, do your time, and you come back home and you’re still in jail.”

Got a tip? Send it to The Daily Beast here

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.