Former Sacramento teacher is a distant descendant of one of the richest people in history

Rachel Edelson, a longtime Sacramento-area teacher, has aristocrats and celebrities in her family tree, but her maternal pedigree translated mostly to stories of bygone wealth.

Edelson, who now lives in Berkeley, is the daughter of jazz legend Benny Goodman. Edelson’s mother, the former Alice Hammond was the great-great-granddaughter of 19th century rail and shipping tycoon Cornelius Vanderbilt, among the richest Americans in history when adjusting for inflation.

By the time Edelson was born in 1943, Vanderbilt’s heirs had almost completely squandered his fortune through failing to adequately diversify the family’s financial interests and spending extravagantly.

“My mother remembered not only traveling in their own car on the railroad as Vanderbilts,” Edelson said. “She remembered dinner parties of let’s say 20 people with a footman at each place and not silverware, goldware.”

For people like Edelson, having a historically-important ancestor is part of who they are, can be an instant conversation starter and is getting easier to determine with the internet. But these connections don’t always mean a lot in tangible terms, including when Edelson was young.

“It meant zero,” Edelson said.

‘A part genetically’

Edelson isn’t the only descendant of Cornelius Vanderbilt to not get much from the association. Her third cousin is news anchor Anderson Cooper through their great-great-grandfather William Henry Vanderbilt.

William Henry Vanderbilt, Cornelius’s son and primary heir upon his death in 1877, doubled his father’s estate before dying in 1885. The following generations were a different story, people like Cooper’s maternal grandfather Reginald Claypoole Vanderbilt who gambled away much of his inheritance. Other Vanderbilts built opulent mansions that no longer stand on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan.

In 2021, Cooper wrote a No. 1 New York Times bestseller with Katherine Howe, “Vanderbilt: The Rise and Fall of an American Dynasty.” In the book’s introduction, Cooper noted how the Vanderbilt name had little bearing on his life or meaning for him prior to the birth of his son in 2020.

“I’ve always gone out of my way to avoid mentioning my relation to the Vanderbilts,” wrote Cooper, who didn’t respond to an interview request. “When someone would find out and ask me, ‘What was it like to grow up a Vanderbilt?’ my response was always the same. ‘I don’t know,’ I’d say. ‘I’m a Cooper.’”

Another prominent descendant of the Vanderbilt family is Edelson’s first cousin once removed, actor Timothy Olyphant, who didn’t respond to an interview request. Edelson’s never met Cooper, though she admires his work. She formerly knew Olyphant’s father John Vernon Bevan Olyphant fairly well, though she’s been out of touch, she added.

Edelson grew up playing piano and eventually performed with her father at Carnegie Hall. As for the Vanderbilt ties, they’ve never been of much interest to Edelson, though when her daughter was 12 or 13, they attended a Vanderbilt reunion and toured one of the family’s remaining mansions in Newport, Rhode Island.

Asked if her Vanderbilt connection helped make her who she was, Edelson replied, “I would say it played a part genetically.”

Sometimes, a reunion at a distant mansion with strangers is the best a person might be able to hope for should they unearth a link to a famous ancestor.

Thomas Best, a 79-year-old California State University, Sacramento professor emeritus who lives in Granite Bay, spent years researching a bit of family lore that he might have been related to former U.S. President Thomas Jefferson and his slave Sally Hemings.

Best and his wife attended a Hemings family reunion in the 2000s at Jefferson’s Monticello estate and plantation in Virginia, getting to see some rooms the general public wasn’t allowed in. But Jefferson and Hemings don’t have a major impact today on Best’s life.

“I really don’t talk about it,” Best said. ‘I don’t spend a lot of time with friends or anything talking about the Jeffersons.”

How connections to famous ancestors are made

Some people like Edelson or Cooper were more or less born knowing their ties to a famous person from history. Others like Best sussed it out by making in-person research trips long before websites like Ancestry.com began allowing people to scour the U.S. Census data and other records from home.

There are those skeptical that ancestral research can lead to any famous connections, including University of California, Davis history professor Ari Kelman. “My guess is that the overwhelming majority – the massive majority of people in the United States would not be tracing their lineage back to anyone famous or infamous,” Kelman said.

Still, it’s getting easier to learn about famous potential ancestors with genetic tests through websites like 23andMe. While there are privacy concerns around these tests, they can yield interesting results.

James Scott, an archival services specialist at the Sacramento Public Library discovered through a genetic test that he’s in French King Louis XVI’s haplogroup. This means they may or may not be a direct relation but they at least share a common ancestor through Scott’s paternal line “which is still cool,” he noted in an email.

Sam Ancona Esselmann, a senior product scientist for 23andMe said that paternal haplogroups can trace Y chromosome or mitochondrial DNA through generations. She noted that mitochondrial DNA “is inherited in a similar way to the Y chromosome in the sense that it doesn’t get shuffled in every generation. So it’s, you can trace it really far back in time in theory.”

Scott’s not the only person to learn of a noteworthy potential relation through a genetic test.

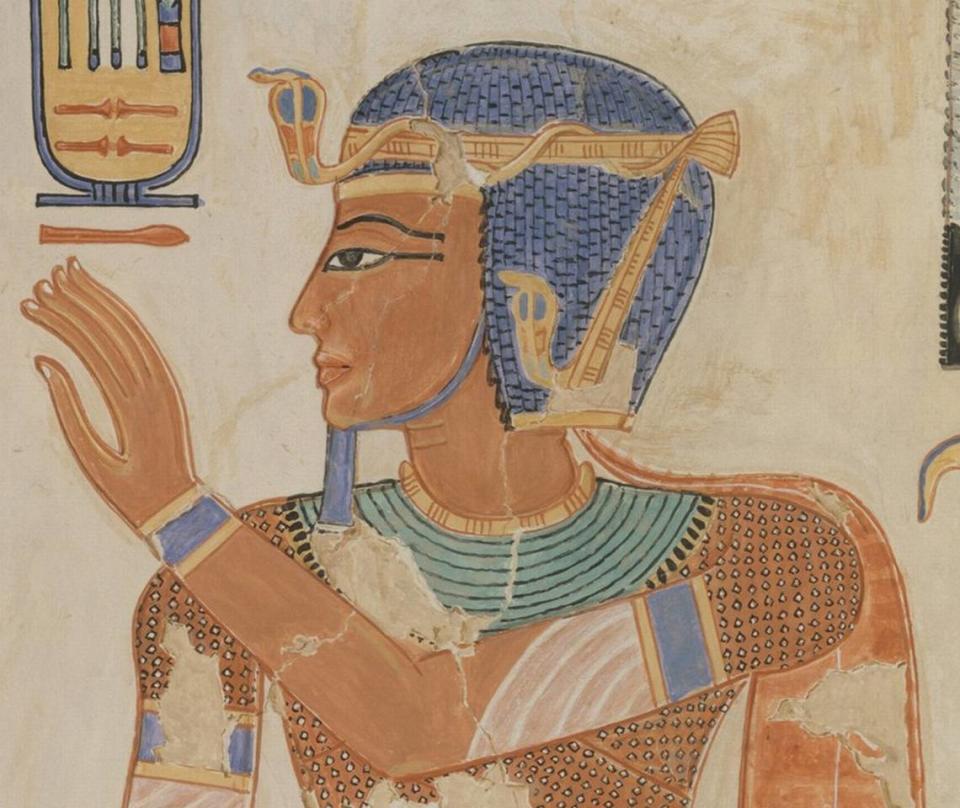

Dexter Caffey, a 50-year-old technology business owner who lives in the Atlanta area, spit into a tube to take a 23andMe DNA test in November 2021. When he got the results back on Christmas Day that year, he learned that he was among 1,700 23andMe customers who shared a haplogroup with Egyptian Pharoah Ramesses III.

Caffey did some research to learn more about Ramessess III. When he saw a picture of a sculpture, he screamed at his resemblance to it, startling his wife. “When I saw the sculpture, that was my reality,” Caffey said. “Nobody can look identical to a 4,000-year-old sculpture like that.”

Caffey’s been reading books on Ramesses III, noting the ways the two are similar and contemplating a trip to Egypt. Since he shared the results of his 23andMe test on social media, friends and family have been motivated to get tests, too.

“I think about that sculpture every single day and I just shake my head, wondering how in the world is this even possible to look so similar to something like this?” Caffey said.

Forging their own path

Cooper’s parents made clear to him, he wrote in his 2021 book on the Vanderbilts, that there wasn’t any Vanderbilt money left and that no trust fund awaited him.

“They wanted me to be my own person, and I am grateful to them for that,” Cooper wrote. “I don’t think I would have been as driven as I have been if I had grown up believing there was a pot of gold somewhere waiting for me.”

Edelson didn’t grow up with Vanderbilt money either. Her father was already a famous musician and able to support a family by the time he married her mother in 1942.

Her parents met because Alice’s brother John Hammond worked with Benny in the music industry. Goodman’s family didn’t approve of the marriage because Alice was not Jewish. She’d been married before, too, having had three children with an English Parliament member Arthur Duckworth.

“‘Atonement’ is set in a house like the one that my mother lived in (with Duckworth in England),” Edelson said. “Endless rooms and maids’ quarters.”

Alice Goodman never provided the funds for the Goodman family to live on, not that this would have been possible. When Edelson was young, her grandmother Emily Vanderbilt Sloane Hammond donated her 277-acre Dellwood estate in Mount Kisco, New York to the Moral Re-Armament movement, something that Edelson’s mother and mother’s siblings resented.

Edelson only got glimpses of her mother’s past life, such as hearing that her grandmother did her hair herself for the first time at age 70 or that her mom couldn’t cook anything beyond Caesar salad or onion rings, having to use every pot in the kitchen to make the latter.

Still, while Alice Goodman had an aristocratic vibe, she was anything but snobby.

“My friends adored her,” Edelson said. “They often found her the one adult who listened to them the best.”

Edelson’s parents have each long since died. Five years ago, she divorced her third husband and prepared to move from Curtis Park to Berkeley, finally selling the piano she’d stopped playing years before, after concluding that her father never would have played with her were she not his daughter.

Instead, Edelson forged her own path professionally, moving to the Sacramento area in the 1970s and teaching English composition through Sacramento City College and UC Davis. “What I became more and more interested in was teaching my students never what to think but how to think,” Edelson said. “Because that’s more and more missing from education.”

Edelson’s given occasional interviews about her father over the years and at 80, is working on a book about their relationship that has a potential title of “Dreamswing.”

She noted the diametric difference between the privilege of her mother’s early life and the childhood circumstances of her father, who grew up one of 12 children to Russian Jewish immigrants in Chicago and remembered days with no food in his house.

“My ancestors represent the two most opposite dimensions of America, impoverished Jewish family having fled Russia from the pogroms and Vanderbilts,” Edelson said. “I like very much having those two bloodlines in me. I think it’s very interesting. I think it’s an honor.”