Fort Lauderdale floods highlight climate risks to South Florida’s airports, seaports

Seaports and airports are the lifeblood of South Florida’s tourism-based economy. But as the relentless rains that swamped Fort Lauderdale last week illustrated, those critical transit and supply chain hubs are vulnerable to debilitating flooding.

Local authorities, state legislators, airlines and seaport managers have understood the risks for years — and they’ve already committed to spend millions of dollars to protect against storm surge, king tides and downpours.

But the Fort Lauderdale deluge also underlines that upgrades can’t come quickly enough. Scientists warn that as climate change causes sea levels to rise and rainfall to intensify, it raises the chances of events like last week’s. Meteorologists classified the rain as a 1,000-year event — up to 26 inches in just a day — but epic rains have occurred more frequently in the last few decades.

And the disruption and damage didn’t come from a tropical cyclone or hurricane but a low pressure system far off in the Gulf of Mexico, its tail training thunderstorm after thunderstorm over the city. The downpours turned Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood International Airport into a lake, grounding flights for two days. Flooding also temporarily stopped tanker trucks from loading fuel at Port Everglades, leading to gas shortages that are still reverberating throughout South Florida a week later.

“The ports and airports of both Miami-Dade and Broward County are tremendous economic engines that generate tens of billions of dollars,” said Jennifer Jurado, chief resilience officer for Broward County. “There are close connections between their operations, so a disruption at any one of them can have significant economic implications.”

And that’s not to mention the 1,000-plus and counting homes damaged and the deep water that filled City Hall.

Fort Lauderdale airport at high risk

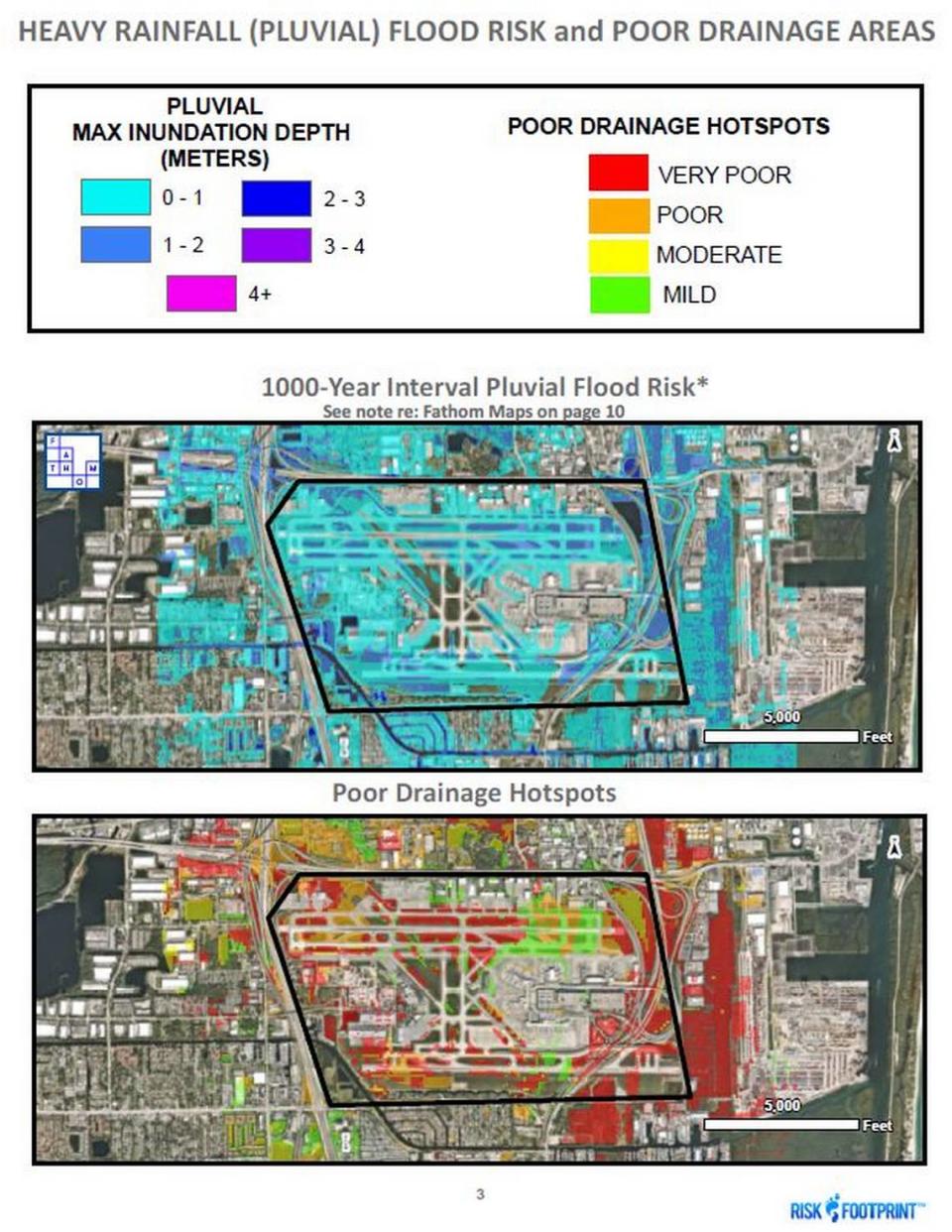

The Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood International Airport is particularly vulnerable to flooding, given its low elevation, poorly draining soil and its proximity to the coast, according to a report from Coastal Risk Consulting, a private company that explains a specific property’s risk of flooding and other natural hazards.

Besides rain, the Fort Lauderdale airport is also at risk of tidal flooding from sea level rise. A March report from the Brookings Institute, titled “America’s airports aren’t ready for climate change” mentions Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood International Airport by name.

“There are a lot of areas on the property and around the property that are so low and marshy that they’re actually having tidal flooding now,” said Albert Slapp, who heads Coastal Risk Consulting. The firm’s report, which relies on FEMA flood models, shows the problem getting worse over the next four decades.

“Does this mean that it’s inevitable? No,” said Slapp. “They can raise it up or put pumps in or use other controls. They’ll have to.”

In fact, Florida’s Department of Environmental Protection regularly includes the airport in resilience grants designed to do just that. The latest round of state “Flooding and Sea Level Rise Resilience” grants includes $1.6 million for a new pump station at the Fort Lauderdale airport and $3 million for a new stormwater system.

The new pump and stormwater system weren’t build in time to deal with the April 12 rainfall that flooded the property. But even if they were, those systems aren’t designed to handle anywhere near 26 inches of rain in a single day. Most drainage systems in Florida are designed to handle from three to six inches of rain over that period.

Raising Port Everglades

It’s not just air travel that was disrupted. So were daily commutes across South Florida because of gas shortages that lingered more than a week after the storms moved out.

Port Everglades supplies 40% of the gasoline that enters Florida — but tanker trucks stopped picking up fuel on April 12 after the port became too flooded to operate. Although the water drained and the majority of operations were back to normal by April 18, fuel shortages continue as gas stations struggle to catch up to demand from panic-buying drivers.

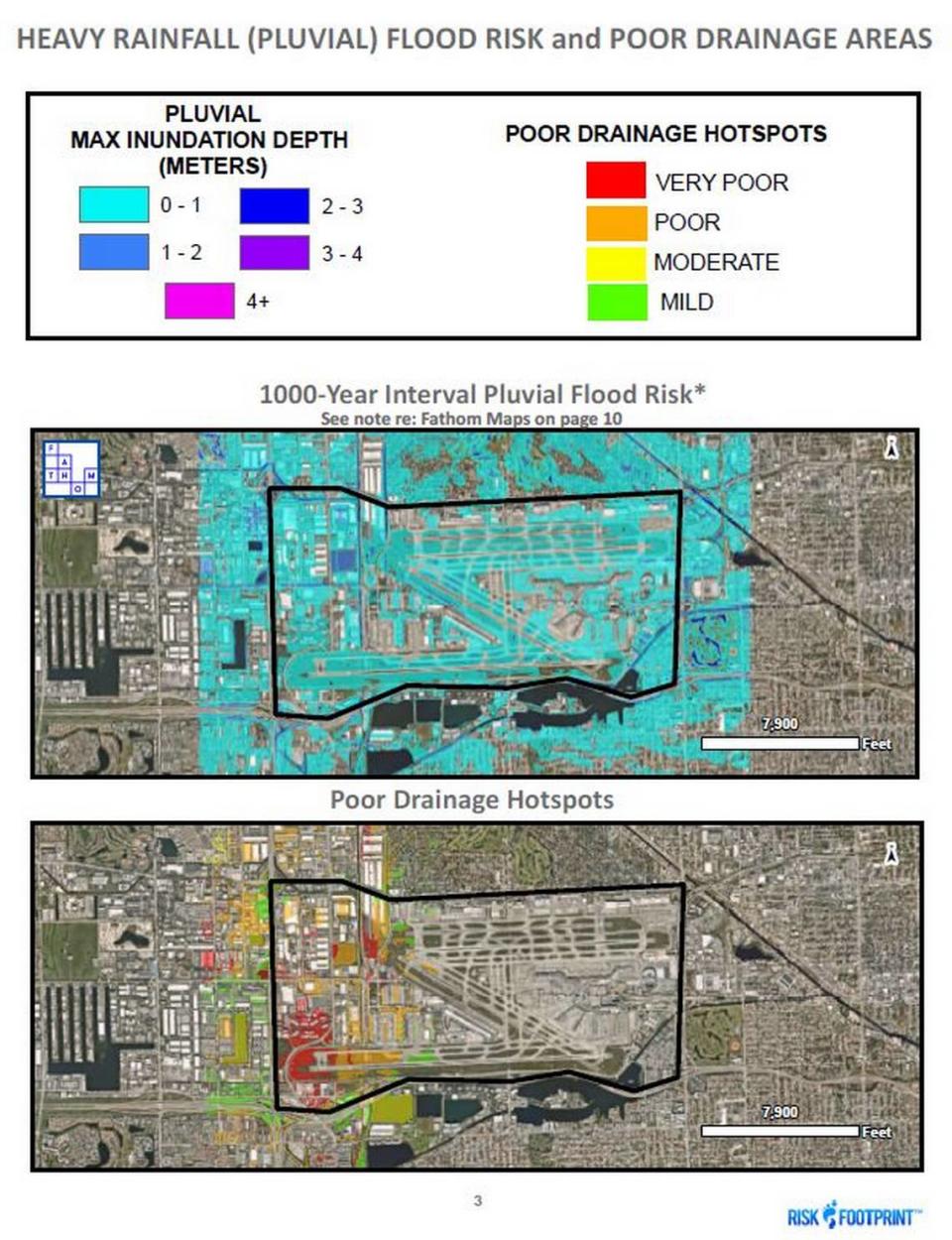

A risk report from Coastal Risk Consulting shows that Port Everglades has some drainage issues, but its main challenge will be sea level rise and tidal flooding. Small areas of the port are already at risk for eight days of tidal flooding a year, according to modeling from NOAA and NASA shown in the report.

But by 2040, the south end of the port will be vulnerable to 85 days of tidal flooding a year, if authorities do nothing to adapt. By 2060, the port is projected to see 360 days of flooding a year, unless it adapts to sea level rise, according to the report.

Authorities are already planning to raise the port in the future, although that work hasn’t started yet. This year, Port Everglades won a $32 million Resilient Florida Infrastructure Grant from the state which will fund a project to replace the aging bulkheads on the north end of the port. The new bulkheads are designed to withstand 4.36 feet of sea level rise by 2095.

Questions MIA’s future

American Airlines raised questions about the future of Miami International Airport in its 2021 Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) report. Citing the airport’s vulnerability to sea level rise flooding, American wrote that it was looking into ways to shore up its flood defenses “and, as a last resort, considering options for relocation to areas further inland.”

Miami International Airport faces less flood risk than Fort Lauderdale’s airport and Port Everglades, according to a risk report from Coastal Risk Consulting. But in a 1,000-year storm, it would still see about three feet of flooding, according to FEMA models shown in the report.

“The Fort Lauderdale airport looks worse to me than Miami, but they both get a lot of water above the ground surface with this type of rainfall that just keeps coming,” said Slapp.

Although 1,000-year rainfall events are rare — by definition, they have a 0.1% chance of happening in a given year — Slapp said people shouldn’t get complacent.

“We use the phrase 1,000-year storm to indicate that this level of flooding isn’t as frequent as a 10-year storm or a 100-year storm,” he said. “But things are changing with climate change and Mother Nature is throwing more and more stuff at us.”

As the planet gets warmer, the atmosphere is able to hold more moisture, and scientists expect rainfall events like the Fort Lauderdale storm to become more common. “The literature is very clear that those are increasing in intensity, frequency and sometimes also duration,” Andreas Prein, a project scientist at the National Center For Atmospheric Research, told the Herald on April 16.

This climate report is funded by Florida International University, the Knight Foundation and the David and Christina Martin Family Foundation in partnership with Journalism Funding Partners. The Miami Herald retains editorial control of all content.