Fort Worth’s 1936 Frontier Centennial ignored Black history. This event filled the void

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Fort Worth’s Frontier Centennial in 1936 has been well documented by the late Mike Nichols and by Richard Gonzales, history columnists for the Star-Telegram, and in Jan Jones’ book, “Billy Rose Presents Casa Mañana.”

It’s one of the proudest moments in the city’s history, when Fort Worth stuck it to Dallas, which had been tapped by the legislature to be the official site of the Texas Centennial Exposition.

While public attention was focused on the Frontier Centennial, another more modest celebration was going on a few miles away dubbed “A Century of Negro Progress.” It is not better known today because Billy Rose’s spectacle got all the spotlight.

The Frontier Centennial exposition celebrated Texas history with an emphasis on fun over education. The original idea was to honor all of the state’s history with a kind of “Six Flags Over Texas” theme. But as plans advanced, only certain groups were recognized — specifically, those that fit into Billy Rose’s “Wild West” theme.

That was why the city’s Black leaders decided to hold their own celebration, coinciding with the annual Juneteenth celebration. The name of the celebration — focusing on progress — was a reminder that African Americans also had a lot to be proud of.

It was set up in Como Park, part of the west side Black neighborhood. Lake Como had begun as a “trolley park” at the end of the Arlington Heights streetcar line years before.

The Lake Como event was led by T.S. Boone, pastor of Mount Gilead Baptist Church, the biggest African-American congregation in Fort Worth. He had the title of general director, and Allen R. Griggs of Dallas was producer. Edward H. Boatner of Wiley College in Marshall, Texas, was in charge of the music and assembled a large chorus.

Preparations got underway in the middle of May to transform a 10-acre site into exposition grounds. Construction included an exhibit hall, sports arena and amphitheater. In addition, the old Lake Como dance pavilion was rebuilt. Construction costs were capped at $6,000, raised through private subscriptions, mainly from Black middle-class people, very different from the Frontier Centennial, which cost $5 million (including $1,000 a day just for Billy Rose’s salary) and was funded by deep-pocketed businessmen like Star-Telegram publisher Amon Carter and William Monnig.

The Frontier Centennial had fan dancer Sally Rand, Paul Whiteman’s orchestra, and a performing elephant, “Jumbo”. The celebration of African-American accomplishments hoped to bring in heavyweight boxer Joe Louis, film comedian Stepin Fetchit and “several big-name” bands. They also hoped to get Ohio State track star Jesse Owens, who was going to the Berlin Olympics in August.

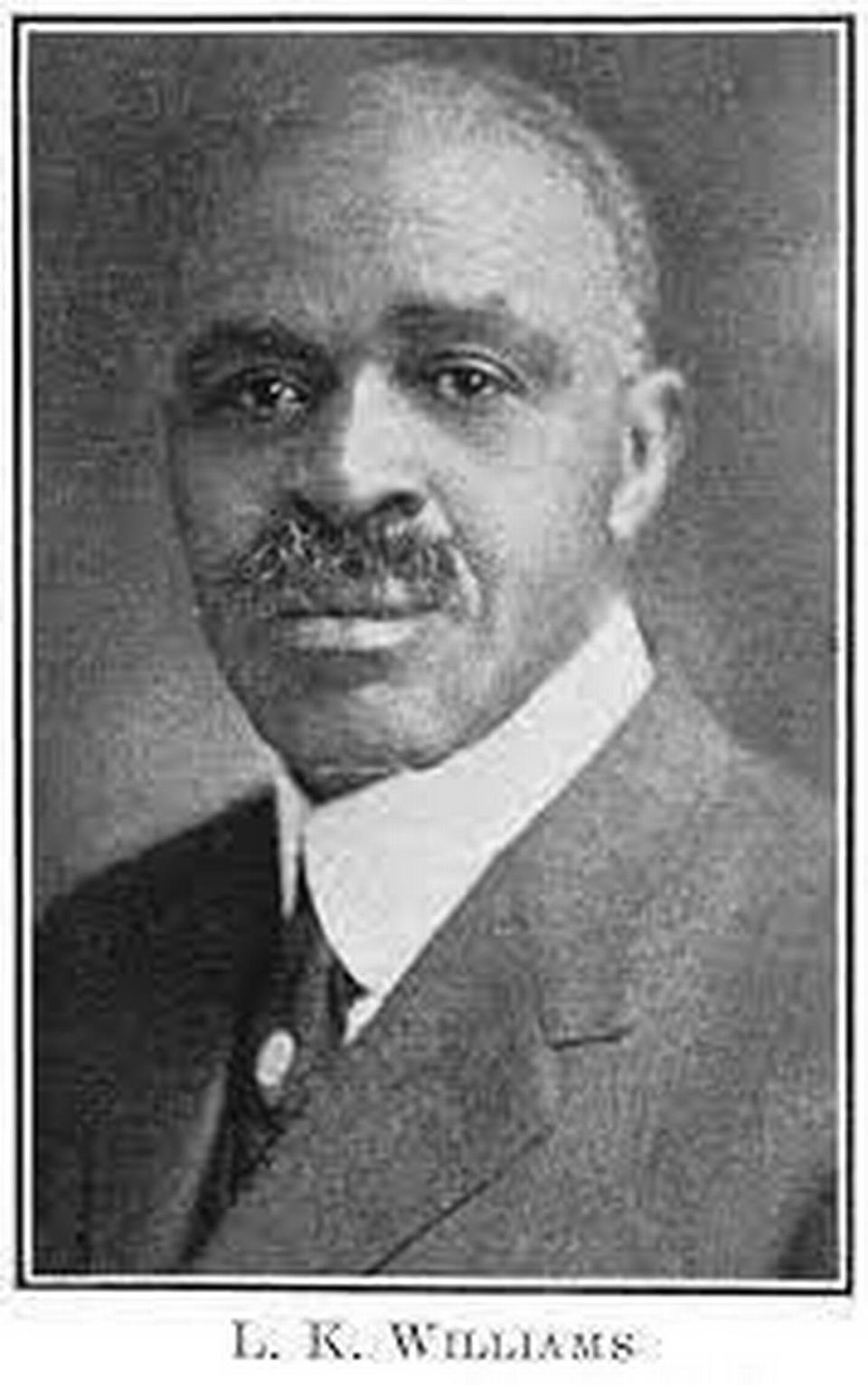

The exposition highlighting African-American progress highlighted a homegrown success story, the Rev. L.K. Williams, former pastor of Mount Gilead who was at the time pastor of Olivet Baptist Church in Chicago, considered the largest Black church in the world, with 15,000 members.

The event did not have a season-long run like the Frontier Centennial; it was really a riposte, not a competing celebration. The Frontier Centennial ran from July 18 to Nov. 28. The event celebrating African-American progress opened June 15 and wrapped up four days later, on June 19, which was definitely a statement.

The list of celebrity acts was rather thin due to the short planning time and relatively small budget. Early hope of putting on a production of “Porgy and Bess” was unrealized, and neither Joe Louis nor Jesse Owens accepted their invitations. Owens was training for the Olympics, and Louis was scheduled to fight Max Schmeling for the heavyweight boxing title on June 19. Stepin Fetchit was also a no-show for reasons unstated.

Headliners, instead, were “Gutwer, the Human Pin Cushion” and “Yerger the Hindu Magician.” The high point of Yerger’s act was “resurrecting” his assistant who had been “buried alive” in advance.

Other attractions included an educational exhibit, a historical pageant and a 22-mile footrace. The bigger-name bands scheduled to perform were “Boots and His Buddies” and Don Albert. Boone also promised that the famous Cab Calloway and his band would come to Fort Worth to play in what was promised as an extended exposition to run through October, but that didn’t materialize.

Boone predicted attendance of 500,000 spread across “five months” (June-October), still hoping for an extended exposition. The prediction of half a million visitors was based on Boone’s calculation that 5 million Black people lived within a 200-mile radius of Fort Worth. He explained to a Star-Telegram reporter that it was reasonable to expect “a tenth of them will visit the show.”

The Frontier Centennial, which opened July 18, did not just ignore Black history, it initially excluded Black people from the grounds, other than bus boys and servers working at Casa Mañana. One of those busboys was I.M. Terrell high-school student Marion Brooks, the future Dr. Marion Brooks who went on to spearhead the civil rights movement in Fort Worth. Brooks would later recall his job was the only way he could have seen the Casa show.

The segregated admission policy changed only after the “Jumbo” production failed to draw the expected crowds because the building was stifling hot. In desperation, Frontier Centennial management threw open the doors to Black customers.

The big day for the event celebrating African-American progress was a Friday, Juneteenth, starting at 6 a.m. with a “sunrise breakfast (and) dance.” People who attended that could go home and rest before the rest of the day’s activities that afternoon, which included the appearance of McGruder, “the Human Pin Cushion” and the footrace, which started at Arlington Downs racetrack.

William “Gooseneck Bill” McDonald, who was Texas’, if not the nation’s, most famous Black person, was the guest of honor, delivering one of his captivating addresses. He had to compete with “rodeo” events, a pantomime show, plus assorted “bathing beauties, pageantry and magic.” The biggest draw of the day may have been an historical pageant of African-American history that was an impressive combination of dramatic reenactment, colorful costumes and gospel singing.

With that, the celebration concluded, and, unlike the Frontier Festival, it never saw a second year.

Author-historian Richard Selcer is a Fort Worth native and proud graduate of Paschal High and TCU.