This Fort Worth lawyer blazed Texas legal trails. Now a children’s book shares his legacy

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

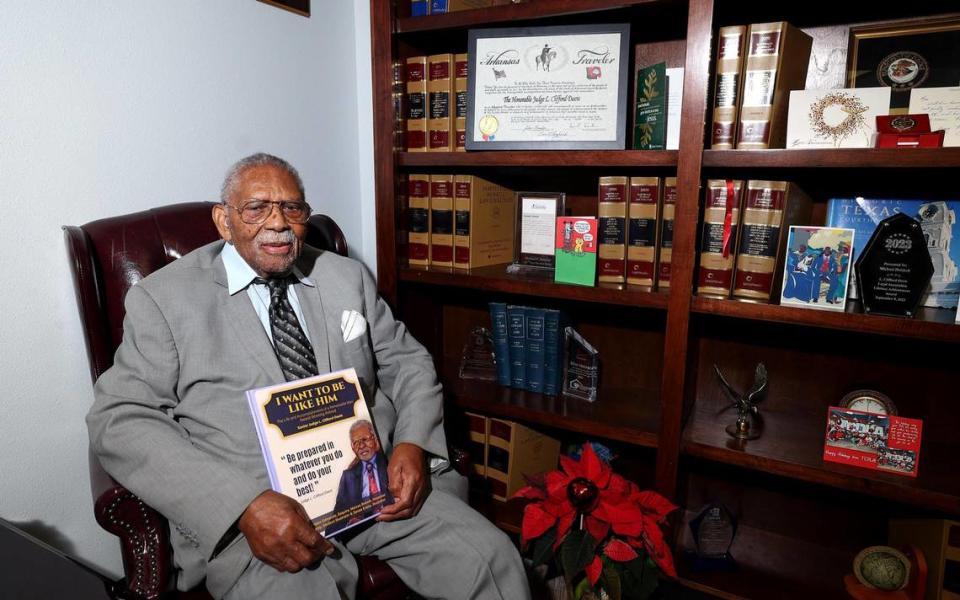

Judge L. Clifford Davis sits in his conference room, surrounded by mementos representing key events in a law career that spans more than 70 years.

In one corner there is a framed picture celebrating the 30th anniversary of the Brown vs. Board of Education Supreme Court decision, which said that the racial segregation of public schools was unconstitutional. Davis assisted on the case.

Underneath the picture is a glass container with a Children’s Gift Award that was presented to Davis to recognize lawsuits he filed to integrate the Fort Worth and Mansfield school districts. Yellow and blue medals hang on top of the glass, marking his 50th class reunion from the Howard University School of Law.

Davis, 99, opened one of the the first African-American law offices in Tarrant County and was one of the first Black district judges appointed in Tarrant County.

He sits back in his seat and says the fight for civil rights is important, but we must also emphasize civil responsibility. It is the responsibility of the people of the United States to treat all people with decency, respect and integrity regardless of race, sex, sexual orientation, or religion, he says.

“I’ve tried to live that, and I finally developed that into a philosophy, which I call my sermon,” Davis said. “I am proud of it, and I’m going to die with it.”

Davis has lived a good, long life, he says. He eats three meals a day, has no constant pain, tries to be courteous to everyone every day, and has no enemies, he says.

What makes his life extraordinary are his accomplishments in Texas and Arkansas. A local lawyer has even created a children’s book in his honor.

Life began on the family farm in Arkansas

Davis was born on Oct. 12, 1924, in Wilton, Arkansas. The youngest of seven children, he was raised on his family farm and received his early education in the Wilton school system. Davis’ family moved to Little Rock so the children could attend Dunbar High School and receive a better education.

In high school, Davis became interested in law through a civics class, which led him to study the constitution, government, and history.

He then went to Philander Smith College in Little Rock, where he graduated in 1945 with a bachelor’s degree in business administration.

Davis went to Howard University School of Law in Washington, D.C. , in 1945. He had applied for admission to the University of Arkansas in 1946, but was rejected because of segregation policies. Finances prevented Davis from returning to Howard, so he attended Atlanta University to pursue a master’s in economics. He returned to Howard in the fall of 1947, and shortly after received notification from the University of Arkansas School of Law, saying that if he applied and paid tuition in advance he would be accepted.

Davis did not want to pay in advance since others did not have to do so, and he rejected the offer.

In school he became acquainted with a prominent Arkansas lawyer named Scipio Africanus Jones. Jones was a self-taught attorney whose most famous case was defending 12 Black men sentenced to death following the Elaine Massacre of 1919 in Arkansas. Jones would later help Black law students gain admission into University of Arkansas School of Law.

“There’s a great emphasis on education and trying to improve life in the Black community and trying to get a career to make a good living and comfortable living for yourself and be a good citizen in the community,” Davis said. “That was emphasized both at the high school level at Dunbar as well as emphasized at Philander Smith College.”

Graduate of Howard University School of Law

He graduated from Howard Law School in 1949 and passed the bar in the same year. He returned to Arkansas to join a law firm with William Harold Flowers, one of the leading figures in the civil rights movement in Arkansas in the 1940s. Flowers’ firm was known for training and preparing law students for civil rights advocacy.

Wanting to be involved in a larger community, Davis moved to Waco where he taught two years at Paul Quinn College, which is now located in Dallas. In 1953, he passed the bar in Texas and became one of only two Black lawyers in Fort Worth.

In the spring of 1954, two lawyers from Dallas, C.B. Buckley and Louis A. Beckford, joined Davis to establish one of the first Black run law firms in Tarrant County. The firm’s most prominent cases involved the desegregation of school districts in North Texas.

During this time period, anyone in civil rights work coordinated with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, especially with the national office, Davis said.

Their law firm assisted attorney Thurgood Marshall of the NAACP (later a Supreme Court justice) on the case that would ultimately be Brown v. Board of Education (1954). Marshall helped the Texas branches of the NAACP, which were accused by the state of filing too many meritless lawsuits.

Davis and his law firm filed integration lawsuits in Mansfield, with Jackson v. Rawdon (1955), and in Fort Worth, with Flax v. Potts (1962). Each resulted in the desegregation of the districts.

Davis said the suits had a common theme.

“You did it with any other litigation with the intent to try to achieve, make life better for, and make opportunities better for Black people,” Davis said. “You were diligent, and you prepared to advance our community.”

When the Tarrant County Bar Association began accepting Black lawyers in the early ‘60s, Davis and two other Black lawyers decided against joining. They did not want to be in the situation where the bar would like some Black lawyers but ignore others.

Davis and 13 other African American attorneys helped create the Fort Worth Black Bar Association in 1977. In 1991, the name was changed to Tarrant County Black Bar Association, and in 2012 the name was changed to The L. Clifford Davis Legal Association.

Among first Black district judges Tarrant County

In 1983, Gov. Mark White appointed Davis to a judgeship in criminal district court, making Davis one of the first Black district judges appointed in Tarrant County. After losing his seat in 1988, he continued as a visiting judge until his retirement in 2004.

In 2002, the Fort Worth Independent School District built Clifford Davis Elementary School in honor of Davis.

Bobbi Edmonds is a local attorney who arrived in Fort Worth in 1987. She met Davis when she was practicing criminal law. She admired his fairness in court and the courteous manner he had with everyone he interacted with outside of court.

She began to research him and his accomplishments. In 1994, Edmonds helped arrange a portrait hanging ceremony in the Criminal District Court in honor of Davis. Since then, she has worked to recognize Davis whenever she could.

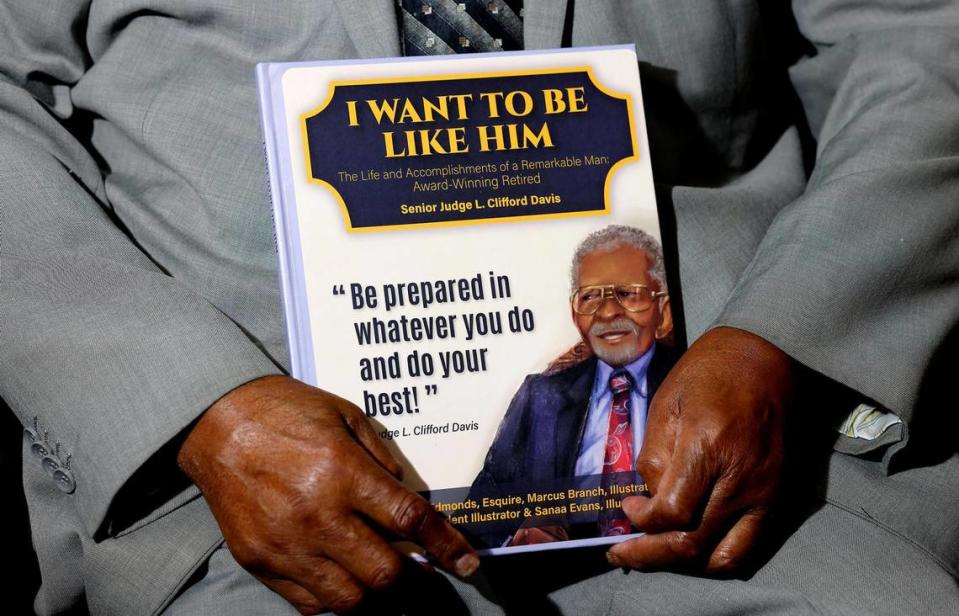

On Sept. 8, she released a book called, “I Want to be Like Him: The Life and Accomplishments of a Remarkable Man: Award-Winning Retired Senior Judge L. Clifford Davis,” in honor of Davis.

She describes her book as not just a children’s book but a family book for people to read to their children and for senior citizens to learn from Davis’ wisdom.

“We’re going to share his philosophy, to share his plight, that it may encourage and motivate others to excel beyond,” Edmonds said. “Like he always says, ‘Education is the key to a world of opportunities,’ and he means that.”

Davis has won numerous awards, including the Tarrant County Bar Association’s Blackstone Award, the bar’s most prestigious honor, and a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Texas Lawyer, a multimedia publication focused on law news. Davis was inducted into the National Bar Association’s Hall of Fame and the Arkansas Black Hall of Fame and received an honorary doctor of law degree from the University of Arkansas in 2017.

His accomplishments and accolades aside, Davis said he wants to be remembered for serving others.

“I tried to help people and make life better,” he said. “I was not just out for Clifford Davis, I was out to help make life better.”