Forty Years After Conrad N. Hilton's Death, His Foundation Is Still Giving

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

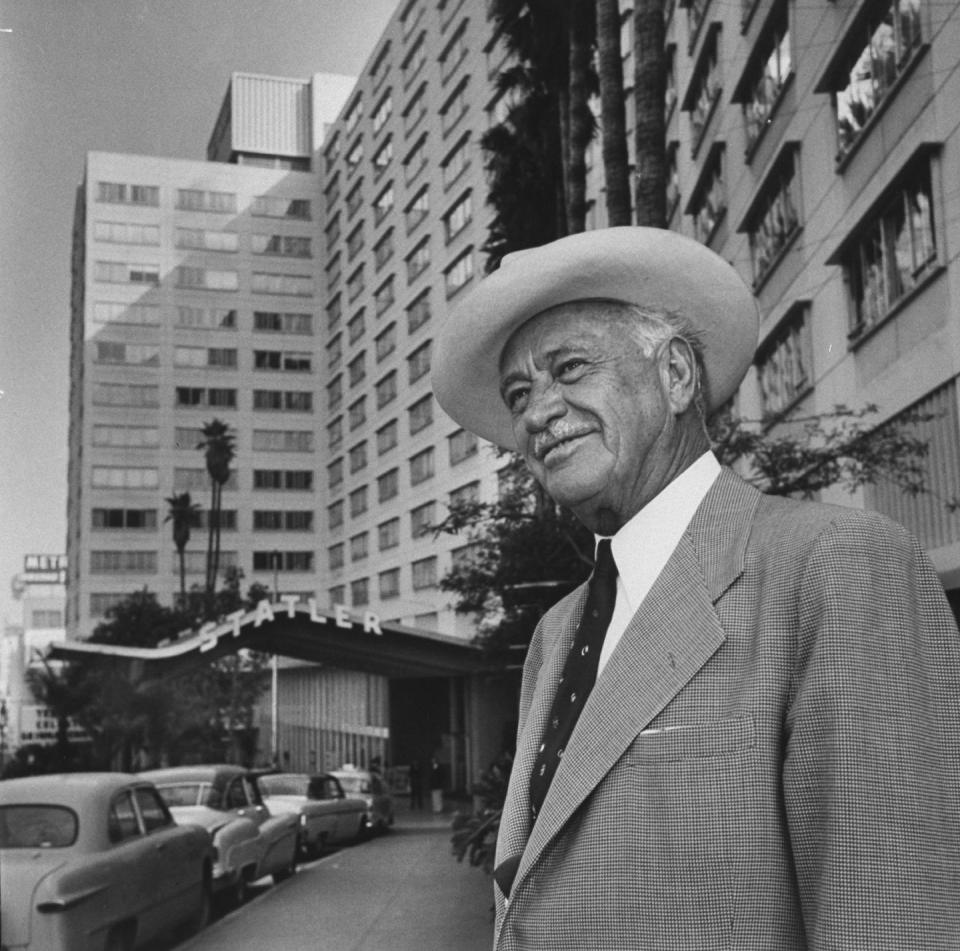

When he died in 1979 at the age of 91, Conrad N. Hilton—the founder of Hilton Hotels—left nearly all of his billion-dollar fortune to his namesake foundation, which he established in 1944. Forty years after Hilton's passing, the foundation continues to parcel out his largesse to worthy organizations around the world.

In addition to ongoing grants, each year the foundation selects one organization for special recognition with its Humanitarian Prize, which is the world’s largest annual humanitarian award. The Prize is presented to a nonprofit organization "judged to have made extraordinary contributions toward alleviating human suffering." To date, the Hilton Foundation has awarded $36.5 million to 24 recipients of the Prize.

This year, the 25th annual Humanitarian Prize will be given to Homeboy Industries, a Los-Angeles based organization that has become the world’s largest program for gang intervention, rehab, and re-entry. Founded in 1988 by Father Gregory Boyle, Homeboy Industries was formed with the goal of improving the lives of former gang members in East Los Angeles, who have been systematically marginalized even after they leave a gang.

The 18-month re-entry program focuses on helping participants heal from trauma and giving them paid employment opportunities in nine businesses that Homeboy Industries owns and operates, including a bakery and catering company, an electronic recycling company, and a silkscreen and embroidery shop. Homeboy also offers legal services, tattoo removal, a pathway to college educational program, and other social services.

With the Hilton award, Homeboy will receive $2.5 million in unrestricted funding. The virtual ceremony on October 23 will also feature panels with guest speakers, including Soledad O'Brien and Bryan Stevenson.

T&C spoke with the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation President and CEO Peter Laugharn about the 2020 award, the complicated state of philanthropy right now, and the foundation's goals for the coming year.

Your humanitarian prize this year is being awarded to Homeboy Industries. Why was it selected?

I think the prize jury was making a couple of points in the award. One: the issue of equity is really important. And this is a particular population that faces a lot of difficulties, in the road out of gang membership and out of prison.

The other point is about dignity. Yes, you can reform systems, but that has to include honoring and respecting individuals. If you go to Homeboy's headquarters, there is so much welcome. There is so much of looking people right in the eye and saying to them, "whether it was society as a whole or individuals, people have told you that you have no worth, no dignity, no future—and that is not true."

And I think that that is a really important part of Homeboy's message. And that message can be taken up directly by other organizations, right? Every nonprofit, every philanthropist, every local government official can pay more attention to what life is really like for people and how to make their lives better.

Philanthropy can often seem like it deals with far-away problems. But organizations like Homeboy are doing the work right here in one of the biggest cities in the U.S. It sort of brings it home.

Two of the values of the Hilton foundation are really exemplified in what Homeboy does: thinking big and compassion. Compassion is totally at the basis of what Homeboy does. It's saying "your wellbeing is important to me and I, as a citizen, have a responsibility to my fellow citizens, maybe not to all of them in the abstract, but there are things that I can do." And I think we've lost that a bit, especially in all the static and the noise going on in our society right now.

We see all the time, similarly to our work on homelessness, that when people come out of prison, they have very few options. They're given very little to start with and they will often end up on the streets. So I think whatever we can do to revive compassion is a great contribution to our problem solving ability and the cohesion of our society.

The "thinking big" part is to think about how that can be done on a wider scale and how that can reach more people. Homeboy, which is LA-based, has taken the show on the road. They have a global Homeboy network , they are in states all across the country, like Alabama and Idaho, but also abroad in Scotland, Guatemala. Most countries incarcerate a smaller proportion of their other people than we do, so while it may be more of an acute problem here, it is an issue everywhere that needs attention globally.

What do you think it means to be a philanthropist in 2020?

I think it is really important to aim your philanthropy at the long haul. A foundation like ours that's structured to exist in perpetuity has a longer horizon than government does within an electoral cycle, or than business with a business cycle, or nonprofits with a fundraising cycle. So I think foundations do their best work if they're keeping an eye on what's going to take five years or ten years to happen. That has been put to the test this year.

So how do you operate in a year like this?

We have been working at three speeds. The first, especially in March and April was "what immediately can we do to get ahead of Covid?" We did some of the fastest grant-making that we've ever done both in Los Angeles and in Africa. In LA it was to really help protect the homeless who would be one of the most vulnerable populations. And in Africa it was to help the World Health Organization help ministries of health across the continent to get ready for Covid.

The second speed was longer term coordination, especially with public health authorities to help them do their work. Some of that was funding directly to governments, which is not what we typically do, and some of it was funding nonprofits to work alongside government.

And the third speed was: when we start to come out of this, how do we review and strengthen public health approaches? We have an epidemic playbook and we should have been really well prepared for this crisis. I think we haven't performed to the level that we should have, and that's not only at a federal level, but also state and local, and also communities and individuals. So what has this experience taught us and how can we be better prepared next time?

What is one major problem facing American philanthropy?

I think the big challenge confronting American philanthropy today is just the enormity of the problems that we're facing. For one, there's climate change, and there are all sorts of questions about equity, but people have almost forgotten because of Covid as both public health and an economic crisis. So I think one thing is let's not forget our longer term goals and keep our eyes on the prize.

The other thing is the enormity of these challenges means there needs to be collaboration across sectors. You know, the simplest thing for a foundation to do is make grants to a nonprofit. And those are really important—we've done a lot of really good ones this year that we feel great about. But I think these problems need collaboration between government, the private sector, and nonprofits, and they need to be thoughtful about the strengths and weaknesses of each.

How is the Hilton Foundation helping to answer that call?

To take a municipal issue in Los Angeles as an example, when Covid hit, it was necessary to do a lot of things very quickly, and some of those are well done by government, and some are not. Getting PPE out to homeless people and to outreach workers was much better done by nonprofits who are already on the frontlines, on the ground. So that was where a lot of our early funding went—but the long-haul response is not a nonprofit response.

What issues are you focusing on as we head into 2021?

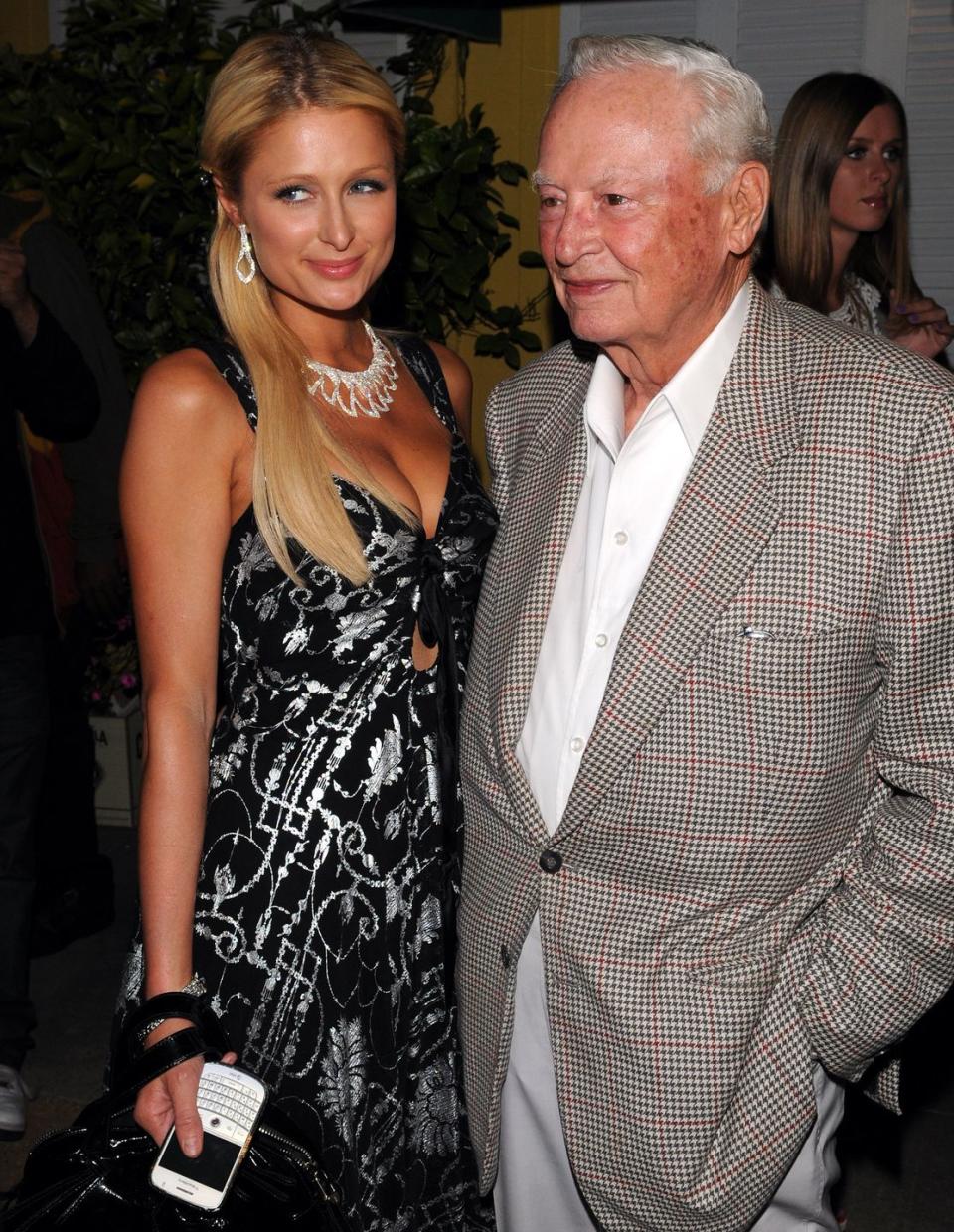

Last year, Conrad Hilton's son Barron passed away and left 97% of his fortune to the foundation. So we've doubled our asset base and therefore are going to double our grant making, and it will go up to about $280 million a year. About half of that will be domestic and about half international.

We will focus significant grants on issues related to children and youth, either early childhood or older youth from age 18 to 24. Catholic Sisters is in Conrad Hilton's will and is one of our largest programs that tends to focus on youth and families. We'll also be working on homelessness in Los Angeles and safe water in Africa.

What is one issue you think doesn't get enough attention in philanthropy?

I would say in general that we feel that children and youth could get a lot more attention. The level of child poverty in the United States could be significantly improved without a tremendous amount of outlay and again, not from philanthropy, but from the government.

Speaking of youth, how have you been inspired by young philanthropists?

Oh, I think there's much that's inspiring, right? I mean, we're in a generational transition. My assessment of young philanthropists is that they are clear-eyed about the challenges that are in front of us. There is strong problem solving and a "we need to tackle this" mentality rather than "well maybe we can live with it." It's not a complacent generation. There is new energy and a desire to make their generation's accomplishments on the road to a more equitable society, and one that's sustainable.

Click here to register for the ceremony of the 2020 Conrad N. Hilton Foundation Humanitarian Prize, which will be presented virtually on Friday, October 23 beginning at 10 a.m. Eastern.

You Might Also Like