Fossil reveals human ancestors butchered one another for reasons beyond ritual

Editor’s Note: Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

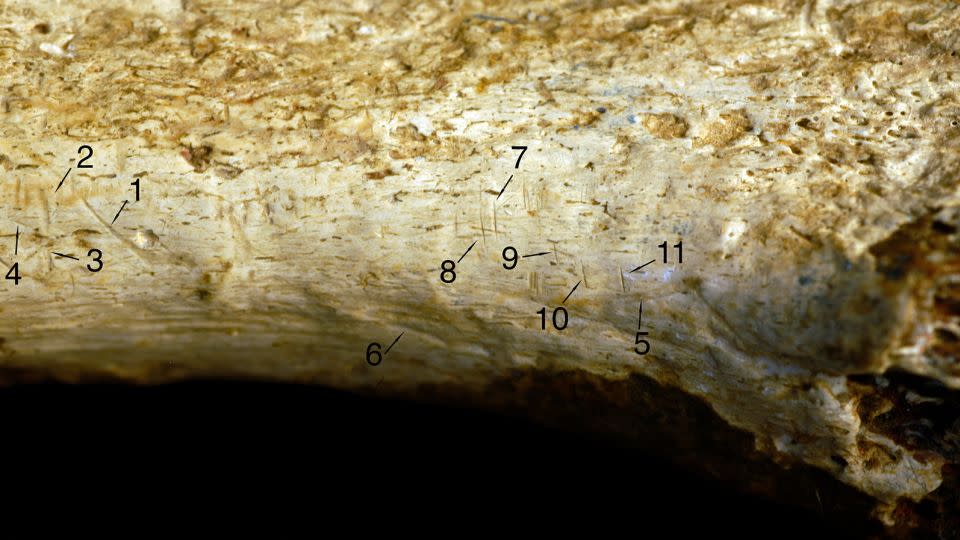

Nine cut marks on a fossilized shin bone suggest that ancient human relatives butchered and possibly ate one another 1.45 million years ago, according to a new study.

The fossilized tibia was found in the collection of National Museums of Kenya’s Nairobi National Museum by Briana Pobiner, a paleoanthropologist at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington DC.

Pobiner was studying the collection, looking for bite marks from extinct animals that might have preyed on ancient hominins, when she came across cuts that looked like they had been made by stone tools.

“These cut marks look very similar to what I’ve seen on animal fossils that were being processed for consumption,” Pobiner said in a news release.

“It seems most likely that the meat from this leg was eaten and that it was eaten for nutrition as opposed to for a ritual.”

What the cut marks reveal

Study coauthor Michael Pante, a paleoanthropologist at Colorado State University, created 3D models based on molds of marks on the bone. He compared the shape of the cuts with an existing database of 898 individual tooth, butchery and trample marks created during controlled experiments.

Pobiner had not told him she thought the cut marks were made by stone tools, but his analysis came to the same conclusion.

The cut marks are all oriented in the same direction, making it possible that a hand wielding a stone tool could have made the marks one after another without changing grip.

It’s not clear what species of ancient hominin the shin bone belonged to — because a leg bone doesn’t offer as much taxonomic information as a cranium or jawbone. The fossilized tibia was initially identified as Australopithecus boisei and then in 1990 as Homo erectus.

The emergence of sophisticated stone tools is linked with the emergence of the Homo genus that includes our own species, Homo sapiens, but more recent research has suggested that other ancient hominins may have used stone tools even earlier.

Hominins eating hominins

By themselves, the cuts do not definitively prove that the ancient human relative who inflicted the damage also made a meal out of the leg, but Pobiner said it was possible. The marks are located where a calf muscle would have been attached to the bone — a good place to cut if the aim was to remove flesh.

“The information we have tells us that hominins were likely eating other hominins at least 1.45 million years ago,” Pobiner said.

“There are numerous other examples of species from the human evolutionary tree consuming each other for nutrition, but this fossil suggests that our species’ relatives were eating each other to survive further into the past than we recognized.”

Silvia Bello, a researcher in human origins at London’s Natural History Museum, said that cannibalism might have been more common in the past than previously thought, noting that evidence for the behavior had also been found at archaeological sites associated with Neanderthals and early modern humans.

For example, Neanderthals living 100,000 years ago in what’s now France practiced cannibalism, perhaps because a warmer climate made food harder to come by.

The latest study, published Monday in the journal Scientific Reports, is “significant because this new find suggests that cannibalism might have been practiced, at least occasionally, a long way back in our ancestral history,” said Bello, who was not involved in the research.

Her colleague Chris Stringer, research leader in human origins at London’s Natural History Museum, said the shin bone was probably not the oldest known example of human relatives butchering one another. He said cut marks were reported on the cheek bone of a hominin fossil found in Sterkfontein, South Africa, in 2000 that could be about 2 million years old. Pobiner, however, said the source of the cut marks in that case was disputed.

“This new evidence looks quite convincing and adds to the evidence for cannibalism in very early, as well as the considerable evidence from later, humans,” said Stringer.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com