New fossils reveal specialized eating technique of unusual ancient marine reptile

Editor’s Note: Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

An unusual ancient marine reptile may have gulped down tons of shrimplike prey using a feeding technique similar to one used by some modern whales.

The reptile, named Hupehsuchus nanchangensis, lived in Earth’s oceans between 247 million and 249 million years ago, during the early Triassic Period.

Fossils of the reptile were first found in China in 1972. But researchers have struggled to understand the animal’s feeding behavior and lifestyle because none of the skulls were well preserved.

Two newly discovered fossils unearthed from China’s Jialingjiang Formation in Hubei province include the nearly complete skeleton of one reptile and a large portion — from head to collarbone — of another.

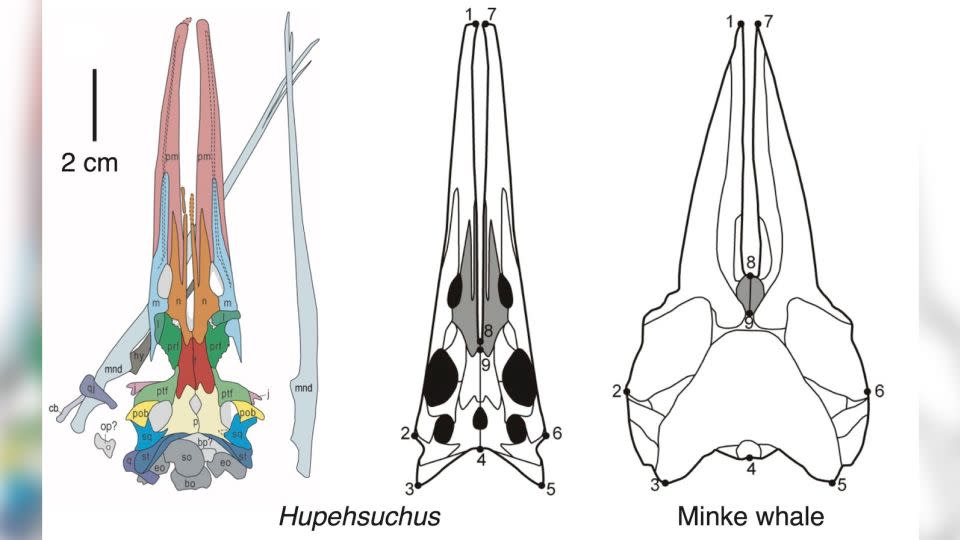

The discoveries enabled researchers to take a closer look at Hupehsuchus nanchangensis and determine that the reptile had a toothless snout and a small, narrow skull. Its lower jaw was loosely connected to the rest of the skull, which means the creature could expand its mouth — similar to how modern whales eat by filter feeding.

A study detailing the findings was published Tuesday in the journal BMC Ecology and Evolution.

“These were more complete than earlier finds and showed that the long snout was composed of unfused, straplike bones, with a long space between them running the length of the snout,” said study coauthor Long Cheng, professor at the Wuhan Center of China Geological Survey, in a statement. “This construction is only seen otherwise in modern baleen whales where the loose structure of the snout and lower jaws allows them to support a huge throat region that balloons out enormously as they swim forward, engulfing small prey.”

Fossil evidence of filter feeding

Researchers compared the Hupehsuchus skull with 130 modern skulls from a range of aquatic animals, which included 23 seal species, 14 crocodilians, 52 toothed whales, 25 birds, the platypus and 15 species of baleen whale. The study team discovered the creature had the most in common with the baleen whales.

Modern bowhead and right whales are species that use filter-feeding techniques to eat, sifting material through plates of baleen as they swim with their mouths open near the ocean’s surface to take in large quantities of plankton or small crustaceans called krill.

“Baleen is made from keratin, forming a soft and tough fibrous curtain dangling from the upper jaw in baleen whales,” according to the study. During filter feeding, the sturdy baleen plates entrap prey as water is forced out.

But there hasn’t been much evidence in the fossil record for ancient reptiles using filter feeding, until now. While no actual evidence of baleen was found in the Hupehsuchus skull, the researchers noticed a series of grooves around the roof of the mouth where soft tissue may have helped with filter feeding. These structures are similar to what’s seen in baleen whales, which have strips of keratin instead of teeth.

“Modern baleen whales have no teeth, unlike the toothed whales such as dolphins and orcas,” said study coauthor Li Tian, assistant researcher at the China University of Geosciences Wuhan, in a statement.

“Baleen whales have grooves along the jaws to support curtains of baleen, long thin strips of keratin, the protein that makes hair, feathers and fingernails. Hupehsuchus had just the same grooves and notches along the edges of its jaws, and we suggest it had independently evolved into some form of baleen.”

Hupehsuchus and evolutionary revelations

Hupehsuchus had a rigid body that caused it to be a slow swimmer, so the reptile likely expanded its throat while swimming to take in big gulps of water, straining out shrimplike prey from the early Triassic oceans. It’s possible that the marine reptile didn’t start out with this ability. Instead, the creature may have evolved over time, developing the adaptive physical traits that enabled filter feeding if the competition level for food was high, according to the study.

The discovery is an example of what scientists call convergent evolution, where similar features evolve independently in different species.

“We were amazed to discover these adaptations in such an early marine reptile,” said lead study author Zichen Fang at the Wuhan Center of China Geological Survey, in a statement. “The hupehsuchians were a unique group in China, close relatives of the ichthyosaurs, and known for 50 years, but their mode of life was not fully understood.”

Whales evolved about 15 million years after dinosaurs went extinct at the end of the Cretaceous Period 66 million years ago. And it took about 17 million years for whales to evolve their filter-feeding adaptations, according to the study.

But this same technique was quickly adapted, within about 5 million years, by marine reptiles that lived much earlier than whales.

“The hupesuchians lived in the Early Triassic, about 248 million years ago, in China and they were part of a huge and rapid re-population of the oceans,” said study coauthor Michael Benton, professor of vertebrate palaeontology in the University of Bristol’s School of Earth Sciences, in a statement. “This was a time of turmoil, only three million years after the huge end-Permian mass extinction which had wiped out most of life. It’s been amazing to discover how fast these large marine reptiles came on the scene and entirely changed marine ecosystems of the time.”

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com