Foster kids starved, beaten and molested, reports show. Few caregivers are punished.

A cache of documents pried loose after USA TODAY’s investigation in October into Florida’s child welfare system reveals allegations of foster care abuse are more widespread than previously reported.

The nearly 5,000 records detail calls to the Florida Department of Children and Families abuse hotline from teachers, health care professionals, day care workers, neighbors and others about the treatment of kids in state care.

None of these cases would have been counted in what Florida publicly reports each year about the number of serious abuse, neglect and abandonment allegations in its foster care system.

DCF said the accusations do not meet its definition of serious harm. Instead, they are classified as foster care “referrals,” potential license violations that may prompt an administrative review and that Florida officials fought to keep secret for years.

The records obtained by USA TODAY include calls that accused foster parents and group home workers of hitting children with hands, belts and household objects; denying them medical care and sending them to school dirty, hungry and dressed in ill-fitting clothes.

They complained of empty pantries and padlocked refrigerators, of children who lived in rodent-ridden homes and ate cereal crawling with ants. One caller described a girl’s face and body covered in sores, dripping fluid down her arms that stuck to her clothes. Another caller alleged that a group home staff member gave a gay foster child literature that called for the execution of homosexuals.

“Like everything else in child welfare, determinations of ‘abuse’ and ‘neglect’ are arbitrary, capricious and cruel,” said Richard Wexler, executive director for the National Coalition for Child Protection Reform.

There is no federal standard for what constitutes abuse, leaving each state to craft its own criteria. Narrow definitions can lower the number of abuse investigations, Wexler said.

As USA TODAY’s six-part series revealed, state lawmakers rewrote rules in 2014 to make it easier to seize children from their parents, but they had no plan for where to house the growing numbers. As a result, caseworkers placed kids in dangerously overcrowded homes and with foster parents who later faced civil or criminal charges of sexual assault and torture. Nearly 200 boys and girls were sent to live with foster parents on whom the state had some evidence that abuse had occurred.

USA TODAY requested foster parent disciplinary records in 2019, but DCF officials and executives in charge of nonprofit groups that run the child welfare system on the local level either denied access or demanded tens of thousands of dollars in search and copy fees.

In January, a government official who asked not to be identified provided reporters with foster parent reprimands, license revocation notices and a spreadsheet of 4,300 abuse hotline complaints involving foster and group homes. USA TODAY spent six weeks reviewing the documents.

The review shows:

The number of foster care referrals filed against foster parents, group homes and guardians rose by roughly 54% over the past five years, from fewer than 700 complaints in 2015-16 to more than 1,000 last year.

DCF revoked or refused to renew only 29 caregivers’ licenses over the same five-year period, records show, and USA TODAY was provided with just 58 corrective action plans in which foster parents agreed to take training courses and accept additional monitoring to retain their licenses.

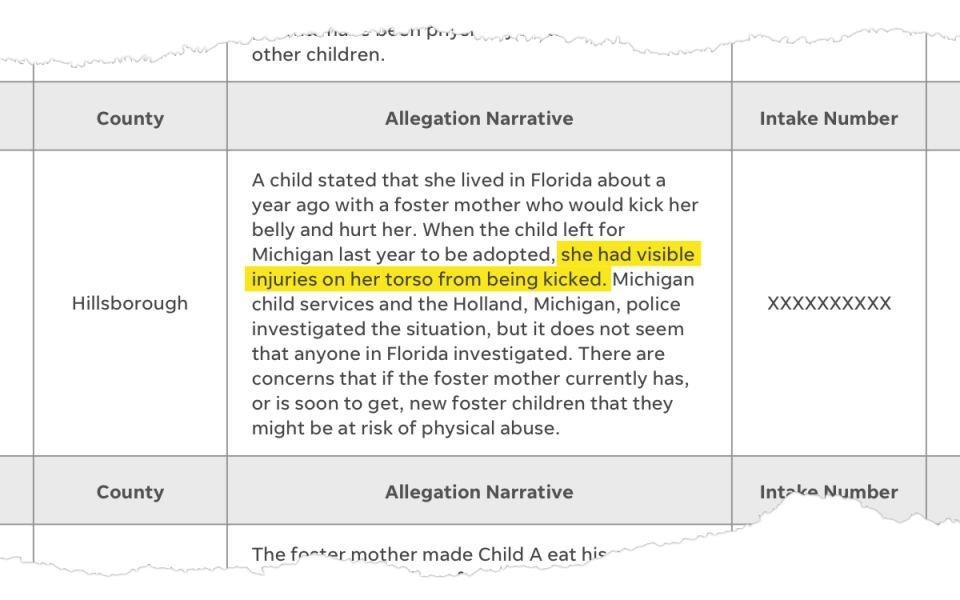

DCF policy expressly forbids cruel and unusual disciplinary methods as well as corporal punishment, which includes spanking, hitting, slapping, pinching or shaking. It’s not clear that DCF is enforcing that policy, given the small number of cases that end in official action. At least 15% of the foster care complaints – involving more than 750 children – accused caregivers of such methods. Others reported physical abuse: One caller said that when a child left Florida to be adopted in 2016, she had visible injuries on her torso from being kicked in the stomach by her foster mother.

Children and others accused foster parents in more than 100 cases of molestation and violating kids’ personal space or privacy, watching them as they showered or changed clothes. Callers made 65 complaints that caregivers did not adequately supervise sexually abused children to ensure they did not abuse other kids. These, too, were labeled as potential license violations.

Though the agency pays foster parents to keep kids safe and provide for their needs, more than 800 foster care referrals feature some form of neglect. A Leon County girl said she prostituted herself via internet ads to earn money “because she stated she isn’t provided with enough food and clothes in the foster home.”

Given two weeks to answer detailed written questions about the allegations, including how many were confirmed and whether DCF had taken action not reflected in documents made available to USA TODAY, the agency did not respond. Documents obtained by USA TODAY do not indicate how DCF followed up on the thousands of complaints concerning children, except that they were considered serious enough for additional scrutiny.

After reviewing 25 randomly chosen complaints, Wexler said at least 16 would have constituted abuse or neglect if they had been made against biological parents. In seven of them – had they been verified – the children would have been removed on the spot. It’s not clear from DCF’s records if any of these complaints were among the fewer than 100 cases that resulted in documented action against foster caregivers.

About the series

This is an ongoing series about Florida’s child welfare system, which has taken an increasing number of kids into foster care without enough safe places to put them and has blamed victims - mostly mothers - when their children witness domestic violence. Reporters at USA TODAY spent more than a year analyzing data and interviewing families, insiders and advocates, revealing how overwhelmed state officials put nearly 200 children into the arms of abusers and how the system is stacked against battered women.

Contact the reporters

Pat Beall, pbeall@gannett.com

Michael Braga, mbraga@gannett.com

Daphne Chen, dchen@gannett.com

Suzanne Hirt, shirt@gannett.com

Josh Salman, jsalman@gannett.com

“If they are classifying these as mere referrals, then it reveals a dangerous double standard concerning what constitutes abuse by a birth parent compared to what a foster parent is allowed to do,” Wexler said.

Other child experts and dependency court attorneys who reviewed the documents confirmed that the complaints were representative of the kinds of abuse and neglect that would get children removed from their biological parents.

“This is stuff kids tell you about when foster homes are really bad,” said Robert Latham, a child advocate and clinical instructor at the University of Miami’s law school.

Even critics of Florida’s child welfare system acknowledge that foster parents, asked to care for troubled children with financial support amounting to just $15 a day per child, face a daunting task.

Before entering state care, about 15% of children had been physically or sexually abused, according to Child Trends, a Maryland-based child research group. Many live with autism, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), post-traumatic stress disorder, depression or schizophrenia. Still others are nonverbal, developmentally delayed, incapable of feeding themselves and in need of constant care and supervision.

The records USA TODAY obtained describe children who screamed for hours, threw tantrums, smashed windows and destroyed home decor. One alleged a child hurled a hot iron at a foster mother. Another reported that a girl pushed her 6-year-old sister’s head into a wall and snatched a Taser from a police officer who responded to a call for help.

“The overwhelming majority of foster parents are good people who provide loving, caring homes for children in desperate need. And I am so grateful for those families,” said state Sen. Lauren Book, a Plantation Democrat who chairs the Children, Families and Elder Affairs Committee. “But when it comes to children’s lives, we simply cannot settle for an ‘overwhelming majority’ – we need to do more to make sure that children in the system are in safe homes ... period.”

During a meeting in January with the committee in Tallahassee to discuss USA TODAY’s Torn Apart series, DCF Secretary Chad Poppell acknowledged that his agency had done a “bad job” caring for kids.

“I won’t belabor the point, the quality of the work was poor,” Poppell said. He promised to establish specialized teams to investigate foster care abuse allegations and to review the agency’s decisions in those cases.

Poppell has since resigned, and Shevaun Harris was named to fill the position. Harris did not comment for this story. Instead, DCF released a statement noting that over the past two years, it has strengthened its oversight of the child welfare system and that Florida has seen a general decline in the rate of abuse and verified maltreatments in out-of-home care since 2015.

“Often the cases that are written about in the news are not the norm,” DCF said. “Our child welfare leaders have been working to bring meaningful change to the child welfare system and the care children receive. Any narrative indicating otherwise is simply false, and ignores the truth of what has been unfolding across the state.”

System favors foster parents

Abuse investigations start with a phoned, faxed or online report of suspected harm to the Florida Abuse Hotline. A hotline counselor speaks with callers, reviews submitted information and decides whether the allegation of abuse, neglect or abandonment is serious enough to warrant a child protection investigation.

If there is an allegation involving foster care that the counselor does not believe rises to DCF’s criteria for serious abuse or neglect, the counselor has the option of classifying the complaint as a referral – a potential foster license violation, according to DCF. Referrals can grow into abuse investigations. But for the most part, licensing specialists or caseworkers, not child protection investigators, handle referrals.

In at least four counties, the same case manager assigned to complete regular visits to the foster home where the abuse reportedly occurred is often dispatched to investigate the allegation, former DCF attorney Lisa Dawson-Andrzejczyk said.

“The vast majority of case managers are good and dedicated and appreciate the seriousness of their job, but you’re going to have some who didn’t do the home visits, or they visited the child at school and called it a home visit,” Dawson-Andrzejczyk said. “They have every reason to not want to acknowledge that there’s something they might have missed.”

When the department investigates foster care referrals, Wexler said, “DCF is, in effect, investigating itself – since it was DCF whose actions put the child into foster care in the first place.”

Every state has its own criteria for serious abuse. DCF’s child maltreatment guidelines say that failing to provide children with clean clothing, treat their cavities, give them ADHD medicine or pick them up from school on time is not always neglect if it doesn’t create a safety or health threat. Though corporal punishment is prohibited, the agency does not necessarily consider it physical abuse.

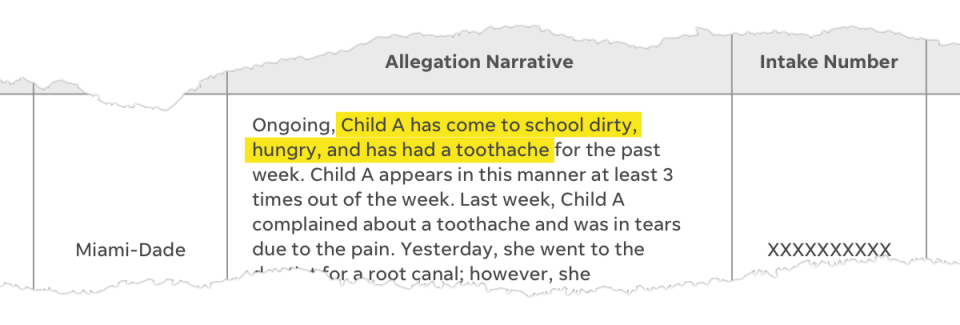

So although an emotionally disturbed Miami-Dade girl reportedly came to class dirty and hungry at least three times a week in 2018, wearing ill-fitting sneakers and a jacket with a hole, that was not automatically neglect. When emergency room personnel complained that caregivers dropped off kids and did not return and schools reported foster parents refused to pick up students, or even answer phone calls, that was not necessarily abandonment.

DCF classifies such complaints among less urgent issues that a licensing specialist can assess and help resolve, in some cases, with a corrective action plan. The number of these reports that DCF does not consider abuse or neglect – despite the serious allegations some contain – has surged over the past five years. But records supplied to USA TODAY show licensing revocations haven’t.

The department confirmed “some indicators of abuse” in one Miami foster home as early as 1996 and 2000. Both times, child welfare agencies greenlit the Miami pastor and his wife for relicensing, records show.

In July 2013, a 5-year-old being watched by the foster mother was reportedly sexually molested. Two months later, a former foster child said the couple’s adopted son had repeatedly raped him “for years.”

DCF did not revoke the foster license this time either.

Instead, caseworkers implemented a corrective action plan: The couple could have just one young foster child. Their adopted son could still be around other children as long as he was carefully supervised.

The foster mother was angry about the accusations, believing her adopted son incapable of the actions attributed to him, the documents say, but she accepted the corrective plan.

When asked for disciplinary actions taken against foster parents over the past five years, DCF provided just 29 license revocations and 58 corrective action plans. It declined to say whether that was the full extent of corrective action plans implemented during the period.

A system desperate for foster parents will let a lot of things slide, said Neil Skene, who served as DCF’s special counsel from 2008 to 2010 and chief of staff at the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services from 2015 to 2017.

Rather than confront foster parents and close foster homes, DCF and its private contractors can sideline caregivers in other ways.

“We had a sort of ‘do not call’ registry for problematic foster parents,” Skene said. “We didn’t revoke their licenses, we just didn’t send them any more kids.”

Removing children from the home can be faster than revoking a foster home license.

DCF does not always have the authority to withhold issuing a foster home license if one of its private contractors attests that a foster home is appropriate. Revoking or refusing to renew a license can lead to drawn out legal challenges by foster parents.

In 2018, for instance, DCF revoked a foster mother’s license in part because she used a “full nelson” wrestling hold on a troubled preschooler even after being warned not to, cursed at the child and joked about giving the girl Benadryl to make her “calm her butt down and pass out,” records show.

The woman appealed, sayng she had repeatedly asked a DCF subcontractor how to safely hold the child during a tantrum. A judge ruled in her favor, finding that DCF lacked evidence to support its allegations.

The small number of disciplinary actions is in no way commensurate with the kind of abuse and neglect that seems to be prevalent in the system, critics said.

“The fact that we only revoked 29 licenses is an atrocity,” Sen. Book said. “It’s unacceptable for children to be taken from their families and put in places where they are in more danger.”

Spanked for wetting the bed

DCF policy requires caregivers to discipline with kindness and consistency, using positive reinforcement or expressing verbal disapproval, but never with physical force.

“Corporal punishment of any kind is strictly prohibited because children who have been removed from their own parents due to abuse and neglect are particularly vulnerable,” a DCF official wrote in a letter informing a foster parent that her license would not be renewed because of a violation of agency policy. The department considers corporal punishment to be “among the most serious offenses by a foster parent,” the letter said.

Yet nearly 900 of the records USA TODAY obtained describe some type of physical abuse or corporal punishment – including spanking, hitting, slapping, pinching or shaking. At least 16 complaints accused foster parents of doling out physical discipline for bathroom-related accidents.

“Spanking is an ignorant way to respond to a child wetting the bed or any kind of toileting accident,” said Thomas Dikel, a Gainesville pediatric neuropsychologist. “To spank them or hit them or any kind of corporal punishment is going to have an amplified effect on a child who has been traumatized.”

Callers accused adults of striking their foster children with belts, rulers, hands and hairbrushes. Children reportedly were smacked on the buttocks, hands and legs or slapped across the face. They were spanked for wetting the bed, crying too loud or too long, moving too fast or too slow, for making poor grades, losing insignificant items or forgetting trivial information.

“There’s a zero-tolerance policy for corporal punishment until it has to be applied,” said Latham, the child advocate and University of Miami law instructor. “The system has an incentive not to believe children because it’s afraid to lose foster parents. Even calling in abuse reports is frustrating because you’re almost sure nothing is going to happen.”

Cruel or unusual punishment, though also expressly forbidden, appeared in more than 20 complaints. Several bordered on the bizarre.

A Volusia County woman was twice accused of forcing her foster children to stay in their room facing the wall all day and slapping them if they leaned on it for support. One of the kids said the woman made him eat a graded school paper and called him a failure, according to the allegation. The boy’s sibling had marks on his legs that the foster mother said were bug bites; the children said they were burns.

Reports accused caregivers of ordering kids to do pushups, planks and wall sits as discipline; to stand in rice and do squats or on one leg with hands raised until they cried; to hold heavy objects in the air. At a St. Johns County group home, a staff member reportedly restrained a boy, put him in a shower in view of other residents and cut off his clothes with scissors while the boy cried and covered his privates.

“What kind of human being makes a child stand in rice with a book over their head?” said Book, the state senator who champions reform legislation. “That’s torture.”

Disturbing behaviors

Dozens of foster care referrals implicated foster parents and their adult children or friends in sexual misconduct.

A Pinellas County foster father who took a polygraph test when he applied for a sheriff’s office job allegedly admitted to being aroused by children and “failed miserably” on sexual deviance questions.

Another foster father reportedly told a therapist that although he did not ask his foster daughter to sexually grope him while sleeping in his bed, he did not stop her. A Putnam County girl said her foster father slept with her in her bed on Friday nights because she must have done something wrong. A man reported his former foster father’s friend and co-worker molested him for two years, sending him gifts and $3,000 to keep quiet.

Not all sex-related allegations involved assault.

Reports repeatedly accused foster parents and group home staffers of walking in on teenagers showering, staring at and even touching their genitals. One man allegedly watched his foster daughter play during recess at the school where he taught, gazed at her through her classroom door and insisted she sit with him alone in the morning so constantly that the school switched her lunch schedule so she could have time free from him.

A hospital obstetrics team reported that a pregnant girl with an IQ of 72 in an extended foster home for older, vulnerable foster teens and young adults visited the medical facility twice in seven days for unexplained vaginal bleeding. Hospital personnel expressed concern that the foster mother’s adult son and his friends were going into her bedroom at night.

Child welfare workers often craft safety plans for sexually abused or aggressive children that require extra supervision or bedroom door alarms. Yet in multiple cases involving younger children, safety plans allegedly failed or were never adopted, allowing children to molest other foster kids.

Lack of food, medical neglect

DCF cites neglect in roughly four of 10 cases in which it removes children from their biological parents. Yet the same issue arises in foster homes: Approximately 850 foster care referrals over the past five years alleged medical neglect, inadequate housing or lack of food, clothing or hygiene.

None met the formal criteria to trigger an investigation, according to DCF, and instead were treated as licensing issues.

More than 80 hotline complaints described overcrowded and filthy foster homes where air conditioners were broken or unused and children said they slept on mattresses or floors rather than in beds. A sister and brother told an adult they were not allowed to bathe on weekends because their foster mother said the water bill was too high.

Withholding food was a repeated concern. When a licensing agency ordered one Brevard foster mother to remove a lock from her refrigerator, she replaced it with a bell, a complaint alleged. Another said a Suwanee woman would not feed her foster children at home in the evening because they “already ate” breakfast and lunch at school. One girl was removed from the home because of the report.

More than 30 callers reported children were locked out of homes because no one was available to care for them until late in the evening. Some said foster parents shut children outside as punishment and left them without food or access to a bathroom.

Schools and day care centers reported in detail that children attended classes day after day in the same soiled clothes. One girl arrived in pants so small she couldn’t button or zip them. The school provided her another pair, the caller said. Others had no underwear.

Nearly 200 callers complained of medical neglect, including cases where child welfare workers dropped off children at foster homes without informing caregivers of the kids’ medical needs. A diabetic child fell critically ill as a result, one caller reported. Another said a foster mother learned from caseworkers that a child needed medication for mental illness only after the girl threw a tantrum and threatened to kill her.

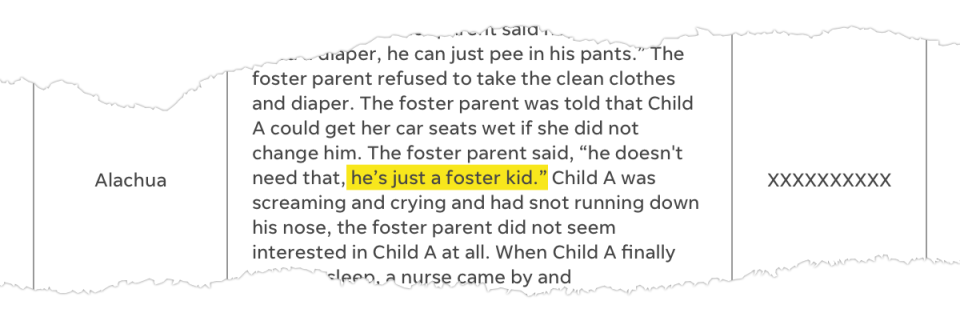

Health care workers reported foster parents who were indifferent to a child’s suffering in multiple cases. One caregiver brought a small boy to the emergency room, then refused to take him to the bathroom, according to a detailed complaint. He cried and “peed on himself and all over the floor.” A nurse brought him fresh clothes, but the foster mother said he didn’t need a diaper, could “pee in his pants" and was “just a foster kid.” When the boy fell asleep, a nurse commented on how cute he looked. “Good, you take him home,” the woman reportedly said.

Other complaints described caregivers failing on even more basic levels: An Orlando-area group home staff member found a foster child who had attempted suicide by hanging, one caller said. The staffer panicked and told another foster girl to check whether the child was alive. The girl complied, removing a belt from the dead child’s neck. She developed PTSD, began dissociating and became resistant to counseling.

Welcome changes

Poppell said he agreed with key points of USA TODAY’s series and successfully pushed for bills creating more accountability for how foster children are treated. Since that legislation passed last year, DCF said in its statement, “We’re deploying fixes immediately when issues arise, implementing uniform, outcome-based metrics to more closely monitor both internal and outsourced operations, and establishing graduated provider sanctions for poor performance.”

At least seven child welfare bills addressing foster care are winding through state Senate and House committees in this year’s legislative session. One of the most sweeping, if passed, could pave the way for children and their biological parents to have free legal counsel. It would make one of Poppell’s policy proposals law: requiring the state’s Critical Incident Rapid Response Team, which investigates child deaths when there was a recent abuse finding, expand its investigations to include sex abuse.

The investigating team would include a representative from a child advocacy center with expertise in child sex abuse. The legislation would mandate “immediate” investigations and require that certain lawmakers have access to abuse records. It calls for more support for foster parents.

Such changes would be welcome, said Wexler, the child advocate, but Florida needs to address the shortage of good foster homes – or risk exposing children to worse treatment within a system that can’t afford to hold bad caregivers accountable.

“A foster-care panic ratchets up the pressure to lower standards for foster homes and to ignore abuse in foster care,” Wexler said. “A foster-care panic leaves agencies begging for beds, and beggars can’t be choosers. So there is an enormous incentive to see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil and write no evil in the case file.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Foster care children starved, beaten, molested, Florida reports show