He fought 16 years to prove innocence in murder case. A Miami judge changed his life

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Emmanuel Jean is a free man. It’s the first time in 16 years he could say that.

At 23, he was sentenced to life in prison for murder. He maintained his innocence from the time he was arrested — a declaration that few paid attention to until a Miami judge reversed his conviction years later.

In July 2006, Jean was arrested after being accused of gunning down and robbing a shopkeeper in North Miami Beach. Mohammad Ayoub, a 60-year-old Saudi Arabian immigrant and father of four, was shot in the head that May after a struggle.

Ayoub had moved to the U.S. five years earlier and opened a convenience store. He was murdered just weeks before he was to be sworn in as a U.S. citizen.

A rogue cop. Pressured witnesses. A tumultuous history with police. It all conspired to bring Jean down.

Now, he’s back up.

After years of appeals, Jean’s name was cleared in April by Miami-Dade Circuit Court Judge Miguel De La O. The evidence in his case was weak: no gun, no DNA, no surveillance video.

The only physical evidence, a partial palm print on the store’s push bar, was tied back to Jean, though he frequently visited the neighborhood store. The crime scene technician brought to the stand during Jean’s trial, however, couldn’t indicate when the print was made.

Jean was released on April 29 — his 36th birthday — after striking a deal with the state and pleading guilty to conspiracy to commit robbery. His life sentence was reduced to five years, and then he was immediately released after nearly two decades in prison.

But his journey back to freedom wasn’t easy.

A complex upbringing

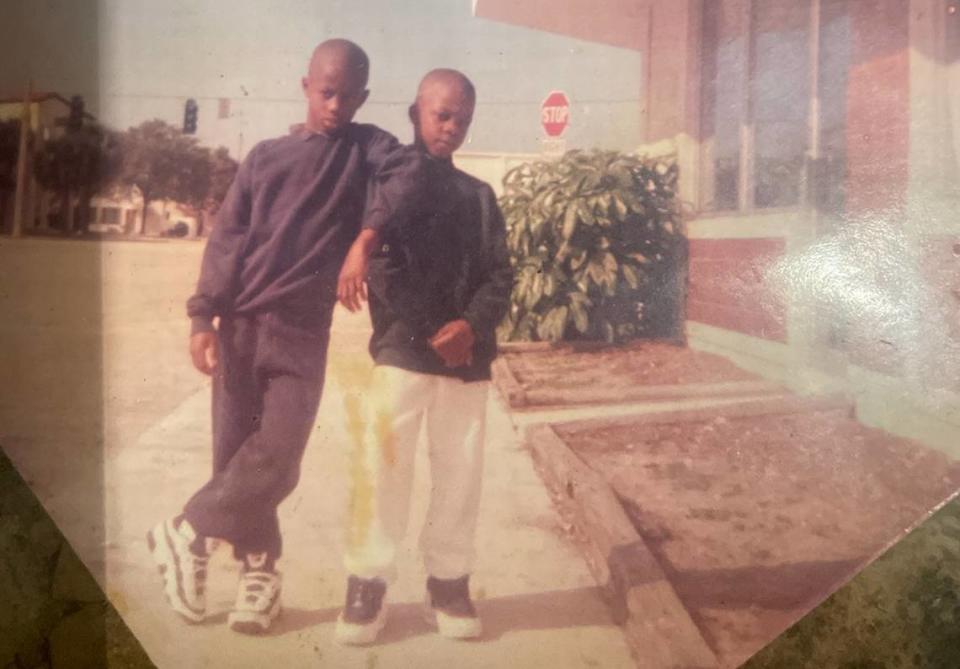

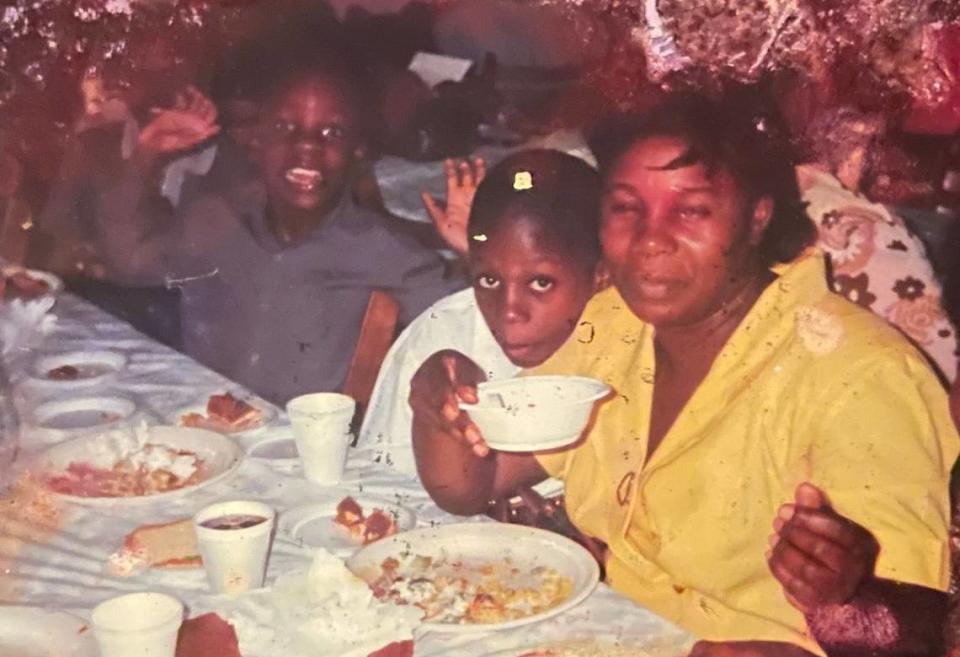

The place Jean called home was a slice of Haiti in South Florida. His family spoke Creole, and like many immigrants, held firm to their culture. He was a first-generation American with a curiosity beyond what he saw inside his Haitian household.

“I was a big ball of confusion within myself,” Jean said. “Every decision I was making was revolved around me being confused.”

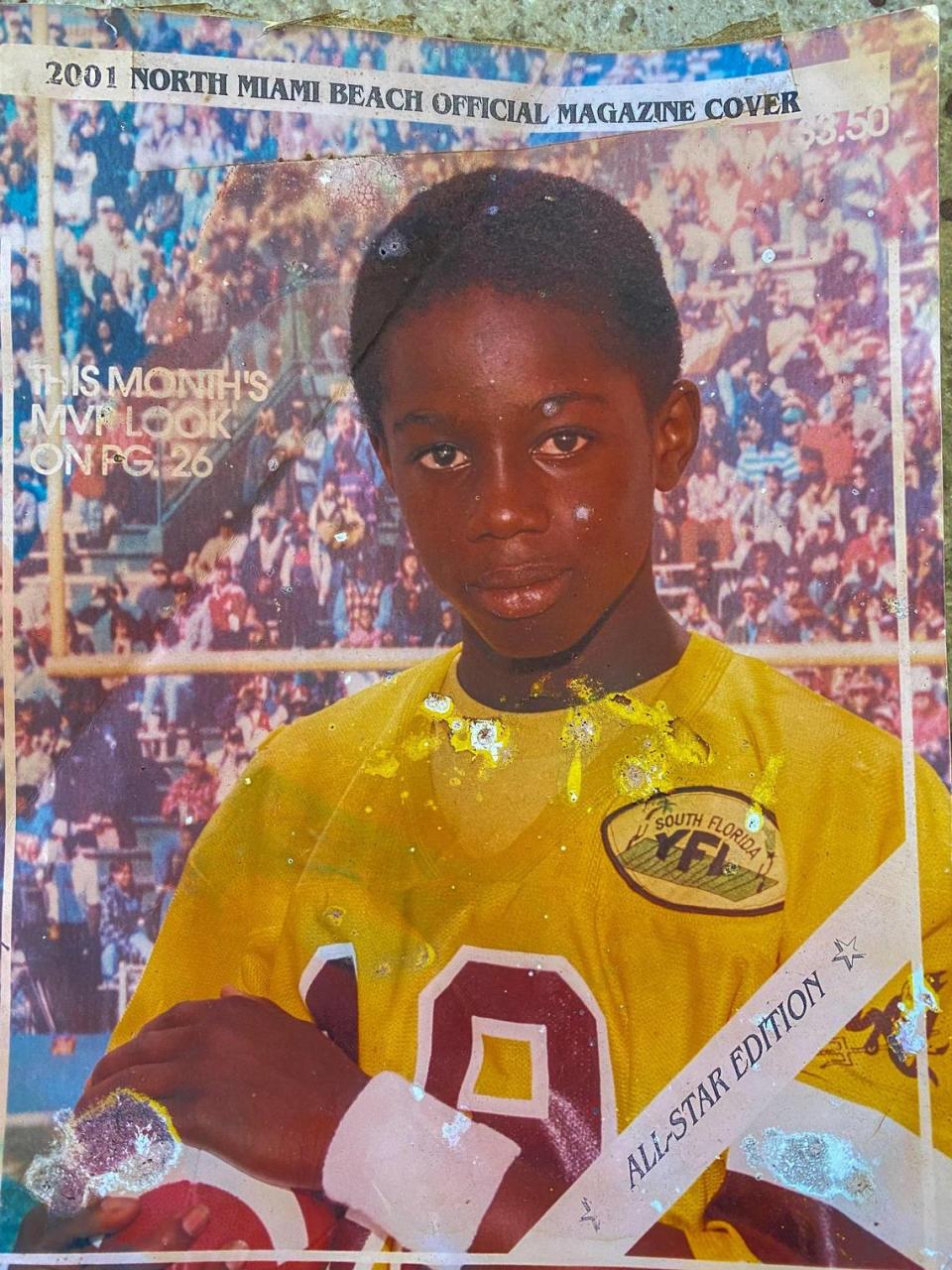

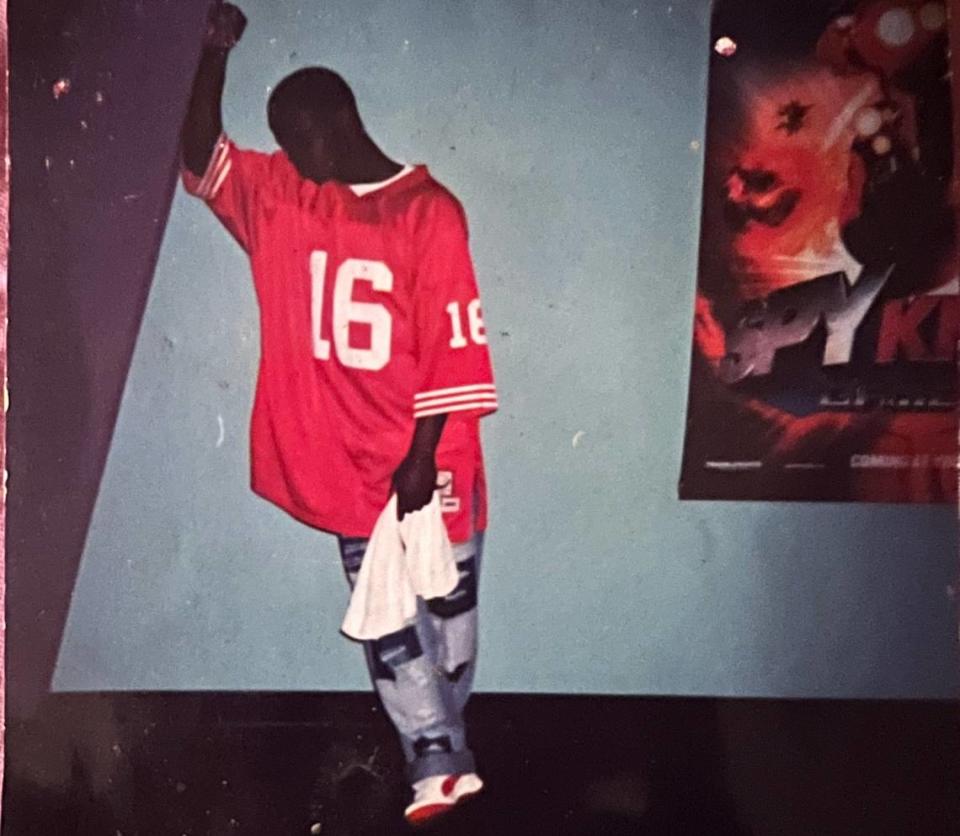

He quickly found his first love — football— at 6 years old, joining neighborhood kids for games in the evenings. The sport, however, introduced him to the streets. He sought ways to make quick money. His first attempt was selling comic books he drew.

As he delved deeper into the streets’ hustle culture, his trouble-making ways caught up to him. And in 1996, he caught his first charge: grand theft auto. He was paid $30, which sounded like $300 to 9-year-old Jean, to look out for police.

Jean chased the money to save up for the athlete-inspired sneakers that so many of his peers wore. Much like Michael Jordan, many of the era’s famous basketball players like Scottie Pippen and Penny Hardaway and even football players like Deion Sanders collaborated with shoe brands to design highly coveted kicks.

When Jean’s parents learned of his first arrest, they disciplined him, hoping to keep him under control. But the punishment didn’t do anything. Jean says it made him worse.

“Now, I’m sneaking outside every day,” he said about his childhood. “Getting a-- whoopings every day because I always had it in my mind that it can never be worse than the a-- whooping I got when I caught that felony.”

Jean’s home life also influenced his activity on the streets. His family didn’t believe in public housing or government handouts. They couldn’t put their pride aside, even though they struggled to get by.

One of the most traumatic moments in Jean’s life, he recalls, was witnessing his parents packing up their possessions and placing them in their car. They were just evicted from their North Miami Beach apartment.

Jean’s mother rubbed his father’s back as he sobbed. He had never seen his father, who he described as a “macho man,” cry. That pushed him to take matters into his own hands and sell drugs to help his family stay afloat.

For two weeks, the family shuffled in and out of motels until they could afford an efficiency in North Miami Beach, thanks to 15-year-old Jean’s help.

“I broke in that situation, but I could only play the cards that were dealt to me.”

In 2003, a judge sent Jean to the now-defunct Baypoint School, a former Department of Juvenile Justice initiative in southern Miami-Dade for middle and high school students. The 15-year-old excelled, raising his GPA and being allowed to play football at North Miami Beach Senior High, where he enrolled in 2004. He went back to Baypoint in 2005, learned calculus and had dreams of becoming an architect.

The streets, however, lured Jean back when he was released from Baypoint. He surrounded himself around “certain people” and put himself in “situations [he] might regret.”

That’s how Jean says he ended up caught in the middle of a murder case — just days before he was set to leave Florida for College of the Canyons in California. He was going to attend the junior college before suiting up and playing football for Western Michigan University.

The investigation — and Jean’s trial

At 19, Jean came to the attention of Detective Ed Hill, a North Miami Beach police officer — and a key character in Jean’s story.

Jean was a well-known face to many in the North Miami Beach Police Department. He says he was even beat up by several officers in 2001 while dodging a trespassing arrest. Fearing for his life, he recalls screaming out that he was 14, and they stopped.

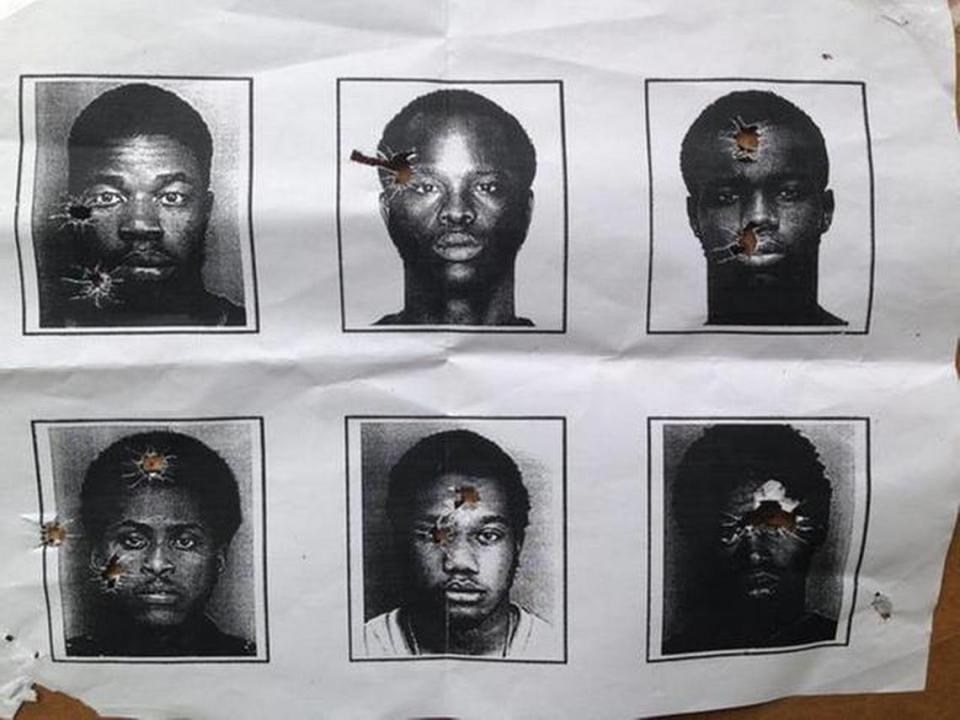

Jean’s mugshot was also on a photo lineup that the department used to help its sniper team practice marksmanship. The police chief suspended the training program in 2015 after outrage from the community over the revelation that cops were using real photos for target practice.

For Jean, considering his troubled history with the department, it wasn’t a shock that Detective Hill eyed him as a suspect.

“We’ve got to take the streets back,” Hill told the Miami Herald after the murder in 2006. “We’re not going to let these guys think they can do what they do to decent working guys, trying to make a living. We’re going to hit back hard.”

In the months that followed, police arrested Jean as well as Lazaro Esteban Cortes Jr., 19, and Richard Mikey Petit, 15, for the murder. Cortes didn’t have a record, and neither did Petit.

“These guys are a menace to society,” Hill told reporters after the arrests. “They’re a danger.”

While in jail, Jean was drawn to a Channel 7 News report that someone had been shot to death at a nightclub. He later found out that Vilner Simon, who he knew growing up, was the man gunned down outside Stingerz, a popular Caribbean nightclub in Miramar.

Simon’s family told reporters they believed the shooting stemmed from bad blood between Simon and Jean. Speculation mounted that Jean ordered the killing from his jail cell. Here we go again, he thought at the time.

“They made me look bigger than what I was.”

Despite relentless media coverage, the rumors slowly died down when another man was arrested in the shooting. But Jean always suspected that Simon had something to do with why he was behind bars.

“If it wasn’t for him, I would not be having this conversation.”

Cleared in Simon’s death, Jean headed to his murder trial in December 2010. The bulk of prosecutors’ evidence rested on witnesses identifying Jean, including co-defendant Petit.

Petit took a plea deal and said he was the getaway driver despite Cortes claiming that Jean was behind the wheel that day. Petit, who testified against Jean, only served seven years in prison.

Throughout the trial, Jean realized that the witnesses who identified him to detectives looked uncomfortable, like they were forced to be there.

“I knew there was some foul play,” he said. “Something had to happen for these witnesses ... to consistently pick me.”

When the jury’s verdict was read, Jean was stone-faced. The jurors found him guilty of murder, even though they determined that he never fired a weapon.

His eyes watered only as he heard his mother weep in the courtroom. He felt numb.

Botched police work?

From the moment he was found guilty, Jean kept busy in the prison’s law library. Though he transferred prisons about 10 times, he knew it would take a lot of effort to work on his case, almost like learning a new language.

He also knew he wasn’t destined for life behind bars.

“A word can’t explain the feeling.”

Jean balanced working on his case with reading self-help books and biographies of people he admired like Oprah Winfrey, Jeff Bezos and Jay-Z. He drew similarities in his life to the stories of LeBron James and Dwyane Wade, who all came up in what he calls “the trenches.”

“I started feeling human again.”

In 2011, he heard that Hill, the detective on his case, was under scrutiny after possible wrongdoing in another murder investigation.

Hill lost credibility for forging documents after he began romancing the wife of a suspect accused in a love triangle killing, according to Miami Herald archives. Miami-Dade prosecutors dropped the murder charge against the other man after handwriting experts concluded that key evidence provided by Hill was bogus.

Hill wasn’t charged but was forced to resign and give up his law enforcement certification.

His tactics came into question in the case against Cortes, Jean’s co-defendant. Defense attorney Sydney Smith asked a judge to throw out statements Cortes made because Hill allegedly coerced him into giving a false confession and implicating others. Smith speculated that Hill wasn’t criminally charged due to the dozens of investigations in which he was involved.

“If they prosecute him, he’s of no value to them as a witness,” Smith told the Miami Herald at the time.

Jean thought about filing an appeal based on the new evidence but decided against it because Hill wasn’t arrested. He had to find another way.

“It was gonna take hard work for me to prove my innocence,” Jean said. “But I knew this time was coming.”

Prayers answered

After filing several appeals, Jean still couldn’t shake the feeling that something was behind the witnesses’ odd demeanor. Desperate for answers, he contacted a new lawyer, who, in 2020, hired a private investigator to track down the witnesses a decade after the trial.

What the witnesses told the private investigator was Jean’s ticket to freedom.

Hill, according to court documents, convinced a witness to misidentify Jean as the shooter even though the witness specifically told Hill that Jean wasn’t the shooter. The detective then told the witness that the identification was the last thing police needed because all of the evidence pointed to Jean.

“The detective was embellishing one certain photograph and was leading me to pick that photograph,” the witness said in an affidavit, adding that he ”felt uncomfortable and pressured” by Hill.

The witness also said in the affidavit that he was “tortured by the fact that he had convicted an innocent man.”

“I found it difficult to live with myself after the trial,” the witness said in the affidavit. “I was apprehensive to come forward, knowing that I testified against an innocent man and the consequences.”

Up until then, Jean felt like Patrick Swayze in the movie “Ghost.” No one but Whoopie Goldberg — in this case, his loved ones — could hear him.

“I’m so used to being let down, and I didn’t even want to believe it,” Jean said about the witnesses’ statements. “I became so accustomed to losing, like it was natural for me.”

Co-defendant Cortes, who pleaded guilty and served 10 years in prison, made a sworn statement in which he said he linked up with Jean, meeting Petit for the first time that day, and hopped in the car with them.

Cortes had asked to buy a drink because he was thirsty after football practice, he said in the affidavit, and Jean went to buy him one at the store. When Jean returned, Petit said he, too, was thirsty and went into the store but didn’t return with a drink.

According to the affidavit, Cortes learned about the shooting later that night from Hill, who was his flag football coach. The detective called him and “urged him to identify Emmanuel as the shooter.”

“Neither Emmanuel or Richard ever told me that day that either had shot Mr. Ayoub, and I did not shoot him,” Cortes’ affidavit said. “At no time when either Richard or Emmanuel was in the car with me did I hear a shot.”

According to court records, Hill also hid a witness who knew Jean, saw the shooter leaving the store and told police Jean wasn’t the gunman.

“Unable to shake this witness, Detective Hill and his colleagues just erased her and her testimony from existence,” court records say.

The woman only learned that Jean was in prison in January 2021 after his brother Nahum posted about him on social media. She told Nahum that Hill questioned her back in 2006 and showed her Jean’s picture.

That was last time she heard from the detective.

Three major breakthroughs in his case. This is my time right here, Jean thought.

Redefining life

A free man for a little more than three months, Jean feels blessed, like nothing can stop him now.

He’s where he is because he let go of the grudges he held — and because of Coral Gables attorney Joe Klock.

Klock has known Jean since he was a teen, first meeting him when he made the honor roll at Baypoint. The lawyer was then the board chairman of the school. Since that day, Klock has been a source of strength in Jean’s life, someone he likens to idols like Usain Bolt and LeBron James.

Jean now works as a legal assistant for Klock’s law firm.

“You don’t find many people like him,” Jean said.

Nahum, Jean’s brother, agrees: “We’re blessed to have Joe in our life.”

Klock, like many in the community, never believed Jean was behind the murder. He was a bright young man — and now faces the challenge of rebuilding his life after years of being wrongfully incarcerated.

“This charge is just a result of corruption up in North Miami Beach,” Klock said. “The irony is that the police made a deal with the wrong guy.”

Jean credits God for the second chance. And he believes it was granted because of his personal growth.

“It was me I had to work on when I got put in this situation,” Jean said. “I was chosen. I feel like I was chosen.”

He’s now focused on his future and what he views as his new calling — trying to help troubled young people. He’s in the process of scheduling a visit to the juvenile detention center to speak with children and hopes that, in the long run, he can establish after-school programs that reach kids before they’re exposed to the justice system.

But Jean lost a lot in the process.

His father died in 2012. His mother, though constantly praying and staying strong for her son, suffered for more than a decade.

Jean’s mother vowed to sleep on the hard floors of her home until the day he would be freed. And Nahum said she stuck to her promise.

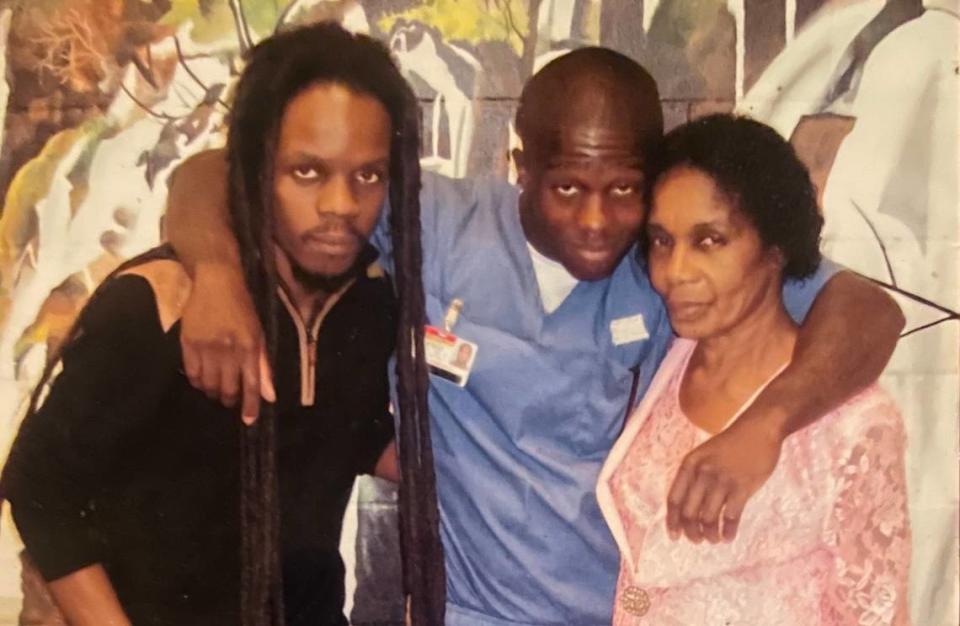

Now starting over, Jean reflects on the last time his mother visited him in 2016. He remembers that she wouldn’t stop yawning after making the more than eight hour-drive to visit Jean at the Northwest Florida Reception Center, a prison in the Panhandle.

There in the visitation room, he told her she didn’t have to come see him in prison anymore: “I’m gonna come see you, and this time it’s going to be forever.”

Though it took awhile, he kept his promise — just in time to celebrate his birthday with her for the first time in almost 17 years.