Founded as the first U.S. land-grant, can K-State reinvent itself for the 21st century?

MANHATTAN — It hasn't been two years since he arrived in the Sunflower State, and Richard Linton has already been in more than 80 of Kansas’ 105 counties.

The Kansas State University president has walked through the wheat fields of far western Kansas. He’s stepped through each of the state’s public universities and most of the community colleges.

And in meeting with ground-level community members and statewide leaders, Linton has come away with one impression.

K-State can do better — and be better — as it, the nation’s first land-grant university, redefines what it means to educate and serve the people of Kansas.

“It’s about re-envisioning and re-imagining what the general foundation is of a land-grant university, which is around research, teaching and outreach and engagement through cooperative extension,” Linton said. “All we’re doing is if we could have that foundation and create a land-grant university from scratch and knowing what’s important, what might that look like?”

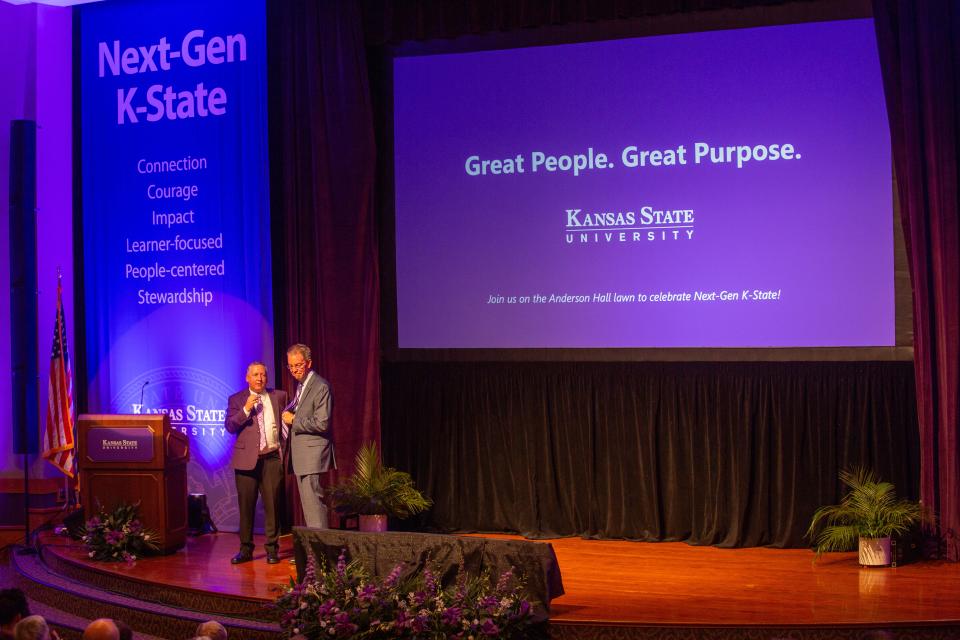

Kansas State University leaders on Friday formally unveiled Next-Gen K-State, the university’s ambitious plan to reinvent the concept of the land-grant mission and propel the university to be a national and world-leading institution by the year 2030.

Linton spoke with The Capital-Journal ahead of Friday’s State of the University address, which was given by chief of staff Marshall Stewart. Although he attended and spoke briefly at the address, the president is delegating some university leadership duties to Stewart while he undergoes treatment for tongue and throat cancer — news of which he shared with the K-State community over the summer.

But the plan, Linton points out, is much more than a single leader or even team.

To thrust K-State into the future, it will take university administration, faculty, staff, students, industry leaders and community stakeholders.

“It’s been a great year and a half, and to work at Kansas State, it’s just been an incredibly supportive network as we all try to work to make the institution better,” Linton said. ”Our goal is to be the best land-grant university we can for the state of Kansas, and we’re calling that Next-Gen K-State.”

After years of enrollment slide, K-State plan is 30,000 students by 2030

The university-wide vision and plan, as unveiled Friday, focuses on several measures to grow the university’s size, scope and vision as it seeks to fulfill its academic and research mission.

Linton, however, outlined three main areas of focus for K-State — teaching, research activity and community engagement through extension.

As far as student service, the past decade has been unkind to K-State in terms of enrollment. While many universities across the Midwest have seen slides in student counts as more high schoolers opt against pursuing higher education, K-State has been disproportionately affected, dropping gains over the past two decades and falling to enrollment levels not seen since the turn of the millennium.

The Next-Gen K-State plan, however, will hold university leaders accountable to reversing that trend by rethinking the university’s enrollment, which traditionally has been Kansas high school students seeking four-year undergraduate degrees across K-State’s Manhattan, Salina and Olathe campuses.

The plan calls for the university to reach 30,000 students by the year 2030 — split between 23,000 to 25,000 students pursuing traditional college degrees either in-person on campus or online, and 5,000 to 7,000 students looking for alternative credentials.

“On the teaching side, we typically think of students who physically come onto campus to get a four-year degree and graduate with that degree, when the actual true mission of a land-grant university is to provide education,” Linton said. “And it’s to provide education to all of Kansas.”

The K-State student of 2030 will be that undergraduate student, looking for a four-year degree.

But they will also be the student who transfers in from a partner community college, where they completed the first two years of a degree.

They will also be the nontraditional student who comes onto campus not even looking for a degree but simply needing a credit-bearing class that makes sense for their career.

“It might even be someone who is not looking for a degree at all,” Linton said. “Let’s say for example there’s someone who is 45 years old and working for Cargill who wants to elevate his career through data analytics. Well, data analytics didn’t exist 20 years ago, so how can we create certificates or microcredentials to help elevate someone in their career? How can we provide certificates and microcredentials that help someone who wants to get a job but doesn’t need a degree for that job?”

Competing for the same, dwindling pool of traditional undergraduate students in Kansas simply doesn't make sense, Linton said.

To an extent, it is a zero-sum game.

“We don’t have enough of a population in this state to fully fill all of the universities, whether they’re four-year degree providers, community colleges or private universities,” he said. “We just don’t have enough of a population. So if that’s the case, we need to think about how that number can be different, and we need to look at learners outside of the state.”

Over the past few years and amid ongoing efforts, K-State has created several programs to market itself at a more national level, drawing student interest from states around the country in a strategic way. Compared to land-grant universities in several other states, K-State can be the better option for many students, Linton said.

“Missouri, Texas, Colorado, Minnesota, Illinois, Nebraska, Oklahoma, California — these are all examples of states that are high target states for different reasons,” the president said. “Kids want to come from California to Kansas for very different reasons than the kids who come from Illinois.

“We’re actually cheaper out-of-state for high-achieving students than it is for in-state students at the land-grant in Illinois,” Linton continued. “Knowing that, and knowing there are so many students who don’t get accepted into those land-grants, it becomes an opportunity for us to offer those students opportunities.”

It’s lead to a 26% increase in out-of-state applications for the university, Linton said, and it’s a number he hopes to increase in the coming years.

And although fewer students from Kansas are pursuing higher education, K-State hopes to at least mitigate that number by focusing more keenly on affordability and student support.

The university in August announced an expansion to the entire state of its Land Grant Promise Act scholarship program, which guarantees free tuition for Pell-eligible students, once scholarships and other grants are considered.

Separately, but just as importantly, Linton said the university is focusing on improving its retention and graduation rates. Fewer than 50% of students graduate within four years of starting, and K-State’s goal is to bring that rate up to 55%, which is relatively high for most universities. The university will particularly target success for historically underrepresented students, including Hispanic students — who are one of the only growing demographics in the state.

When they do graduate, Linton said K-State will begin expecting every student to have some type of applied learning experience — be it an internship, practicum, apprenticeship, studies abroad or other type of real-world education.

Altogether, Linton expects the university’s efforts — combined with a $100 million push in new scholarships this past year — can make K-State more attractive for students, of all kinds.

“I don’t want you to be misled to think we’re going to go from 19,000 students to 26,000 of the same kind of students,” Linton said, although he does hope to see an approximate increase of 5,000 students at K-State’s Manhattan campus.

“What we need to do is we need to think differently, and instead of defining it as 'students,' we need to define them as ’learners,’” the president continued. “Within those learners, there are students and other kinds of individuals who need education in a different way.”

2030 plan calls for K-State to be a global leader in research

The second broad theme of Next-Gen K-State, Linton said, centers on the university’s research model, and how well the university’s academic output reflects the needs of the state.

“When we take a look at doing research at a land-grant university, it should be first for the good of the state of Kansas,” he said. “When we answer that question now on what is good for the state of Kansas, we have to ask, can we help the state? Can we create jobs? Can we bolster the economy?”

Much of Linton’s tenure so far has been traveling across the state and meeting with industry and state government leaders, who have pointed out that Kansas’ economy is trending towards growth in jobs in food and advanced manufacturing, biomanufacturing and animal health and diagnosics, among other fields.

To meet that need, K-State will have to dramatically boost its research expenditures, which it will do by focusing resources on research activity and soliciting and winning state and federal grants to support that work.

The goal is $300 million in research expenditures by 2030 — of which the university is making meaningful progress toward already. Compared to expenditures of about $180 million last year, K-State is already at $225 million this year.

“We’ve had a really strong research year, and in order for us to continue to expect that climb, it’s on us to be able to support the institution,” Linton said. “That means hiring more faculty, supporting the great faculty we already have and providing them with resources and programmatic incentives, enhancing and modernizing our research and laboratory spaces.”

Tied to enrollment as well, the university also hopes to focus on expanding its pool of graduate students who can help with tuition revenue but also boost the university’s research profile.

In terms of existing research, Linton said K-State is also rethinking how it approaches departments. Instead of singular professors or researchers siloed in separate academic units, K-State is focusing big on interdisciplinary studies, research and work.

That work, cumulatively, can establish K-State as an even bigger player at the national and worldwide levels, especially as that work pertains to agriculture.

“With (the National Bio and Agro-Defense Facility) coming here and with all that’s being done with the strengthening of our faculty relative to global food systems, Kansas State University ought to be known as one of the very top land-grant universities for global engagement, specifically around agriculture food systems and animal health and diagnostics,” Linton said.

“That’s in many cases our global bread and butter, and with the food animal corridor stretching from Kansas to Missouri, this is a space that we have to take great advantage of moving forward.”

Kansas communities want K-State to tackle health, housing and childcare issues

The third category of planning is engagement, which involves the university’s research and extension arm.

Traditionally, that branch of university service has “been about creating a sense of better well-being and opportunities both economically and in improving the quality of life in those communities,” including agribusiness, adult education and youth programs like 4-H.

“But really, what cooperative extension should be is to listen to what the state, counties and communities need right now,” Linton said. “And as we go across the state and we ask these questions to our external stakeholders, what they really need right now is in three areas: community health, child care and housing.”

K-State is framing its engagement strategy around what it is calling the "K-State Opportunity Agenda," which includes community health and well-being, sustainability, global food and biosecurity and enabling technologies.

Another issue that has come out as a pressing community need, particularly in western Kansas, is water.

“(Communities) expect Kansas State to lead a major water initiative that enables our state to be prepared for the water shortage challenges of today and tomorrow,” Linton said, referring to the university's efforts to develop a water institute to lead and solve water shortage solutions. “It’s taking a look at programs that help maximize the water we have in the state, and it’s going to vitally important for so many industries.”

Prioritizing those programs doesn’t mean leaving those traditional avenues of service behind, the president said. It will, however, mean more of a focus on creating those interdisciplinary teams to tackle pressing community and societal issues.

Engagement will also mean more than going out into communities, such as through the K-State 105 initiative to enhance the university’s presence in each county.

It will also mean inviting more industry and business leaders onto K-State’s campuses and hosting them alongside faculty to work together on solving economic and community issues.

“It’s listening to stakeholders across the state,” Linton said. “It’s listening to faculty about what they think is important. It’s about melting that together, and that’s your sweet spot in the work you need to do. Two things are going to be important in that spot: large, bold interdisciplinary teams and private-public partnerships.”

For too long, higher education institutions have been slow or reticent to adopt that model of working with industry, and the university has to make one message clear to the state, Linton said: K-State is open for business.

“With public-private partnerships, imagine the possibility of having a new building with these interdisciplinary teams and having industry in the building that gains value from working with these interdisciplinary teams, or working with students so that they can work every day on real, applied problems,” Linton said.

“That’s where change is made.”

How K-State will held itself accountable to 2030

The Next-Gen K-State strategic vision builds on and replaces K-State 2025, a similar plan started by former president Kirk Schulz in 2010 “to take the university to greater heights within the next 15 years.”

That plan, while foundational in the way it involved every single sector across the university, ran into various roadblocks, including stagnant state support and dwindling tuition dollars.

“Where we were challenged in that plan, is we had a financial catastrophe that happened right afterward, and it was difficult to provide the resources that would enable us to get there,” Linton said. "And because we didn’t have the resources, we didn’t have a watchdog team that could always be watching and thinking on how we were doing in meeting the metrics — how much progress we made.”

Next-Gen K-State will have an appointed team of university leaders to hold the university accountable to its goals, Linton said.

Additionally, K-State will compare its progress to peer universities with similar profiles as K-State is today — such as Auburn University, Iowa State, Oklahoma State, the University of Arkansas and the University of Nebraska — and aspirational institutions that reflect how K-State wishes to see itself.

Those include Colorado State, Louisiana State, North Carolina State, Oregon State, Purdue and Georgia universities.

Right now, K-State is marketing itself around the state as “the University for Kansans,” a tagline that perhaps sounds much like the name of its peer institution down the Kansas River.

Any suggestion aside, Linton says that push is part of a larger effort to “reclaim” Kansas and let the state know that it is first and foremost, a land-grant university by the state and for the state. Later on, that marketing effort will reflect that K-State is also a university for the nation, and ultimately, for the world.

As Linton reflected on his travels around the state so far, he said he’s found an incredible passion by Kansans for K-State — asking what the university can do for them, and what they can do for the university.

At the top of that list is building a talent pipeline, stimulating the economy and creating jobs.

“People are very happy to see a president going around the state,” the president said. “We weren’t as present as we could have been, and certainly COVID was a big part of that. But I noticed that the resilience in people around the state to support the land-grant is very strong, and it doesn’t take much."

"It takes being present, and listening," he added, "and doing what people would you to do to make the difference."

Rafael Garcia is an education reporter for the Topeka Capital-Journal. He can be reached at rgarcia@cjonline.com or by phone at 785-289-5325. Follow him on Twitter at @byRafaelGarcia.

This article originally appeared on Topeka Capital-Journal: Next-Gen K-State 2030 promises student enrollment, research growth