Founder of Decode Project aims to be part of literacy solution in Louisville's West End

A locker stuffed with homework papers that hadn’t been turned in wasn’t an act of defiance. It was the manifestation of LaToya Whitlock’s struggle to learn.

Whitlock's teacher at Carter Traditional Elementary School in the West End, Norma Jean Jefferson, saw the challenges of her pupil and decided to take action. She put together a separate system for Whitlock, who had been diagnosed with ADHD in fourth grade, that was agreed upon with Whitlock’s mother, who’d grown frustrated with her daughter not doing her homework.

“If I was given several tasks, I would struggle with that. I'd do the first thing or the last thing,” Whitlock recalled. “And so (Jefferson) said, ‘I'll give her a task. Send her to her seat. We'll highlight it. If she completes it, then she can go help someone else. And then she can come up to my desk. And I'll give her the next task.’”

Soon, Whitlock’s locker became a little less cluttered. The strain that once existed between her and her mother and grandmother about her lack of homework completion subsided. They’d gotten over the educational hurdle.

“I loved school, but the way that school was set up, especially in spaces where I was placed, it just didn't work for me,” Whitlock said. “It took special educators who decided they could see the potential in me to pour into me.”

BETWEEN THE LINES:Why Kentucky's kids can't read and who's to blame

Many years and a sociology degree from the University of Louisville later, Whitlock now stands as the Norma Jean Jefferson figure to those in her community as the co-founder and executive director of Decode Project. The organization is a literacy program designed “to eliminate inequities in education by fostering a diverse community of learners prepared to navigate the world,” according to its website.

“It was just a different person (at different times) who saw me and said not you, not now. I'm going to help course correct for you,” Whitlock added about people like Jefferson who impacted her as a child. "I think that that allowed me to believe that if there's an issue, there's a kid who has an issue in particular, or a family that has an issue in particular, that if you're not a part of the solution, then you're part of the problem. And, I always want to be a part of the solution.”

Seeing the problem

At 19 years old, Whitlock learned that being a journalist wasn’t for her.

While working at WHAS, she was pained by the lack of position news and felt a duty to consider the impact each story had on the Louisville audience, her hometown community.

Finally, she’d had enough. Reporting on issues was no longer sufficient for her.

Whitlock wanted to fix them.

A career pivot to social services eventually brought her to Louisville's West End School, which now occupies the same building where she first attended elementary school. She was working as a counselor and one day noticed a first-grade boy on the brink of getting kicked out of school. Months after the first grader had been written up for throwing a chair in class, Whitlock had an enlightening conversation with him.

“I asked him, ‘Does that even sound like you? Are you that guy?’” Whitlock recalled. "He was like, ‘No, I'm not that guy. I probably did all that because I didn't know how to do anything else.’ The fact that he could articulate ‘I did not have the tools, but now that I do, my behavior will change.’ And, it did.”

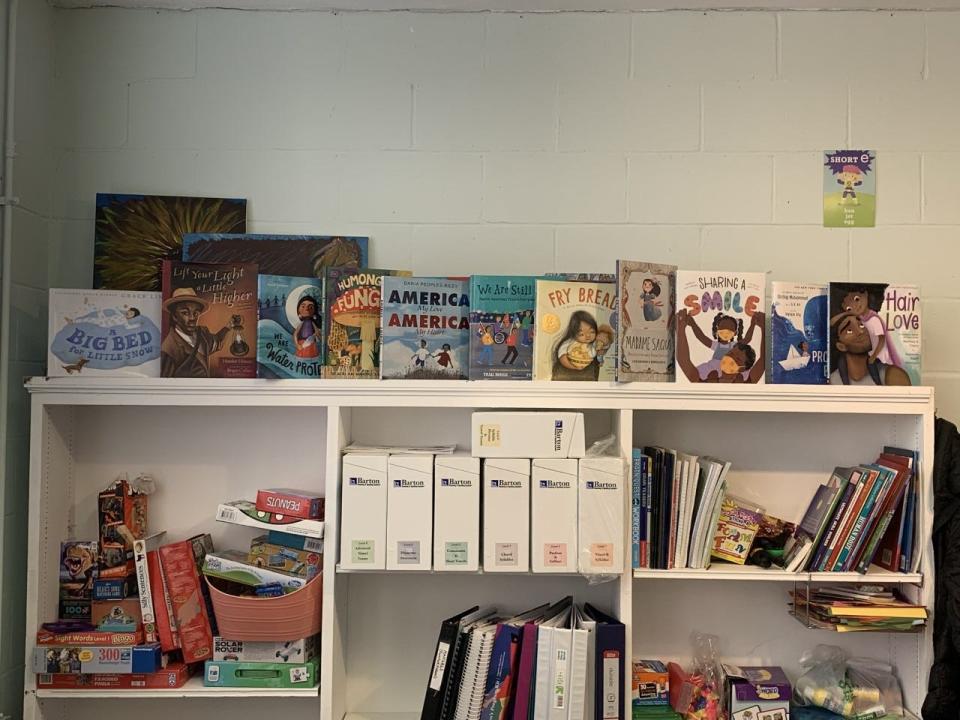

The tools were a gift from a school volunteer in the form of an educational program called “The Science of Reading” that was becoming more popular nationwide. Whitlock was hesitant to try it, but the ultimatum of doing the program or expulsion for the young boy was enough motivation for her to do it.

A week later, the results were in.

“(The teacher) tells me that he's willing to sit in his seat or spelling test, he's able to get five out of 10,” Whitlock said. “While that doesn't seem like it's something to celebrate, for him, it really was. It's all relative.”

A learning disadvantage:1 in 5 children may have dyslexia. Kentucky doesn’t seem to care

Much like with Whitlock’s mother when she was growing up, the breakthrough in learning mended the rift between the first grader and his parents, she said. Celebration of small, significant victories replaced frustration of misbehavior. The program had worked. Soon, it would be used on a broader scale at the school and tweaked to fit the specific needs of the students at West End School.

“I'm a big believer in Greenspan's different theories of how individuals learn,” Whitlock said. "I embrace that, and I think that it has worked for the kids.”

The more Whitlock shared the program with others, the more she discovered that learning deficiencies weren’t just limited to West End. They were a problem across the country.

Once again, Whitlock jumped into action. She launched Decode Project in mid-October 2018.

Creating a solution

LaToya Whitlock sat around her dining room table with Christa Rounsvall and Chenoweth Allen, two of Whitlock’s colleagues. Together, they created a blueprint for Decode Project. It didn’t gain much traction with the local schools until the COVID-19 pandemic hit in 2020. They started working with students at the local Non-Traditional Instruction (NTI) hub and expanded from there.

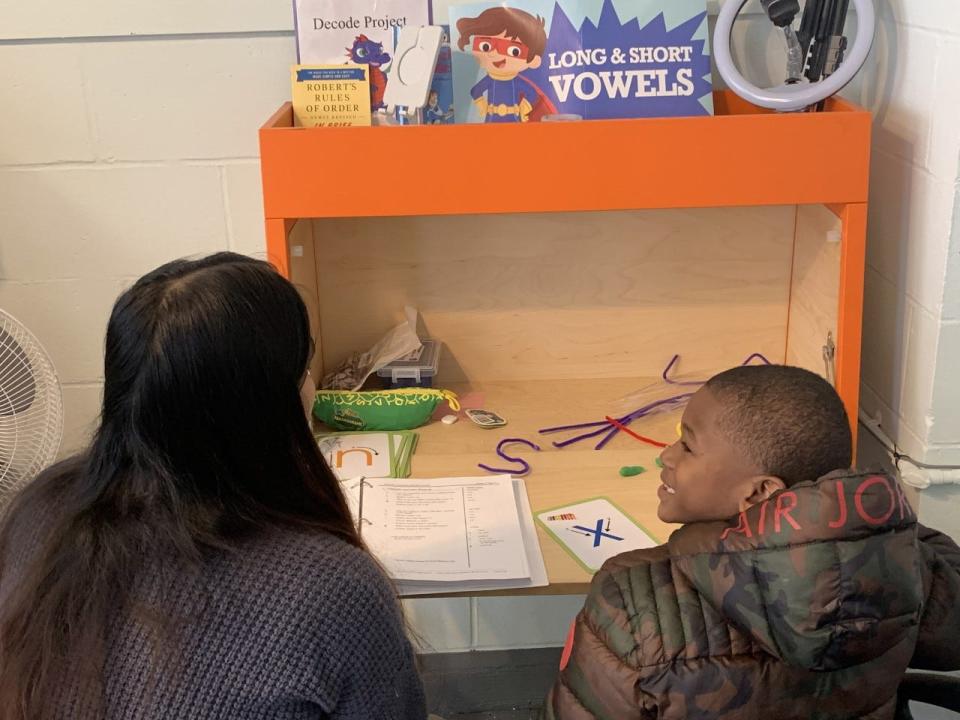

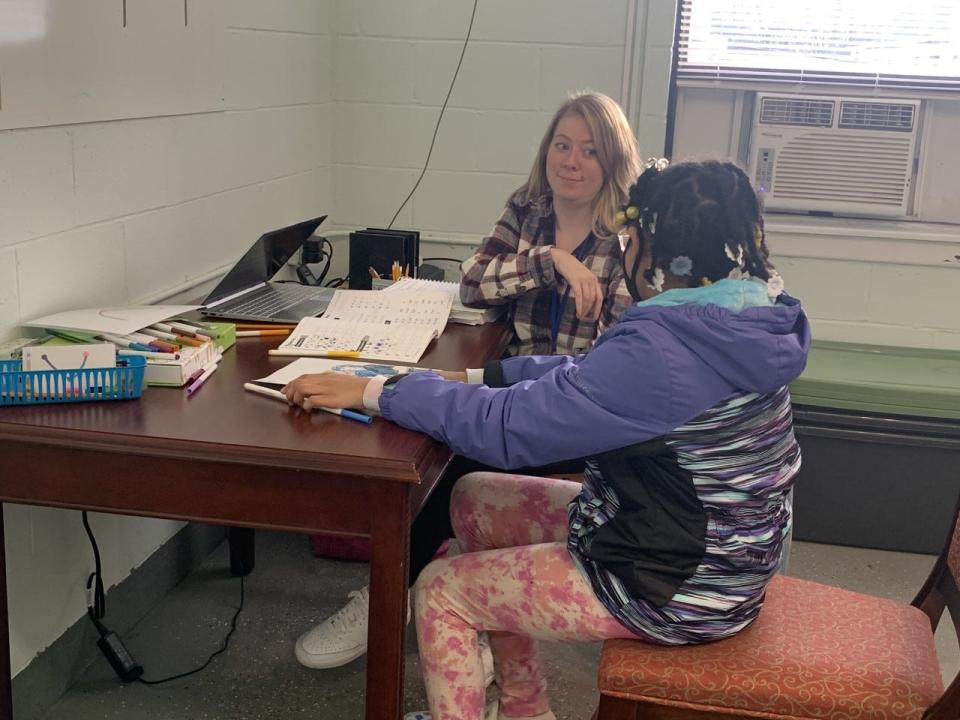

A dining room idea with three volunteers has expanded into a fully operating non-profit organization over the last four years. Decode Project employs four full-time staff members “and counting,” Whitlock said, along with 19 literacy mentors. It serves around 400 students and has partnered with organizations like Global Game Changers, Play Cousins Collective, Byck Elementary School and Martin Luther King, Jr. Elementary School, among others.

Funding comes from grants and donors, who Whitlock prefers to refer to as “champions.”

When asked what makes Decode Project different than what she’d seen before, former schoolteacher and current literacy programs manager Janelle Henderson said, “Explicit instruction.”

“Having a phonics foundation and using what we know works best for kids,” the Louisville native added. “Storytelling, using their entire bodies, not just making sure they know and can memorize what we're doing, but there's something they can retain with it.”

More than just sowing into the lives of children, Whitlock has also impacted those who work around her.

“I tell her (Whitlock) all the time that I want to be her when I grow up,” said Abby Vansickle, a literacy mentor at Decode Project who is pursuing a master's degree in social work at U of L. “She's done a lot of things that kind of parallel the goals and dreams that I have from school counseling to starting her own organization and doing the things that she sees is important.”

Added literacy programs manager Jerusha Beebe, “She won't let people talk about her in the way that she's like a super person, and I get that, but at the same time she is. It's hard work with her and not feel inspired because she shows up. She pushes you in a way to really connect with why you do what you do. I really appreciated the opportunity to be able to work with her and to learn from her.”

Whitlock recently participated in The Courier Journal’s Between the Lines forum, created following the CJ’s five-part series on lagging literacy rates among young students in Kentucky. It would be easy to leave Louisville for another area – or even state – to apply these same practices, but Whitlock chose to invest in the community that invested in her.

Whether it was Jefferson, one of her childhood church members or a community leader from the dance company where she attended, Whitlock is a product of the village around her. Now, it’s her turn to do the same for another student (and their locker).

“Many of the caregivers that we work with, when we explain to them the signs and symptoms of what their child might be experiencing, are in tears and say I struggle with the very same thing when I was in school. I wish we had a decode project,” Whitlock said, fighting back tears. “That gives us purpose. This is not in vain. This isn't just, I had an idea one day. It's necessary.”

Reach Alexis Cubit at acubit@courier-journal.com.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: Decode Project founder LaToya Whitlock uses personal past to help kids