François Clemmons Reflects On Making History With Mister Rogers

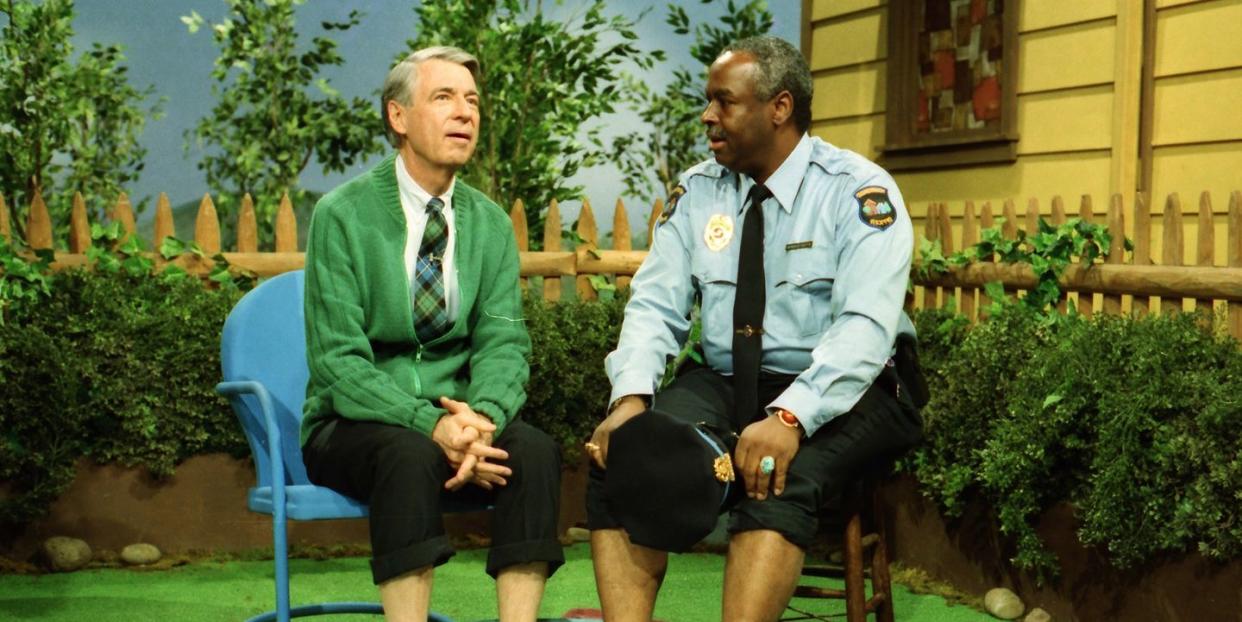

On an episode of Mister Rogers' Neighborhood in 1969, Mr. Rogers famously asked François Clemmons, one of the first recurring Black characters on a kids' TV series, to soak his feet in a foot bath with him on a hot day during. It was an invitation for Clemmons—but also for all Americans to stand in solidarity with the Black community.

Through 1993, Clemmons was featured in 98 episodes of the iconic children's show. He came to Mister Rogers' Neighborhood in 1968, amid a civil-rights movement that eventually led to a symbolic show of Black allyship from its beloved series's namesake, Fred Rogers. Racial tensions were high. Recreational segregation was widely enforced.

Clemmons retired in 2013 after 15 years as Middlebury College’s artist-in-residence and director of its Martin Luther King Spiritual Choir. Now 75 years old, he says he is still asked about Mr. Rogers whenever the world is in crisis.

"People are always saying, 'What would Mr. Rogers do?'" Clemmons tells OprahMag.com, reflecting on the image now, as the country again is confronted with a racial reckoning that has galvanized Black Lives Matter protests and marches around the world. "You should be saying, 'What should we be doing?' You and me. This is our time. Fred had his time."

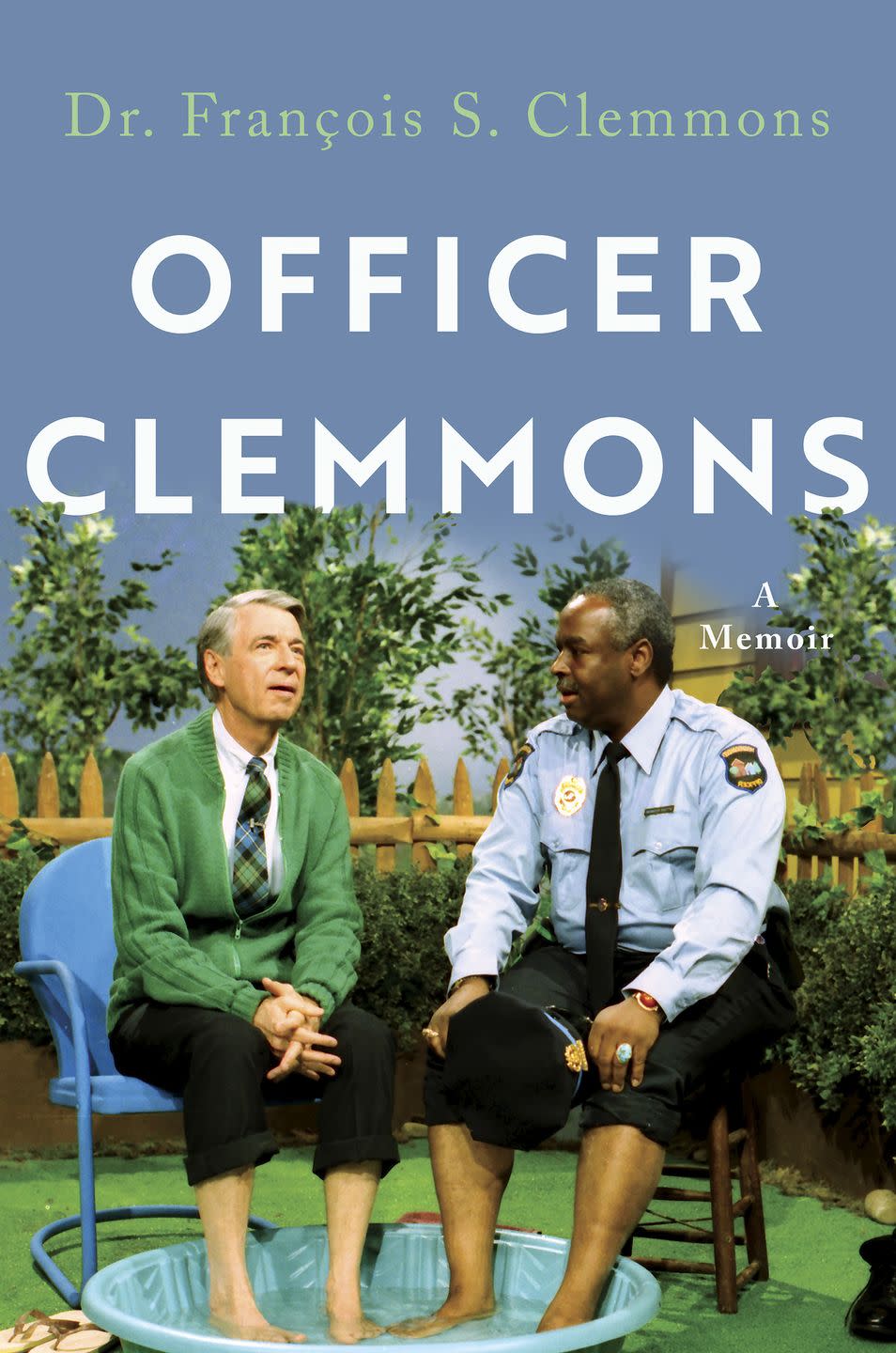

In May, when ex-cop Derek Chauvin pressed his knee on George Floyd's neck for a stomach-turning eight minutes and 46 seconds, the vintage snapshot of Clemmons and Rogers began to make the rounds again. It flooded social-media feeds as a statement of what America could be and inspired many reflections on the photo's enduring relevance. Floyd was murdered just weeks after Clemmons's memoir was published, on May 5.

With that same iconic pool scene as its cover photo, Clemmons's book personalizes the experiences of racism and homosexuality during the 1960s civil-rights movement, chronicling his own harrowing youth as a Black, then-closeted gay man growing up in Birmingham, Alabama. There, he was raised in a violent home environment, with a neglectful mother, an abusive father, and a stepfather who didn't accept him being gay. He found his joy in singing, and went on to become a trained Grammy-winning opera singer.

It was his voice that ultimately captivated Rogers. After hearing Clemmons croon some of his favorite spirituals at a Presbyterian church in Pittsburgh on Good Friday in 1968, Rogers was so moved he asked Clemmons to be the officer on Mister Rogers' Neighborhood. The two would forge a lifelong friendship; in 2018, during our first conversation, Clemmons referred to Rogers as his "surrogate father."

But he was still shocked by Rogers's offer. He wondered: Why would a white man ask a Black man to play the kind of man Black people fear? He ended up turning down the role—until Rogers convinced him otherwise.

"Franc, people are going to look up to you for singing that way, and going around the neighborhood, being a part of the community," Clemmons recalls Rogers telling him. "That is going to change a lot of people's opinions about policemen. I swear to you, Franc."

Clemmons's initial hesitancy was the result of dreading even a passing encounter with the police as a young boy in Birmingham, where he observed far more white cops than Black cops. Growing up, aunts and uncles—but also, "everybody"—taught him how to behave in the presence of a policeman: "Don't look straight at them. If they come, lower your eyes. Keep walking. Don't walk fast. And don't say anything."

As a kid, Clemmons remembers witnessing a horrific act of police violence against a young girl; her dress over her head, the officer held the girl down, his body weight sinking into her with immense force. Decades later, Floyd's murder led Clemmons to meditation—sitting, praying—even though he was also "filled with rage."

As the Black Lives Matter movement marches on, Clemmons is reminded of his heroes: Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and Rogers, who died in 2003. He also admires the movement's Black women leaders, including BLM co-founders Patrisse Khan-Cullors and Alicia Garza, who are spearheading today's fight for racial justice in a similar manner to that of Rogers because "they call on a moral law, and they practice that." He says the message Rogers was sending in 1969 is much like the one being sent currently: "You cannot treat your neighbor like that."

In Officer Clemmons, he recounts an encounter with a racist conductor who demanded he get off "my stage" while his Neighborhood co-stars prepared for a show at the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra. Emotionally distraught, Clemmons explained the situation to Rogers, who provided the kind of protective safety and comfort Clemmons could count on.

In his book, Clemmons recalls Rogers confronting the conductor, speaking "calmly but with intent." He writes that Rogers said, "In our neighborhood, we don't talk like that, and especially to one of our neighbors.” An apology was demanded. If one could not be given, he told the conductor there would be no show.

As he reflects on Rogers's loyal allyship to him during that incident in the 1970s, Clemmons stresses that, now, the same kind of committed support needs to be given to vulnerable Black transgender communities from white gay America—as the latter demographic, he says, "have achieved a certain kind of social acceptability."

"You have an obligation to your Black sister and your Black brother, and your trans sister and your trans brother," he says. "You can't just walk away. If white people are silent, we cannot win this battle."

Even though this is our battle to fight, if Rogers was to tell you what to do, "he'd tell you get out and help, in any way that you can," Clemmons says. "You do not have to go out on the front lines and get a gun and use it in order to be helpful. But you do have to help people change the minds of those who are dedicated to hurting Black people."

How does Clemmons suggest you be a good neighbor? "Call your local congressman."

Part of his own contribution, Clemmons says, is his memoir. He hopes his resilient life story will serve as a model of perseverance for those being condemned for who they are like he once was, particularly in the Black queer community. When he was a boy, he had no one to tell him this—and so, with his book, "I wanted to be able to say to them, 'Your life is valid.'"

Now that his story has been told in his own words after decades of working toward its publication, Clemmons still has more to accomplish. One achievement, he says, was realized with this very story—to see his name appear under the O, The Oprah Magazine title—has long been a dream. And he's up late every night writing another book. For it, he says, "I meditate and have almost an out-of-body experience, and I go away with him," referring to his enduring spiritual bond with Rogers. (His first book was Songs For Today, a volume of American Negro Spirituals, published in 1996.)

He writes at his Vermont home, where he's been in pandemic isolation for the last six months with his Tibetan terrier Princess. There, he greets friends from his porch at a safe distance, and reads the fan mail that is still sent to him in steady streams. He humbly writes back to his admirers, many of whom are real-life Black cops who felt they could effect change like Clemmons did as a groundbreaking fictional one. With a graciousness that still moves and surprises Clemmons decades after dipping his brown feet in a bath with Rogers's white feet, they write to him with a shared sentiment: gratitude.

"I'm amazed that something I did 50 years ago still resonates in the breadth of the nation," he says, warmly. "I mean, people know what I did. And they talk about it. Everywhere I go, they talk about it."

For more stories like this, sign up for our newsletter.

You Might Also Like