Francis Bacon, from Tormented to Mellow, in Houston

The Houston Museum of Fine Arts’ new blockbuster is Francis Bacon: Late Paintings, which opened at the end of February. Organized by the MFA and the Pompidou Center in Paris, it looks at Bacon, an icon and an enigma, from the early 1970s to his death in 1992. Bacon was a nervy, sulfuric, irascible artist. Did his core traits intensify as he aged, dissolving features that once smoothed the rough edges? That’s what happens to most old people. Or did this angry, turbulent atheist mellow?

The exhibition is a grand one, and it looks perfect in the MFA’s Mies van der Rohe galleries. Not a bucket but a pint of curatorial detachment dampens Bacon’s fire, though. The show doesn’t run away from anything but broaches where I’d attack and knead and pound. Was it the interpretation or the art itself that left me cooler under the collar than I expected?

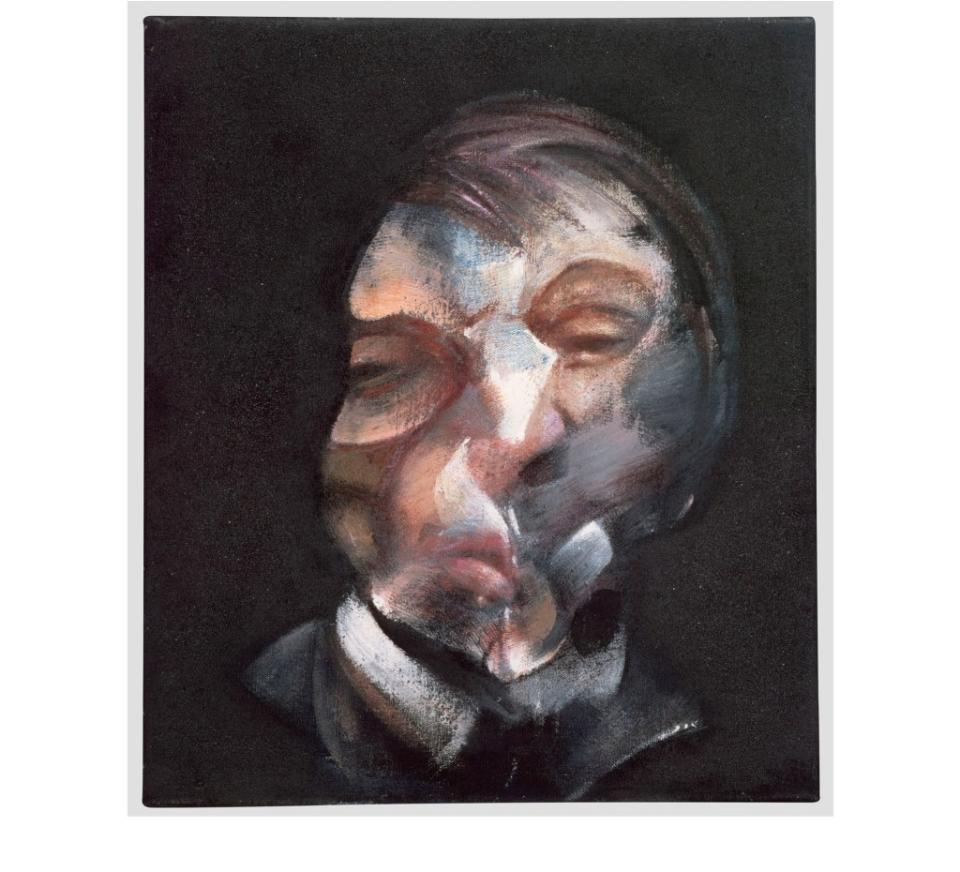

Born in Dublin in 1909, Bacon had a career that spanned 60 years. His crucifixions, deformed self-portraits, triptychs of gnarled figures, and demented popes are instantly recognizable as Bacon’s, but familiarity doesn’t mean I can ever look at them and shrug. His figures are studies in contrasts. He deforms the human figure, twisting torsos and amputating limbs, but his figures spin like dancers or tops. Convulsion is controlled. His palette isn’t neon, garish, or scary, however often he paints blood. He uses lilacs, grays, soft yellows, and browns. He takes us to this weird point where the lyrical and the brutal are in equipoise. It’s a strange beauty.

Bacon was untrained and self-educated and a gutter prodigy, making him a folk artist on steroids. He’s a brand, too, as instantly recognizable as Pollock, Warhol, Picasso, and a few others. And he was a brand who made good copy. He was a celebrity. A brawling Irishman, once a call-boy, always a drunk and a hot gay mess when homosexuality was scandalous, Bacon was a poster boy for complexity and his era’s favorite dark genius. He was also immersed in Aeschylus, Shakespeare, Nietzsche, T. S. Eliot, and Joseph Conrad, to drop a few names.

I’m skeptical of brands, which can become shtick, or a high-dollar routine. Artists sometimes problematize as a marketing tool. Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst, and the Wyeths come to mind as the schlockiest of self-promoters. I’m not necessarily hanging their baggage on Bacon, though he was a cunning, coy interview subject. The show left me asking question after question. First, it’s called “Francis Bacon: Late Paintings” while the catalogue is called “Francis Bacon: Books and Painting,” which puzzles me. Why? Literature and art demand very different things from us, and the writers that the catalogue links with Bacon are themselves big, complex beasts

I loved the show, but I’m unsure whether or not my take on Bacon is anything like the curator’s.

The exhibition, and Bacon’s late period, begins with a death. In October 1971, Bacon reached a career zenith. A retrospective of his paintings was about to open at the Grand Palais in Paris. He’d been famous for years, mostly known as a surrealist whose dream figures were grotesque and repellent. The night before the triumphant opening, Bacon’s longtime lover, George Dyer, killed himself in their Paris hotel room. The exhibition notes this directly and calmly, says that Dyer’s death triggered the things that preoccupied Bacon as a painter until his own death, and moves as calmly and directly to a group of Bacon self-portraits.

We quickly surmise that Bacon was a narcissist, since he did 23 self-portraits in the next three years. It’s very clear he was a selfish bastard, too, hardly a victim but a brutish victimizer. Meanwhile, inside me is my outdoor voice screaming, “Who’s George Dyer?” We learn next to nothing about him, how they met, what their relationship was like, or why, hours before Bacon’s show opened, Dyer took his own life. There’s not a photo of Dyer in the show. Dyer was quite a character, I learned in reading the catalogue.

In other words, I would have been happy to dwell in the gutter that was Bacon’s life circa 1971. Bacon’s Triptych in Memory of George Dyer, from 1971, is in the first gallery. I’m okay with saying that being gay, Irish, and Catholic in the last century was a tried-and-true path to a tortured life, and Bacon made nihilism and pain his calling cards. If Dyer’s death was the dynamite that exposed Bacon’s end-of-career painting, we need to know more about Dyer and, for that matter, the other men in Bacon’s life. What’s Bacon’s history? He’s a visceral, angry artist, supposedly, so there’s a disconnect between the art of angst, of tragedy, and the scholarly reticence and detachment that rules the show’s mood. I’ve always looked at Bacon as the last gasp of Romanticism. He’s the stuff of opera but in the exhibition, Bacon and his dark, disturbed moons become specimens.

As I walked through the show, I was struck most by Bacon’s sheer technical brilliance. When I write about shows, I dive deeply, but there’s always the wake of the last show I’ve tackled. A couple of days before I saw the Bacon exhibition, I wrote a long story on Goya’s drawings. Goya was a technical genius, and with a twist of a brush dipped in wash, he’d create an entire figure. Bacon had the same mastery of medium, and I know he admired Goya. Bacon worshipped Velázquez, too, who could create depth and dazzle in a dab of oil paint.

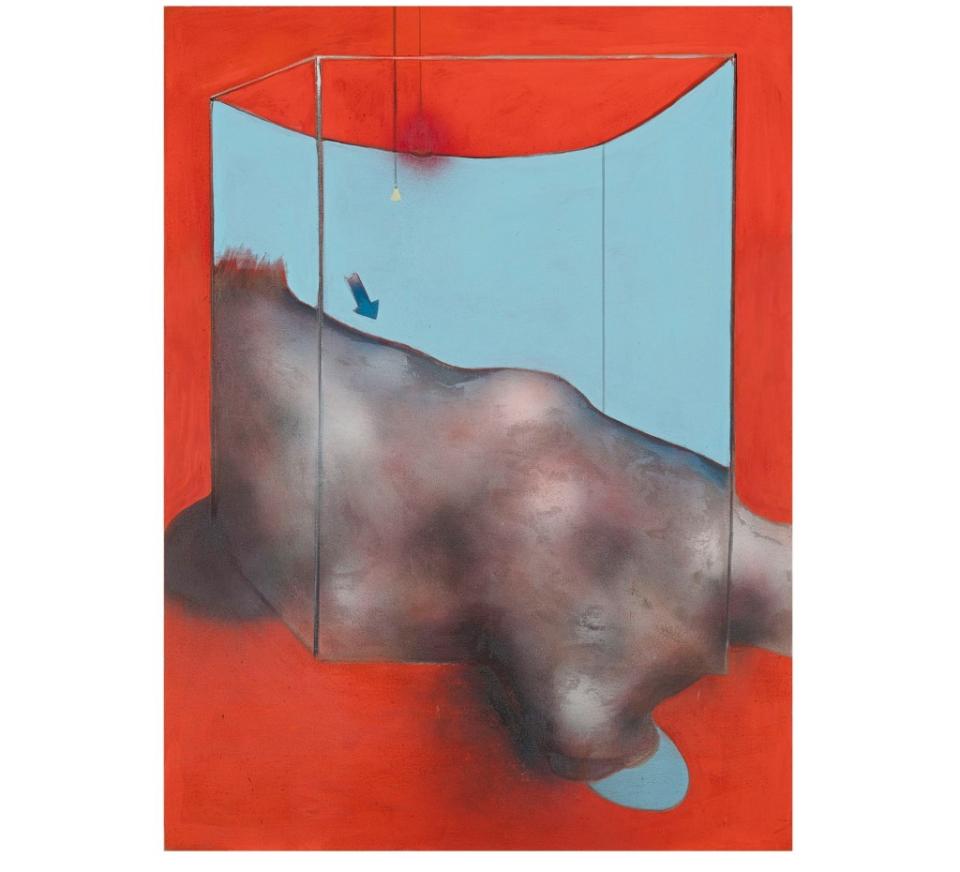

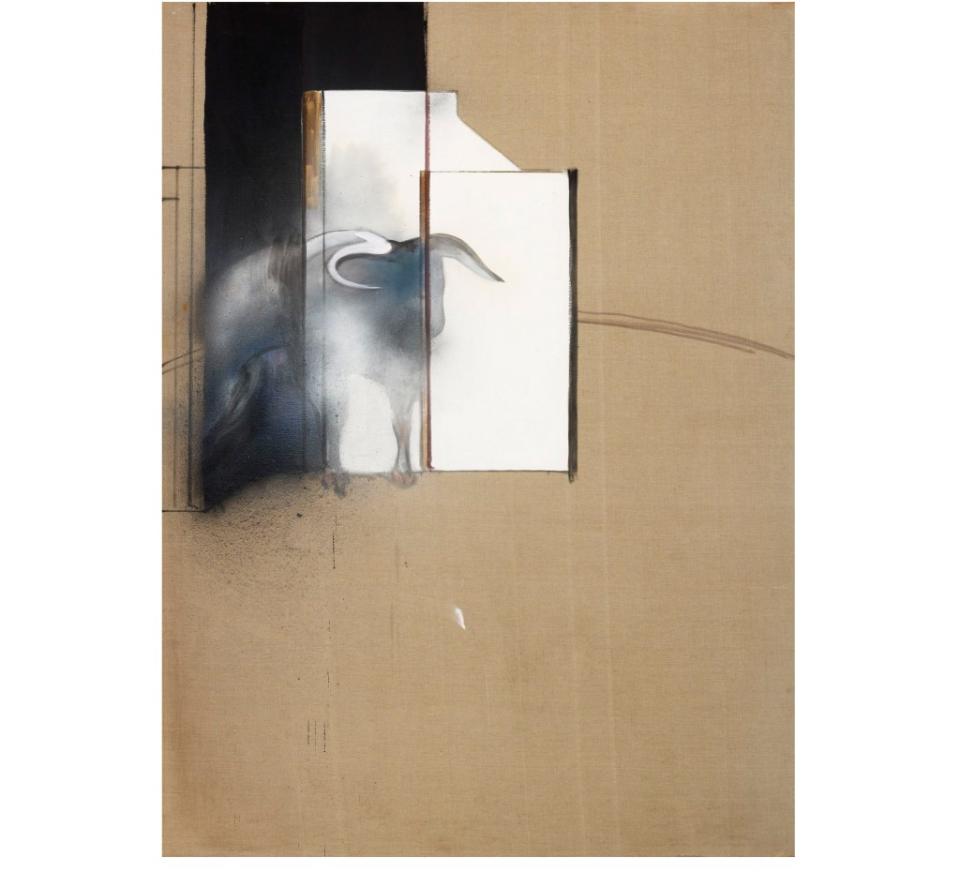

Bacon is that good a painter. He’s after a crepuscular world where the creepy creatures of the night are just coming out. He uses oil paint to give figures structure and body and then pastel to make them elusive and subtly dematerialized. In Sand Dune, from 1983, he adds a material called “dust.” “What’s that,” I said to myself. It’s gathered dust bunnies, entirely believable as I’ve seen his studio, reinstalled at the Hugh Lane Gallery in London, and it’s a sty. With dust to spare, he makes a textured surface. He also uses spray paint for his backgrounds. Bacon’s pictures are big, routinely 78 by 58 inches. Spray paint makes for a flat, textureless backdrop for figures painted in oil, giving the figures more sculptural relief.

Triptych, from 1986 to 1987, is the most frustrating of his late triptychs. On the left, he interprets a photograph, well known in the 1910s, of President Woodrow Wilson leaving the Quai d’Orsay after signing the Treaty of Versailles in 1919. On the right, he depicts the lectern that Leon Trotsky used moments before he was hacked to death with an axe. The central panel shows a male nude in cricket pads. The man resembles John Edwards, to whom Bacon left his estate when he died. I’m all for mystery, but this is the most bizarre history painting I’ve ever seen. In an interview in the mid-1980s, Bacon was asked about the meaning of his more cryptic pictures. “I mean people can interpret things as they want,” he said. “What I do, I may like the look of, but I don’t try to interpret it.”

Jet of Water, from 1988, is Bacon’s one, belated homage to abstract expressionism à la Pollock. He threw a can of paint on the canvas, hoping to create a form that looked like a wave. Bacon thought it looked more like a jet of water so, in finishing the painting, he aimed at that. Michael Peppiatt, the leading Bacon scholar at the time, interpreted it as an allegory of humanity’s destruction, “swept from the stage.”

Bacon was pleased enough with the picture to brag about it to the extent that he said he liked it. It resolves itself, more or less, into the deck of a ship, and Bacon had just painted Woodrow Wilson and Trotsky, two of the biggest and saddest figures to come from the First World War. Is this a sinking ship? The Lusitania, after all, sank off the coast of Ireland in 1915. Is Jet of Water an addendum to the triptych that Bacon did the year before? That’s overreaching, I think, and the pitfalls of Bacon studies. Its opacity is the clearest thing about it. I think it’s a simple experiment with paint and juxtaposition of forms. A handsome picture, yes, but apocalyptic it ain’t.

Puzzles like this can drive a viewer crazy, as does dangling Aeschylus, Shakespeare, and Nietzsche. What we don’t see in the late work are screaming faces, crazy-looking popes, and mutilated animals. We see sand dunes, water, here and there a body part, or Trotsky’s blood splatters. We see bullfighting scenes, but bullfighting is as much about preening, strutting matadors in high glitter as it is about killing bulls. We see nude men wearing cricket pads. Bacon might have said in 1962 that “man now realizes that he is an accident, that he is a completely futile being,” and so much of his work focused on pointless cruelty. His late work left me thinking of Rothko’s, when Rothko limited his palette to grays and blacks, when Rothko’s work had a soothing, spiritual feeling.

I suppose I left the show thinking this: Bacon evolved from a painter of violence, pathology, and extreme upset-ment, his twisted soul splattered in oil, pastel, dust, and aerosol on canvas — to become a deft, cool stylist. He mellowed. I’m a big fan of technical brilliance, beauty, and aesthetic refinement, so this is fine. Piling on doom and gloom — Greek tragedy, Macbeth, King Lear, jungles, and wastelands — can smother the joy of looking at Bacon the master sensualist. That’s more a problem with the book than the exhibition. The show, in its light interpretive touch, allowed me to leave thinking that lyricism seems to have won the day. I was not shocked to learn that Bacon, an arch atheist, died in a Roman Catholic hospital in Spain, treated by nuns, a crucifix over his bed. Whether he liked it or not, it seemed a poetic ending.

I hadn’t been to the MFA in 20 years. It was a treat. I wrote about its trenchantly good Italian-design show last week. It’s also showing the Bacon exhibition, the Norman Rockwell Four Freedoms show, and the Hispanic Society’s treasures show. This season, the museum is indeed offering Houston an eclectic feast. The place is broadly appealing. It was hopping and buzzing while I was there. At the same time, it’s academic. Like the best big museums, it feels like a university.

The MFA is indeed a campus, set in 14 acres in the Museum District in Houston, not far from Rice University. I think it’s one of the great civic museums in the country, the more-or-less encyclopedic big-city museums. A civic museum caters to a city or region holistically, with a catholic exhibition program and engagement with the local schools. There’s something for everyone. Almost all civic museums are private, but locals take pride in them. A good civic museum tells the world its home is cultured. The MFA conveys all of this with panache. Its buildings are handsome with blue-chip pedigree — Mies van der Rohe and Rafael Moneo designed the two anchor spaces.

Texas came late to the museum business. New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Chicago established civic museums in the Gilded Age, but the booms in population and money came to the Sun Belt later, in Texas starting in the 1920s. When I started as a curator, the MFA was a nice, regional museum with good Old Masters and American art. Its highlights reflected the idiosyncrasies of local collectors. Ima Hogg, for instance, collected early American art. Rich as Croesus, she went whole-hog-and-add-the-brisket for this field, starting in 1920s when the Colonial Revival was underway. It’s an elegant collection, displayed in period rooms at Bayou Bend, a separate building that looks like Tara and was constructed specifically for American decorative arts.

The MFA has lovely impressionist and post-impressionist things, too, gifts from Audrey Jones Beck. Beck’s father, Jesse Jones, made a fortune in “bidness” of all kinds. He was Will Rogers’s best friend and an FDR crony. Daughter Beck bought art she thought the museum needed to have. In the 1970s, the museum decided to focus money on photography, a smart choice since photographs were cheap then. Today, its 40,000-object photography collection is one of the world’s best.

Propelling the MFA to the big league was a 2005 bequest totaling over $400 million from Carolyn Weiss Law, whose father made his money in, as the song went, “oil, that is, black gold, Texas tea.” I believe it’s still the biggest bequest in the history of American museums, and almost all went into the endowment.

In writing this piece, it occurred to me that I’ve known all the MFA’s directors over the past 50 years, starting with the then young Philippe de Montebello, who directed the museum before he went to the Met. Peter Marzio was the once-in-a-lifetime director. He led the place for 28 years until his unexpected death in 2010. Peter had vision and ambition. He also had humility and humor. Texans will roll the dice, cautiously since they aren’t fools, and Peter persuaded rich Houstonians to make the museum the city’s cultural magnet. He was a bottom-line director and a diplomat, too, and that’s rare. He was rarer, still, as a fundraiser. He was the master of the touch so soft it’s invisible. Rich people came to him, checkbook in hand, asking him how much he needed.

Marzio also did something every corporate consultant tells directors not to do. He had 125 direct reports — almost everyone in the museum reported to him — but no one called him a micromanager. He hired good people and let them do their jobs. I’ve known so many egotistical, narcissistic blowhard directors. Peter was the antithesis and even the antidote. When he spoke at museum-director meetings, the preeners and carnival barkers among us kept quiet. Gary Tinterow is the director now. He was the curator of French painting at the Met for years, though he’s a Houstonian by birth. He’s suave and smart. He understood when he got there that the museum was heavy on European art. Its American art was treated as European colonial art, or as one chapter in the history of Western art. Texas is a border state, and Houston’s museum is reaching south for contemporary art. That makes sense.

Museums, for better or worse, are always in some phase of a construction project, and the MFA is no different. It’s nearing the completion of a 237,000-square-foot-building for 20th- and 21st-century art designed by Steven Holl Architects. Holl’s landmark museum building, the addition to the Nelson-Atkins in Kansas City, is beautiful, with the same vertical translucent glass tubes that will clad the Houston building’s façade. The new building will complement the MFA’s current spaces, designed by Mies in 1958 and Moneo in 2000. The cost of the project is $450 million, and it’s been raised. That’s Texas can-do spirit!