Frank Gehry in battle to transform LA's famous concrete riverbed

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Its featureless concrete banks have for years framed some of Hollywood's most memorable blockbusters.

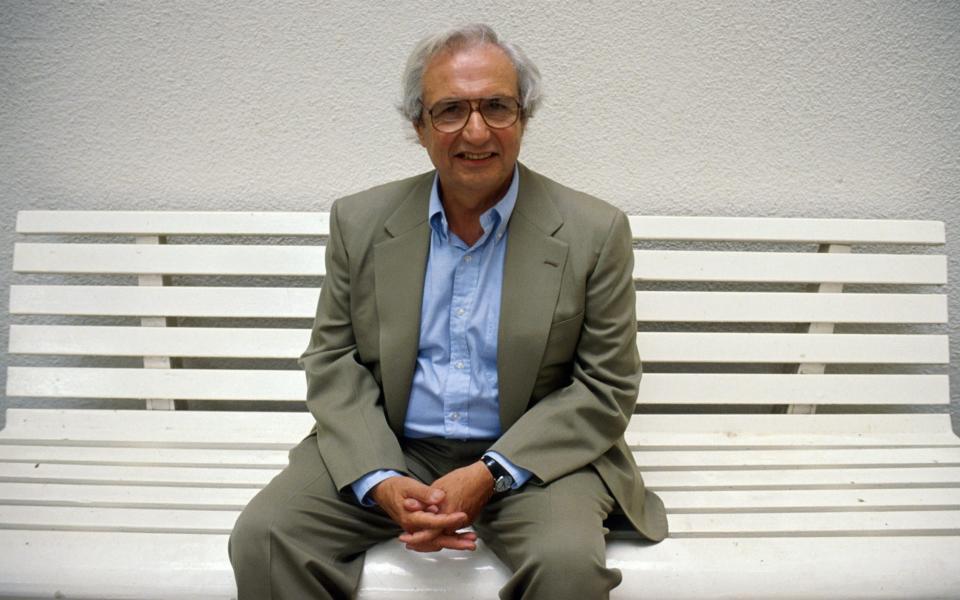

But sections of the artificial river bed on which John Travolta raced Greased Lightnin' and Arnold Schwarzenegger drove his Harley Davidson as Terminator could soon be hidden by a canopy of parks and greenery in a project led by superstar architect Frank Gehry.

Mr Gehry, the man behind Bilbao's Guggenheim, wants to transform the channel that cuts through the heart of some of LA's poorest neighbourhoods in a plan that it is hoped will help regenerate blighted riverside communities.

Designs released this week illustrating the latest stage of his vision show parks on stilts connecting districts cut off from one another, adding to previous proposals for a $150 million cultural centre and a river flanked by trees and trails.

But the changes face stiff opposition from environmentalists battling to restore the eyesore to its former glory as a natural river. Meanwhile critics are warning that the designs are leading to real estate speculation that could spell gentrification rather than poverty eradication.

Since it was built following a disastrous 1938 flood the LA River channel has been blamed for dividing communities, creating and reinforced racial and ethnic enclaves along the river.

Its waters still run 51 miles from the San Fernando Valley down to the sea, but they are boxed in and tainted with industrial and agricultural runoff, that continues downstream through Chinatown, Bronzeville and Sonoratown.

The artificial river not only divided but it also displaced in what many say was a textbook example of LA using urban design as tools of racial segregation.

Post-war freeways were carefully routed around white areas and straight through diverse ones. Loss of industry and jobs subsequently drove out white residents and wiping out tax revenues.

Meanwhile iling cities slashed regulations and invited in big polluters such as the Exide battery recycling plant, forced to shut down in 2015 after filling heavily Latino districts with airborne lead.

“Revitalizing the river offers ... communities an opportunity to rebuild our connections, to the river and each other,” said Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon (D-Lakewood), whose 63rd Assembly District includes South Gate, Bell and Long Beach. “Southeast LA deserves parks and trails, education and cultural centers,” he added. “Equity comes when every community has access to the tools to make life better.”

Mr Gehry is one part of a fragile coalition of activists, urban designers and local officials with grand plans to turn the channel into a unified green corridor running through the city. Beyond that, agreement breaks down.

The architect's vision - backed by Hollywood executives and real estate developers - has not impressed environmentalists who have worked for decades to restore the river to its natural state before the 20th century, when it was busy with wildlife and regarded as sacred by the indigenous Tongva people.

"A lot of people don't actually know that LA has a river," says Geoff Manaugh, an LA-based journalist who documents hidden and overlooked urban spaces. "When they hear 'the LA River', it almost sounds like an oxymoron or some sort of practical joke. It's central and yet peripheral in people's consciousness, because they don't really see it... it's like the unconscious of the city."

In 2010, the river received federal environmental protections, and today one can kayak along its marshier sections, watching birdwatchers watch birds and photographers snap newlyweds. Environmentalists see this as a model for the whole river. In November a group of nonprofits called for them to be ruled out as an option, saying they "stand to do particular ecological harm, create real estate speculation, and precludes future opportunities for climate resilience."

Mr Gehry, now 91, shot back at the environmentalists' model this month, saying that “beautiful romantic greenery would displace people".

The buzz of renewal is already heating up the housing market all along the water, inexorably threatening to displace low-income tenants. "There's going to be a lot of new property along the river primed for new ownership, and we highly doubt that it's going to be the current residents who can afford it," says Jessica Prieto from East Yards Communities for Environmental Justice, a campaign group. The LA County master plan tries to mitigate this with more affordable housing and a county land bank. But Ms Prieto says it won't be enough without holistic tenant protections and housing market reform: "You can't build your way out of a crisis."

Mr Manaugh sees the river battle as a conflict between LA's past and its future – between its 20th century obsession with paving over nature and its growing desire to rediscover the "landscape beneath the concrete". The latter approach, he believes, could bring a new outdoor economy to Los Angeles. So while he does not oppose the platform parks that have already been mooted, he would not want to see them become a blueprint for whole of river. "That," he says, "would be a mistake equal to the Army Corps of Engineers' original mistake."