A New Frank Lloyd Wright Biography Explains the Architect’s Complicated Relationship With His Father

Frank Lloyd Wright’s famously prodigious career saw the design of over 1,000 buildings, the construction of more than half of those, and now, 60 years after Wright’s death, a striking commitment to preserving his works. Earlier this year, for example, UNESCO designated eight of his buildings, including Fallingwater and Taliesin West, as World Heritage Sites, bolstering the prospects for their ongoing preservation. Even in consideration of this impressive oeuvre, one of Wright’s most enduring designs could turn out to be, well, Frank Lloyd Wright. His public image of a singular genius, which he did so much to cultivate, has persisted well into the posthumous years. To create the character of Frank Lloyd Wright, the figure pictured in magazines and on television, he used his everyday accoutrements—the porkpie hat, cape, cane, cravat—but to create the myth of a once-in-a-century genius, he constructed his own life story in ways that would reinforce that very idea.

Wright’s autobiography is, in the words of Paul Hendrickson, “one of the great memoirs of the 20th century, even if you must distrust it on every page.” Using that sense of skepticism as his point of departure, Hendrickson, a former newspaper reporter, spent seven years investigating the life of Wright, culminating in the newly published book Plagued by Fire: The Dreams and Furies of Frank Lloyd Wright (Knopf, 2019). Not a biography with a cradle-to-grave purview, Plagued by Fire is, instead, a collection of episodes, each drawn from Wright’s life, each which points to what Hendrickson considers to be evidence of Wright’s humanity. The 1914 tragedy that saw a domestic worker at Taliesin slaughter Wright’s longtime companion and fellow household staffers with an ax while setting a blaze that burned down the architect’s beloved studio, gets sustained and focused attention, but Hendrickson also turns his consideration to those human stories less dramatic than a mass murder and conflagration but no less impactful on the human experience: Wright’s spurned relationship with his father, for example, or his experience of growing old. In ways not dissimilar from another recent architect biography, Walter Gropius: The Man Who Built the Bauhaus (Harvard University Press, 2019), Plagued by Fire aims not to examine the work of an architect but rather to render the architect with human character.

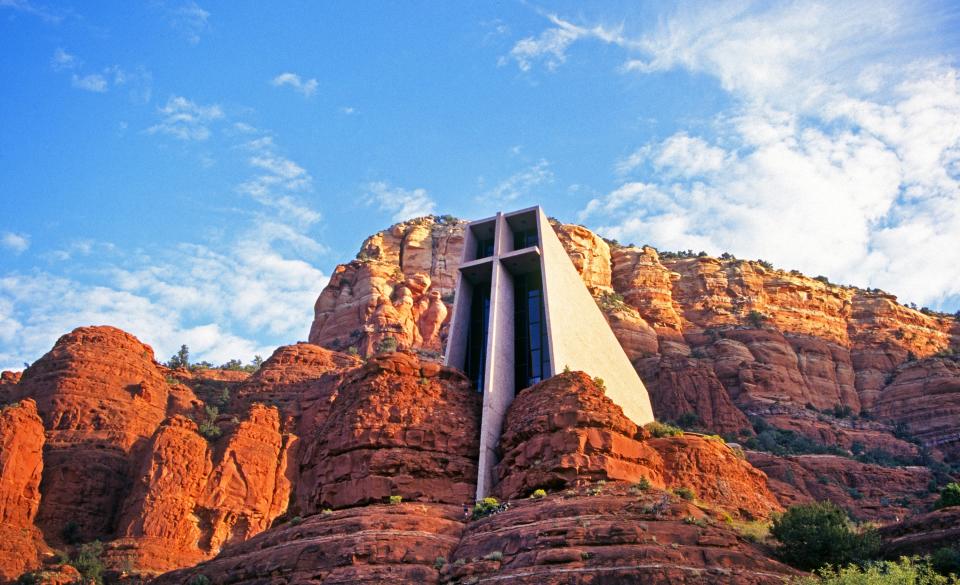

Chapel of the Holy Cross Church, Sedona, Arizona Landscape

The Frank Lloyd Wright bookshelf is a crowded one. Hendrickson concedes as much in the prologue, saying about Wright biographies, “Depending on how you count, there are about eight or nine of those, and never mind how many hundreds of historical studies, monographs, coffee-table treatments, scholarly examinations.” Plagued by Fire offers fresh material and newfound evidence. “I’m an old shoe-leather journalist,” says Hendrickson, referring to his instinct to turn up hard-to-find evidence. “My method was to get my fingers in the documents. All of that was trying to go where some of the silences are.”

Exterior of Taliesin West, the winter home and studio of architect Frank Lloyd Wright.

He was able to color in those silences using extensive research, looking both into documents and archives pertaining to Wright himself, but also into the historical record of what would have been Wright’s context. After learning of the 1914 massacre at Taliesin, for example, Wright left Chicago by train to visit the scene of the tragedy. Hendrickson doesn’t leave it there. Instead, he researches the route he traveled to better understand that moment of Wright’s life. “To study old CM&SP [Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway] timetables is to get an appreciation for the crawling agony of that evening,” as he says in the book, one of many such examples of cross-references to the facts of Wright’s experiences.

Throughout the book, Hendrickson’s focus is on the all-too-often overlooked evidence of Wright’s own vulnerabilities, so the book’s most moving passages come from fresh insights from the architect’s archives. Hendrickson cites the Sunday morning talks Wright would deliver to his Taliesin Fellowship as an example. “I found his Fellowship talks at Columbia’s Avery Library, and these by and large have not been examined by scholars. He’s giving these talks extemporaneously, and he’s saying things so powerful about his father.” This discovery is one of many in the book, which, as Hendrickson puts it, starts to reveal Wright’s humanity. “It’s too easy to box him up as a supreme artist and insufferable egotist,” he says. “When you look closer, you start seeing the complicated real man.”

Originally Appeared on Architectural Digest