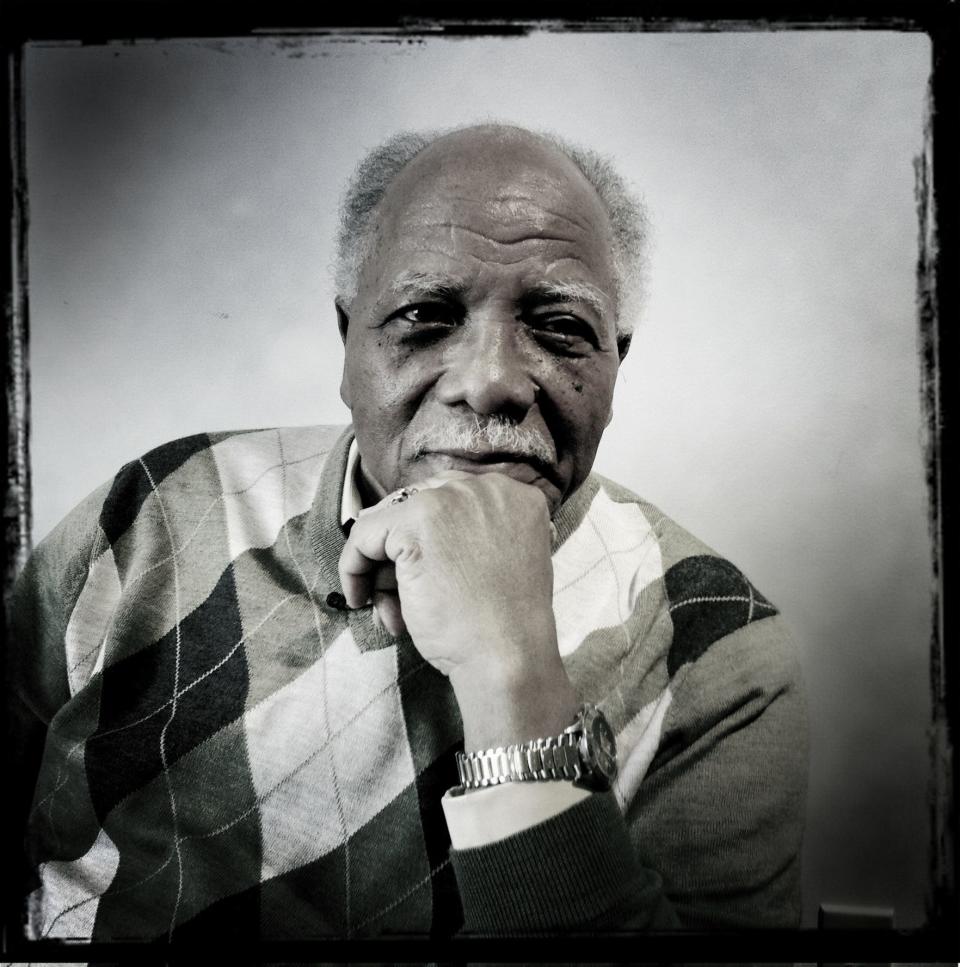

Franklin Florence, civil rights leader, dies at 89

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This story has been corrected to reflect Florence's accurate age. While his birth year was widely reported throughout his life as 1934, his family -- and his voter registration information -- say it was in fact 1933, meaning he was 89 years old at the time of his death.

The Rev. Franklin Florence, the founding president of FIGHT and the face of black power in Rochester in the 1960s who stared down Kodak at the height of its power to obtain jobs for black Rochesterians, died Wednesday at age 89, according to his family.

No specific cause of death was given, but he had been ill for some time.

Minister Florence, as he was widely known, was one of the most recognizable and controversial people in Rochester in the years after the 1964 riots. More than any other black leader in the city’s history, he changed the call for civil rights from a request to a demand.

“He was, and is, the most charismatic man that I've ever met,” Raymond Scott, a later FIGHT president and Florence disciple, told the historian Laura Warren Hill in 2008. “He was a fiery, godly man with a passion for justice.”

“I don't know too many who walked with him that did not revere him. … But, for him, you were either with him or against him. And man, if you were against him, you had a fight on your hands.”

Boy preacher

Franklin Delano Roosevelt Florence was born Aug. 9, 1933, in the black Overtown neighborhood of Miami. His mother was a domestic worker; his father, a railroad worker and ice salesman, died when he was 3 years old, and his mother remarried a longshoreman who had been converted to the evangelical Church of Christ.

The family read the Bible together every evening, and the Rev. Florence became a “boy preacher” under the aegis of the influential Southern evangelical Marshall Keeble. He attended the Church of Christ-affiliated Pepperdine College in Los Angeles but dropped out after two years.

The Rev. Florence spent five years preaching in Florida before taking a job in 1959, at age 25, as pastor at the Reynolds Street Church of Christ in Rochester. He was paid $65 a week with lodging upstairs from the sanctuary for him, his wife, Mary, and his children.

He first gained local prominence as an advocate during a series of police brutality cases involving the Rochester Police Department. The most notorious involved 28-year-old Rufus Fairwell, who suffered two fractured vertebrae in a scuffle with police. They thought he was breaking into a Plymouth Avenue gas station when he was in fact an employee there, locking it up for the evening.

The Rev. Florence developed a friendship with Malcolm X, who visited Rochester several times in the years before his assassination in 1965.

“That man, he left us so proud of being black,” the Rev. Florence recalled in a lengthy 1985 interview published in Upstate Magazine. “Malcolm spoke for the man who was saying, ‘No more gradualism for the system. Everything wrong about it had to come to an end.’”

He was visiting his family in Miami in July 1964 when the Rochester uprising took place but quickly returned to the city and stood at the forefront of the newly urgent demand for racial justice. The following summer he was elected president of FIGHT, the militant new black organization that was to dominate the local civil rights agenda in the crucial years to come.

The name was an acronym: Freedom, Integration, God, Honor, Today. The Rev. Florence drew inspiration from St. Paul’s exhortation in his first letter to Timothy: “Fight the good fight of faith.”

“For those who trust the people, it is a dawn of a new generation of hope,” the Rev. Florence said then. “For those who fear the people, it is rightly a cause for fear and trembling.”

A new approach to civil rights

If the uprising was a seminal moment in Rochester history, the Rev. Florence more than anyone corralled the burst of energy and directed it menacingly toward the community’s white power structure. He and FIGHT were confrontational by design, unafraid to use the threat of violence as a negotiating tactic.

“It’s just like with Kennedy and Kruschev,” he said, according to Mark Hare and Lou Buttino’s history of the period, "The Remaking of a City." “You can’t have peace until you get the .45 on the table.”

The Rev. Florence’s key ally was Saul Alinsky, known as the father of modern community organizing, who encouraged an aggressive, attention-seeking approach to negotiations. Together through FIGHT they advocated for greater black representation in community agencies, investigation into police brutality and the patronage of black-owned businesses.

The organization advocated first for desegregation in the Rochester City School District, then for improvement of mostly-black schools rather than a change to integrated ones. The change in the organization acronym – the “I” was redesignated to stand for “independence,” not “integration,” in 1967 – was momentous as it had to do with the direction of the city schools.

FIGHT’s most prominent push, however, was for jobs. Xerox and Kodak, still the dominant employers in the city, were first in line. The former agreed in relatively short order to establish a job-training and hiring practice for minority applicants; Kodak proved more resistant.

Starting with its founder, George Eastman, Kodak had long been a bastion of philanthropy in Rochester and viewed itself as a good corporate citizen. “But in Minister Florence,” one reporter observed, “they did not precisely get a little old lady holding out a slotted collection can.”

The Rev. Florence proposed an arrangement in which Kodak would hire and train 500 unskilled men and women, with FIGHT providing recruitment and counseling to the new hires and consultation for Kodak. The company demurred, leading to an explosive year of heated negotiations in which Kodak’s image in the community was badly damaged. Florence warned in early 1967 of the “long, hot summer” to come and orchestrated a massive protest at the company’s annual shareholder meeting in New Jersey, attracting media coverage across the country.

The Rev. Marvin Chandler, a FIGHT founder who was also present at the Kodak negotiations, said the Rev. Florence’s imperative was both political and spiritual.

“I think he really truly felt that this was a prophetic message,” he told Laura Warren Hill. “FIGHT saw (the civil rights struggle) in political terms, but they saw it as a kind of spiritual struggle for hearts and minds. … This had to do with saving souls, in terms of understanding in the black church.”

The impasse ultimately ended with a somewhat anticlimactic agreement between FIGHT and Kodak for certain hiring efforts in the black community as well as the creation of Rochester Jobs Inc., a broader work-training project through which Kodak would hire around 600 of the “hard-core unemployed.”

Several years later came another jobs program, FIGHTON, a black-controlled corporation that manufactured electrical components for Kodak, Xerox and other local companies.

“If you have a job in this town and you're black, you owe it to this man,” Raymond Scott said in 2008. “And he was powerful at that particular point (the late 1960s). … White folks feared him and revered him, at the same time.”

Fighting like crazy

As quickly as the Rev. Florence rose to prominence and power, the five years following his initial resignation as FIGHT president were a period of turmoil and decline. The jobs announcement came at FIGHT’s 1967 convention, marking the end of his term-limited time in office.

After one year out of office he ran again for the presidency in 1968, succeeding after the other main candidate, Bernard Gifford, withdrew. In 1969 and again in 1970, though, he lost twice to Gifford in deeply controversial elections that showed deep ambivalence in the black community to the Rev. Florence’s iron grip on the organization.

The two factions nearly squared off with crowbars and steel pipes on the floor of the 1970 convention. “I thought I was going to get my head bashed in,” Gifford said. The Rev. Florence was charged with criminal trespass and harassment when he tried to physically retake the FIGHT offices.

“He fought like crazy to try to hold on to that job,” Clarence Ingram said. “When he lost the presidency, now he’s a nobody — he don’t have nothing to storm up. Storm and march in your office and threaten you, and all this kind of thing.”

In the following months he was expelled from the Rochester Area Minsters Conference, a group of black ministers, for encouraging “violence and bloodshed,” and was removed from his position at the Reynolds Street church, which felt he had been spending too much time away from the job.

“He had stepped on so many people's necks that they were tired of it,” Scott said. “And so, all of those enemies coalesced and came against him.”

The Rev. Florence and several other followers regrouped and founded the Central Church of Christ. In 1974 it moved to South Plymouth Avenue, where it continues today under the leadership of the Rev. Florence’s son, the Rev. Clifford Florence.

The Rev. Florence’s detractors accused him of being power-hungry and intolerant of dissent, particularly after the tumultuous FIGHT conventions of 1969 and 1970. His ascent in the mid-1960s pushed more moderate black civil rights leaders, particularly those aligned with the NAACP, out of the picture.

“I have not seen them follow through on any issue or cooperate with any other group except on their own terms,” Board of Education President Laplois Ashford said at one board meeting, suggesting that it was more concerned with “making an issue and calling (people) names” than with actual change.

The Rev. Florence responded by leading several hundred people out of the meeting in protest.

“(FIGHT) was a totally anti-intellectual organization,” Walter Cooper said in 2018, still smarting at being labeled “an Oreo and Uncle Tom” by the Rev. Florence in 1965. “It castigated blacks who were educated. … The community is still bearing the scars from that.”

The Rev. Florence’s supporters acknowledge the downside of his abrasive approach but reject the assertion that his motives were impure.

“To this day I would stand on a book, on a truckload of Bibles, and say, ‘I’ve never seen Franklin do anything crooked, never anything wrong,’ Chandler said in 2008. “He had immense, immense integrity.”

A voice at Attica

If Franklin Florence had lost some standing in Rochester by the end of the 1960s, he emerged as an important voice during the 1971 Attica prison riot, where he was summoned as an observer by the protesting inmates.

It was in Attica’s D-yard on Sunday, Sept. 12, 1971, that the Rev. Florence gave what he later called the best sermon of his career. The inmates, he said, had become suspicious that the observers were taking the side of the warden and state authorities, and he sought to reassure them.

Journalist Tom Wickers, another observer, recalled it in his book on the riots: “Some of us were behind the walls and some were not, Florence said, but ‘All of us were prisoners.’ … (He) passionately denounced oppressive social conditions, including ‘an educational system that has done nothing but exploited us, and made everybody rich but made us poor, and made us the criminals, and themselves the victims.’”

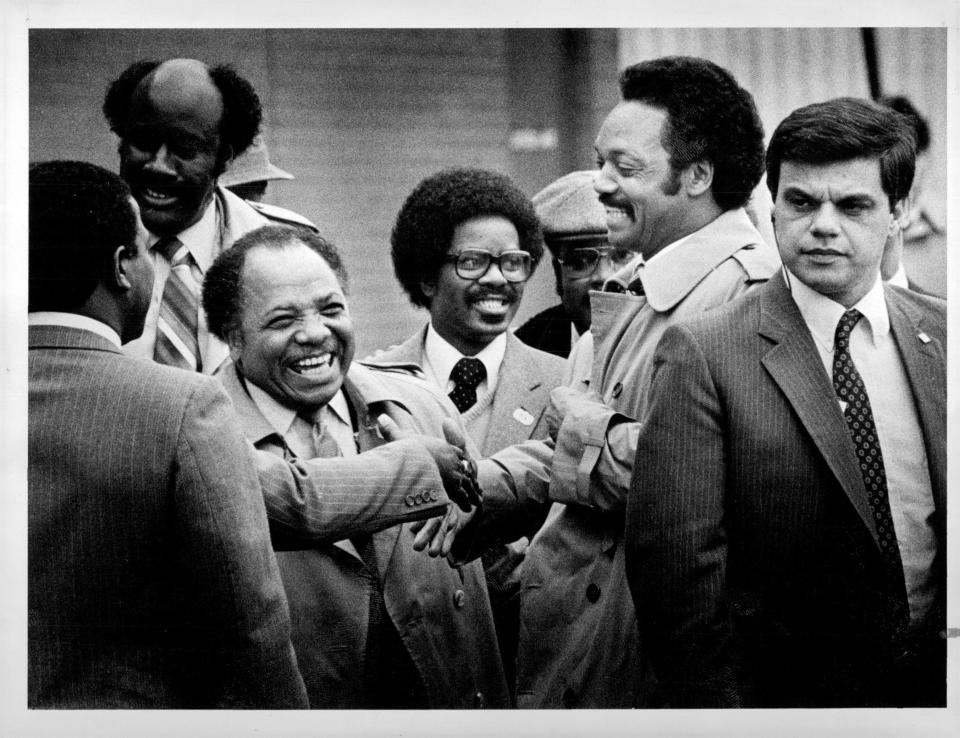

The Rev. Florence ran unsuccessfully for the state Assembly in 1972 on the Liberal party line. After the early 1970s, the Rev. Florence was much less prominent but remained active in several community and political organizations focusing on civil rights, including serving as the head local organizer for Jesse Jackson’s 1984 presidential campaign.

He was an important early member of Action for a Better Community and the Rochester Northeast Development Corp., among other groups. Another part of the Rev. Florence and FIGHT’s legacy are FIGHT Village and FIGHT Square, a pair of low- to moderate-income housing developments. The first remains open, on Ward Street off Joseph Avenue.

His later activism focused largely on police brutality, an issue he saw as a constant throughout his long career in Rochester.

"I don't think anybody says that things are not better in 2018 than they were in the 1950s and '60s," the Rev. Florence told City Newspaper in 2018. "There's been slight improvement, but look what's going on today, man. There's no difference."

The peak of Franklin Florence’s influence was relatively short-lived, but the final impact of his career was not. At a time of changing racial dynamics across the county, the Rev. Florence was the clear face of black power in Rochester. His advocacy around hiring of black people in particular was immensely significant.

“We've never really given this man the accolades that he deserves,” the late Connie Mitchell, the first local elected black politician, said in 2008. “Because he was a tremendous influence on the change that came about within this community—his leadership qualities. And he came at the right time, served the purpose, you know, and then there's a time and place for everything.”

The Rev. Florence is survived by his wife, Mary, four children and many grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Besides his son Clifford, another of the Rev. Florence's sons followed him into the clergy: Franklin Florence II, a pastor in Florida. His daughter, Tiffany Owens, vice president of entrepreneurship and wealth building at the Urban League of Rochester. Another son, Joshwyne Michael Florence, was released from state prison in January after serving 31 years for murder.

Funeral arrangements have not yet been announced.

This article originally appeared on Rochester Democrat and Chronicle: Franklin Florence, civil rights leader, dies at 89