Fred Norris raced into danger to save a downed pilot in Vietnam. Why wasn't he honored?

A loaded pistol in one hand and two ammo clips in the other, Fred Norris sprinted through a muddy rice paddy with bullets whizzing past his head.

It was late 1965 in Vietnam and "hot as hell." Norris and three fellow mortarmen were with a few dozen soldiers conducting a routine search and destroy mission when they walked into an ambush.

Bullets from the Viet Cong sprayed down on them from a brushy ridge above the rice paddy.

Norris and the others hunkered down — sitting ducks in the open field — as they tried to identify the enemy position and how to get to safety. Someone called for backup.

Minutes later an olive drab helicopter skimmed over the horizon and swooped down to the rice paddy. A stream of enemy fire sent the Huey crashing to the ground. Both doors were knocked off by the impact.

The chopper came to rest onto its side, the pilot's legs dangling from one of the openings.

That's when Norris started running.

He wasn't retreating to safety, though, he was rushing into danger.

Sweating profusely and gasping for breath, Norris couldn't see who he was shooting at but he just kept firing. He emptied three clips as he ran, flinging the empty clips to the ground as he reloaded to provide cover fire for the downed pilot. Somehow he made it to the Huey unscathed from the barrage of enemy fire.

Moments later four men joined him and carried the injured pilot — leg and leg, arm and arm — to another helicopter. Norris ran back through another hail of enemy fire to his mortar team.

Fred Norris will be the first to tell you that he is not a particularly brave man. He's no tough guy. No hero.

But in the moment, the way Norris saw it, that pilot was his brother. Lying there helpless in the helicopter, he was family even though Norris didn't know his name.

Ordinary man, extraordinary life

Family is one of the touchstones of Norris' life. So are humility and perseverance in the face of adversity. And integrity.

They're all central to his amazingly ordinary yet, in many ways, extraordinary life: The story of a Black man seeking acceptance in a world where there was always one more battle to fight or another obstacle to overcome.

An abusive father.

Stuttering.

A big-hearted gangster who could have led him down the wrong path.

Trouble at school.

A shooting that threatened his ability to walk, let alone run through a muddy ride paddy.

Not to mention the racism — subtle and overt — that's dogged him for seven decades.

But Norris fought through it all. He kept defying the odds. He kept running into challenges. He maintained his integrity. And he kept building family.

Battles at home preceded war

Long before his days of combat in Vietnam, Norris faced battles at home that no kid deserved.

Fourth & Goal: An IndyStar documentary on the kids everyone counted out

His first memories are from his early childhood in a quiet, Black neighborhood in Evansville, Indiana, where he lived in a small house with his older sister and parents. He still remembers the slight hint of cigarette smoke inside the drably decorated single-story home with wooden floors and wallpaper. Across the street was an apartment complex. Some of his mother's family lived there.

His father worked graveyard-shift custodial jobs. He drank but wasn't a drunk, Norris said, and he could be mean.

“I was scared of him," Norris said.

Norris admired his mother. He wanted nothing more in life than to make her happy and proud. And he wore his love for her on his sleeve like a badge of honor. He also, from an early age, saw himself as her protector.

"He was beating on my mother one night," Norris said. "And I went in there to try to stop him."

His father boxed him like he was a grown man, he said, bloodying him up bad.

"All I was trying to do was stop him from beating my mother with his fists," Norris said. "I ran over there and he damn near beat me to death."

That wasn’t the only abuse he endured, Norris said. His father would heat quarters until they turned red. Then he handed the coins to him. He also poured hot sauce on his son’s food without him knowing. He'd lock him in the bathroom and threaten him with violence if he cried for help.

Norris was only five.

When things got too bad, Norris’ cousin Judith Grinter said, his mother and the children would retreat to her family’s apartment across the street.

Eventually, Norris, his mother, and his sister moved in with Grinter’s family. Nine people packed into the two-bedroom apartment. The six cousins slept in the living room on pull-out couches or on the floor. Norris and Grinter, who was two years older, didn’t care. They were all together — and Norris loved family.

Norris doesn't remember how long he lived with Grinter's family before he, his mother and sister packed up for another move. This time, slipping away while his father was at work, they took a bus to East St. Louis, Illinois. His mother's uncle owned a farm there and his wife had fallen ill with cancer. He couldn't care for her and the land where he made their living.

Norris’ mother, Freda, stepped in to take care of the home, cook and clean.

The move helped Norris escape the abuse of his father, but hardships remained. Norris soon found himself walking the alleyways in white neighborhoods looking for food scraps in trashcans. They were needed to feed his great uncle's hogs. Sometimes, though, the scraps didn't make it to the pigpen.

"The only donut I'd get,” he said, “was the half-eaten one I'd pull out the trash."

Norris had other daily chores, too, including pumping water for the house at the farm's well and collecting eggs.

But as he got a little older, Norris looked for jobs off the farm. Work that came with pay.

A chance to go wrong

One opportunity was caddying for wealthy white golfers. He remembers sitting on a wooden bench outside the Grand Marais Golf Course in East St. Louis, waiting to be picked to caddy. It was 1957; he was 11 and “poor as shit.”

Norris was scrawny and his clothes raggedy, but he caught one golfer’s attention. He still gets emotional thinking about those days — and the kindness of a stranger who could have led him down the wrong path.

"This one guy, man," Norris said, "wouldn't pick nobody but me."

Frank Wortman was the golfer's name. He drove a bright red Cadillac convertible. Wortman was a notorious St. Louis-area gangster. He went by "Buster" and was known for his good deeds towards his Black neighbors.

With caddying for Wortman came money. And with money, Norris could buy himself pants for school. Or a dress for his sister. Even help his mother put food on the table.

During a $6 round of golf, Norris said it wasn't unusual for Wortman to tip him $20. Sometimes more.

"He knew I was poor. He knew what I was trying to do," Norris said. "He knew I was hungry."

The golf course's owner, Bob Bonner, said he's heard all the old stories about the course, including those about Wortman.

"We had Al Capone, Joe Lewis. Everybody used to go there," Bonner said. "The history is rich. It was a place they could do their business."

James Lampley, an East St. Louis neighborhood kid, was too young to caddy with Norris at the time. But he also remembers Wortman, who was known for giving candy to kids.

"He'd come out to his stores or to his clubs at night," Lampley said. "We'd see his red convertible and knew we were getting candy."

Norris and Lampley vaguely knew of Wortman's other activities. Everyone did. But his generosity, especially as a wealthy white man, was infectious. They looked up to him.

It wouldn’t have been hard for Norris to see Wortman lifestyle as a way out of poverty, but there were other challenges to overcome.

A crippling stutter and bullying

Norris stuttered so terribly as a child that he barely spoke.

"It always kept me down," he said. "I could hardly get a sentence out."

There was no help for him, no therapy or speech coach. "They didn't do nothing," he said, "for a negro back then."

Every day at school, Norris had to deal with kids picking on him. His shell grew thick. He never had a girlfriend and didn't go on dates.

"It didn't really hurt 'til teachers started laughing at me too," Norris said. "I'm over here trying to read and teachers are laughing around with the students."

In high school Norris was using a urinal when four white boys entered the bathroom. They were the boys who had bullied him for years.

"They decided they weren't going to just pick on me they were going to beat me up," Norris said.

As he stood at the urinal one of the boys shoved Norris. Urine splattered all over his hands and pants. He was angry and outnumbered. But he'd had enough.

Norris, then 17, turned toward the boy and pushed him back. All four boys charged him.

He grabbed for a straight razor nestled down in his pocket. His father had given it to him for protection during a visit to Evansville. When the boys saw the blade, they ran.

"They tried to fit through the door all at the same time," said Norris, who headed to his locker to hide the blade. He slipped it inside a leather glove.

After the bullies reported Norris, staff searched his locker but didn't find anything. At least not initially. "When they closed the locker, the glove caught in the door," he said. As they opened the locker back up the glove fell out, and the razor tumbled to the floor.

Norris was kicked out of school. No other schools in Illinois would enroll him.

That was the end of high school and, ultimately, the end of his childhood.

Military offered new hope

At home and out of school, Norris was just another mouth to feed. And his mother reminded him of that.

"I understood where she was coming from," he said. "It would be kind of hard for her to support me. I wanted her to be proud of me."

Norris soon found himself walking downtown looking for work. A Marine Corps recruiting sign hanging at the post office caught his eye. He walked into the post office and completed the aptitude test. He passed it. Easy.

"They (recruiters) asked me when I'd be ready to leave," Norris remembered. Without hesitation, he replied: "I can go now.”

Because he was only 17, Norris was sent home to have his mother sign the paperwork. He returned the next day and was on the move again. There were more battles — literally and figuratively — ahead. The first involved the "friendly" recruiter who signed him up for the Marines.

When the bus loaded with fresh recruits reached California, the officer "turned into the exorcist or something," Norris said.

"He went off. He was on everyone."

'Like being born again'

One of his first memories of Camp Pendleton, where he went through basic training, involved the yellow footprints painted on the ground. They helped the new soldiers learn how to line up in formation — and conform to life in the military.

Still hampered by his severe stutter, Norris tried to avoid scrutiny. He stood at attention and tried to get by mouthing replies to commands given to the squad.

"In the Marine Corps if they ask you something you need to answer loud and clear," he said. "I just tried not to talk much."

On the first day of physical training, Norris came face-to-face with the pull-up bar. He'd never even attempted a pull-up, Norris said, and was ''scared as hell.” Man after man jumped up to the bar and completed as many as they could. Some couldn't do one. Norris watched in terror as those men got "tore up" by the training officer.

"The guy scared me so bad I jumped up there and popped off 10 pull-ups before I even knew it," Norris said. "When I got down and he asked me a question, swear to God, I didn't even stutter no more."

Nearly 60 years later, Norris' eyes still well with tears when he thinks back on the experience. Military life helped him overcome a debilitating stutter. It also offered Norris something he had longed for his entire childhood — family and structure.

"It was like being born again," he said. "Like being raised by some old parents."

Shot while home on leave

Norris’ time in the Marines almost ended, however, during a 30-day leave before he shipped out for Vietnam.

For 29 days Norris kept a low profile back home in East St. Louis. He slept, helped out at home and listened to music. But on his last night a friend invited Norris out to a bar.

The bar, called The Foxhole, sat down in the ground. Norris said he was outside when two friends began fighting over family drama. One of the men left. Norris was still outside, sitting between two cars, when the man returned with a shotgun.

The man, who Norris had considered a friend, didn’t say a word. He just fired two shots into Norris' legs.

The other friend jumped and made noise as to get the shooters' attention. Norris pulled himself away, then stumbled down the steps into the bar. Blood gushed from his legs. People started running. Norris was kicked in the head by a man trying to flee.

The shooter was never charged. And to this day, Norris has buckshot embedded in his quads even though doctors told him they'd eventually work themselves to the skin.

The incident prompted a change of plans. Instead of heading overseas, Norris went the Scott Airforce Base hospital in Illinois. Doctors initially told Norris he may never walk again. He spent the next year proving them wrong.

After his release from the hospital, Norris was shipped to Japan for more training before a deployment to Vietnam.

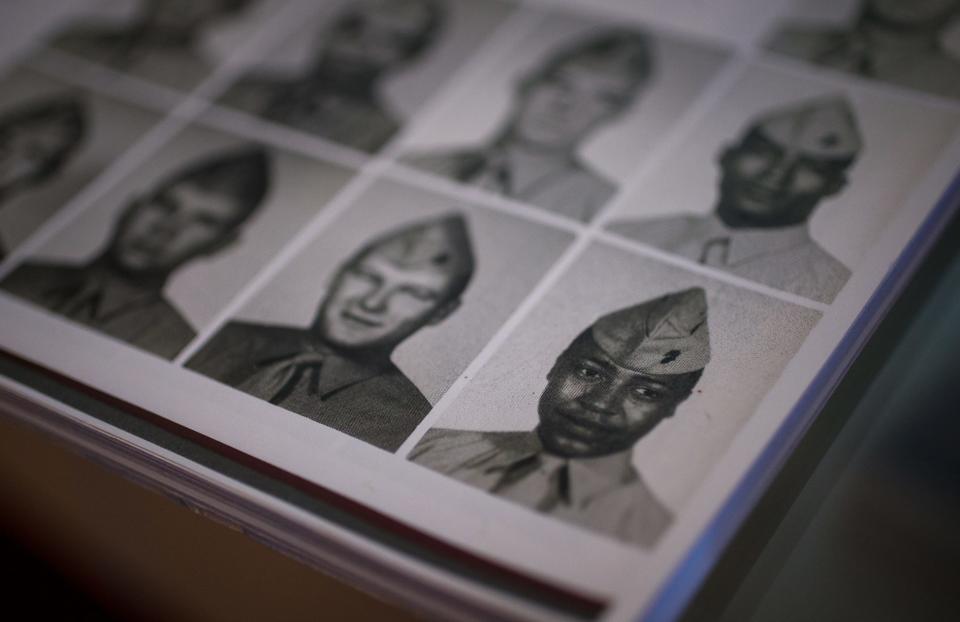

Friendships last a lifetime

Phil Styles and Norris followed similar paths to becoming soldiers. Both were 17 when they enlisted — and both were trying to turn around lives that easily could have veered off in the wrong direction.

"We were both troublemakers," said Styles.

They met at boot camp and forged a brotherhood that's lasted a lifetime. Part of that bond was based on the racism they continually faced, even as they served their country in the military.

Styles recalls fistfights. One involved a man who caked his face with black camouflage paint. He walked up to Styles and said, "Hey, I look just like you!" He also remembers a large picture of the Ku Klux Klan hanging on a bulletin board in the squad bay.

"These are the things we went through on a regular basis," Styles said. "Completely uncalled for."

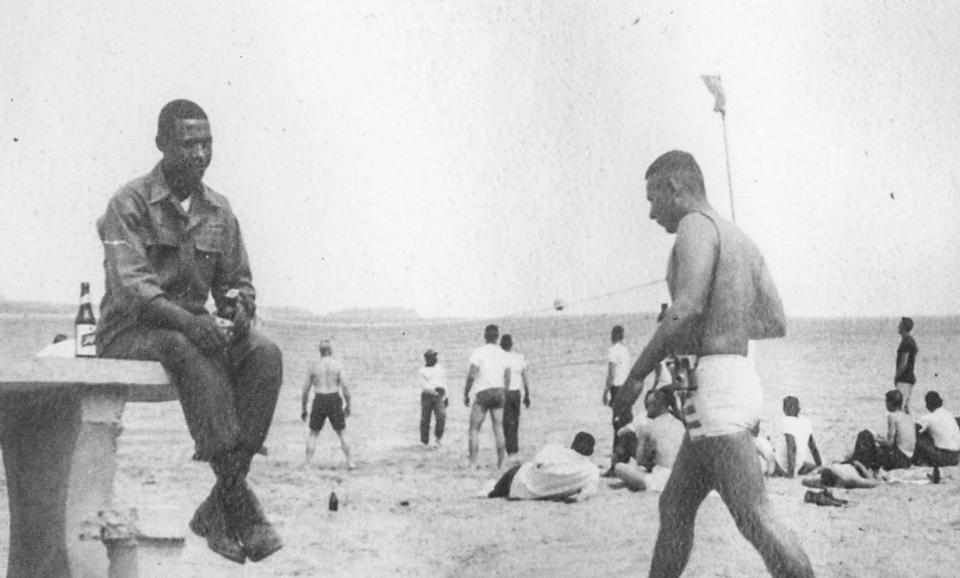

Norris and Styles reconnected in Japan after Norris was released from the hospital. When they arrived in Vietnam, though, they had more pressing worries than racism. They were immediately immersed in combat. And in those moments, Norris said the color of the man fighting beside you wasn't important. What mattered was whether or not he had your back.

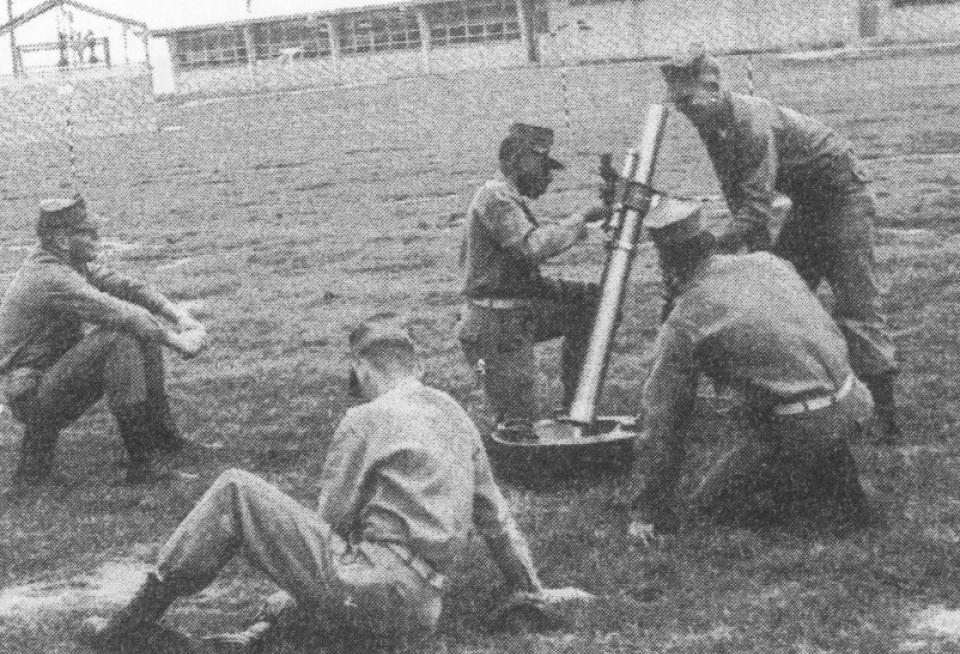

Months of intense fighting

Norris was among some of the first Marines to arrive in Vietnam during a risky amphibious landing in Chu Lai in May 1965. Styles was overhead in a helicopter providing cover.

Their initial mission was to clear and protect the area for a new base and airstrip.

"We had to fight our way up the beach," Norris said. "When they dropped the gates on the boats, they were waiting for us."

Months of intense fighting followed. The land was still raw with rolling hills, rice paddies and forests abundant.

"It wasn't like what you see on TV with big tents everywhere," Styles said. "That stuff wasn't there yet."

There were foot patrols night and day, through bush and small seaside towns. Sometimes they'd be dropped off on missions by helicopter. In May, temperatures averaged 85° with humidity between 70-90%.

Mortarmen carried only a .45 caliber handgun with three clips for self-protection. Anything more weighed them down and made it hard to carry the mortars and ammunition. The mortars alone weighed about 100 pounds.

For food, they'd eat C-Rations left over from the Korean War. They weren't like his mother's country meals, but they did the trick. "When you're hungry,” Norris said, “you eat anything.”

Norris remembers liking the ham and lima beans. And then there was the turkey loaf. Styles said he'd throw some hot sauce on it. Talking about those memories on the phone recently, Norris and Styles laughed about the tiny Tabasco bottles they carried to add flavor to the bland military meals.

But there was little laughter during the missions in Vietnam. Many times when they encountered enemy troops, the Marines were badly outnumbered. And often it was difficult to identify where the hostile fire was coming from. That's what happened that hot day in 1965 when Norris and a small group of Marines wading across a rice paddy suddenly came under fire.

"All hell broke loose, man," Norris said. "All hell broke loose."

'Bullets flying by my ears'

Pinned down by snipers positioned on a ridge overlooking the hillside field, the Marines called for air support. Soon, Huey helicopters appeared. One chopper was hit as it approached and crashed not far from where Norris' mortar crew had taken cover.

Norris didn't think, he just acted on instinct

"I jumped up from my gun and I run about 150 feet," he said. "They started shooting at me and I started shooting back. I don't know what the hell I'm shooting, I'm just trying to get between them and the pilot."

Much of what happened in those moments is a blur today, Norris said, the details lost to the chaos of combat and the haze of passing years. He remembers running through the sloppy mud, a mix of water and buffalo manure, and the humid air. But mostly he remembers "the bullets flying by my ears."

When he reached the helicopter, Norris said the injured pilot had a .38 caliber pistol in a shoulder holster. He tried to give it to Norris. But Norris urged him to hang onto the gun.

"I told him," Norris said, "the situation we're in, you may need that yourself."

After others arrived to carry the pilot to safety, Norris ran back to his post with the mortar team.

"We didn't think you was going to make it," one man told him. "They was shooting at you like a rabbit all the way over and all the way back."

Norris said he's never questioned the snap decision he made to run into danger to help a fellow American.

"I felt good doing it. I felt good saving that guy," Norris said. "The Marine Corps stresses 'no man left behind.' But the Bible also stresses that there is no greater gift than a man who is willing to give his life to save somebody else."

Norris said he wasn't trying to be a hero.

"I just wanted that guy to go home with me that day, man," he said. "He was white and I'm Black, but it didn't make no difference out there."

Heroics went unrecognized

Back at camp word quickly spread about the heroics of the 18-year-old Norris.

His buddy from boot camp, Styles, wasn't on that mission. But he soon heard about it. He was happy for Fred. He was even happier his friend survived.

Styles said he and others at the camp talked about what medal Norris might receive. Some speculated it might a Bronze Star, which is given for heroic or meritorious service in a combat zone. Nearly 60 years later, they are still wondering. Norris' actions in the rice paddy that day were never honored by the Marines.

He didn't think about it at the time, but Styles said he and others can't help but wonder if Norris was slighted because he was Black. A shiny medal or framed commendation aren't important to Norris now. Still, he admitted it hurts that he was never officially recognized for what he did.

"I ain't no glory seeking, glory hunting — but if a person do something, at least give them credit for doing it, man," he said. "I deserve the same break everybody else got. Ain't no monetary gain. It's just prestige and integrity."

Different battles back home

Norris returned home from Vietnam after what he described as "469 days of brutal hell." Like many returning servicemen, he wasn't ready for the reception from fellow Americans weary of the unpopular war.

It started at the airport soon after he arrived back in the U.S.

Norris had traveled for hours, with stopovers and delays. He was anxious to be home, but nervous about what he'd find there. When his plane finally touched down in St. Louis, a woman approached him in the terminal.

"Spit right in my face," Norris said, "and called me a baby killer."

He was hurt and confused. Norris believed his service was honorable. He'd risked his life numerous times. He'd seen friends wounded and die.

But he pushed aside the heaviness of the woman's hasty comments. He had a new mission. Norris hadn't seen his mother in more than a year and couldn't wait to be with her.

"I didn't even tell her I was coming," Norris said. "Surprised her real nice. It was a glorious time."

He said she hugged and kissed him, and held him tight. Then she cooked him one of those big country dinners he enjoyed so much.

"I guess I worried her to death over there," Norris said. "She was determined I wasn't going anywhere else."

Her health was failing, too, so Norris took a post at the Marine Barracks in Norfolk, Virginia. He traded his mortar and fatigues for a job standing guard in a dress blue uniform. Norris served for nearly seven years before being discharged in 1969.

"Went in at 17, came out at 24 a brand new person man," he said. "And I'd do it again."

'Freedom' comes amid more racism

Following his discharge from the Marines, Norris landed a job with the railroad. He started as a "grunt," doing labor on a construction crew. He worked hard and eventually was promoted to a job as a conductor.

"It was freedom, man," Norris said. "I was a conductor, a big deal for a Black man."

But he still found himself fighting racism. In Texas, it was so prevalent Black employees had to eat in the caboose. And in Illinois, Black workers would only go into some towns as a group. It was too dangerous, he said, for a Black man to be alone after dark — even into the 1970s.

Norris lived with his mother in East St. Louis while working for the railroad. Her health was deteriorating and with the help of his sister, who worked as a nurse, they looked after their mother until her death in the late 1970s.

"She didn't have to work for nothing," he said. "We knew what she went through trying to raise us."

In 2002, his sister died following a battle with cancer. Norris retired from the railroad the following year after 26 years as a conductor.

Alone again, he was back searching for family. Norris had a daughter in St. Louis and a son in California, but it was three half-brothers (they have the same father, but different mothers) in Indianapolis who convinced him to come back to Indiana.

Never escaping war

Norris met his wife, Paula, in Indianapolis. They've been married 20 years and live in a cozy, single story home on the eastside of Indianapolis.

"A beautiful soul, man," Norris said. "She be on my ass a lot but she keeps me in line. She takes care of me. Couldn't find a better woman nowhere in the world."

Now 76, his feet are failing due to complications from exposure to Agent Orange in Vietnam. He had a partial foot amputation in 2015, and lost some toes on the other.

Norris uses a walker and wheelchair to get around. Even standing up has become a chore. He receives weekly infusions through an IV in his arm at Richard L. Roudebush VA Medical Center in Indianapolis to help the infection in his legs and feet.

He said the VA is preparing to place wood floors in his home to make it easier for him to maintain mobility. And he's learning to drive with hand controls after the loss of feeling in his feet cause him to crash through his garage wall.

Norris also struggles with post-traumatic stress disorder related to his service. Flashes of the war periodically invade his brain, especially at the hospital. "In the middle of the day, sweats and everything," he said. "Out of nowhere, I don't know why it happens."

The hauntingly vivid memories and his ailing body are regular reminders that he will never escape the complications of a war that ended 47 years ago. He has anger problems as well. When they crop up, he counts backward from 15 to 0 to regain his composure himself.

"By the time I get to 1," he said, "I'm usually pretty well calm."

Most of the time, he said, the anger is triggered by thinking about the war. And he thinks about it a lot. It's hard not to. But, until recently, he never really wanted to talk about it.

He kept the emotions — and the stories — bottled up for years.

Still, Norris stayed in touch with his old wartime buddies such as Styles. They talk on the phone regularly. Sometimes they laugh, but other times their conversations end in tears. It's not always because they're sad but rather, deep down, they know their days are numbered and they fear their stories will be forgotten.

Something better than a medal

Over the years, Norris said, people have asked if he ever pursued a medal to commemorate his actions in Vietnam. He never did. Never even gave it much thought, he said, let alone looked into the paperwork.

As he grows older, Norris said, he just wants people to "look back and say, 'Hey, he was there when it counted. I know I can count on him.'"

He doesn't need a medal for that, though. And besides, he's got something else even more valuable. It is an apt reminder of where he came from — and of the integrity and courage that pulled Norris through the long series of challenges that shaped his life.

That reminder dangles from the gold chain necklace draped around his neck: An inch-long dagger with the letters USMC inscribed on the silver blade. The knife stands out — hanging directly over his heart — when he wears a favorite black T-shirt that says "Never Forgotten."

As a Marine, Norris remembers the knife as a Ka-Bar. He and his fellow soldiers carried them. They were great for day-to-day tasks such as opening cans, digging holes and cutting rope. They also were essential for close quarters combat. The 7-inch blade could slice and dice and had a sharp, pointed tip long enough to stab deeply.

In many ways, the miniature version of the Ka-Bar on his necklace is symbolic of Norris' life: From a humble beginning as a rough slab of steel, it was honed by pressure, grit and perseverance — just like Norris was shaped by the hardships and challenges he's overcome.

The finished results, the man and the knife, make him smile.

"Am I proud?" he asked. "I should've been locked up. I could've been shot on the street like so many of the other youths that didn't have no guidance. Yeah, I'm proud."

Tim Evans contributed to this story.

Contact IndyStar photojournalist Mykal McEldowney at 317-790-6991 or mykal.mceldowney@indystar.com. Follow him on Instagram or Twitter.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: Vietnam War: Fred Norris saved a downed pilot. Why wasn't he honored?