Free Press Flashback: A Detroiter put a statue of Satan in his yard and all hell broke loose

For decades, homeowners have installed a variety of figurines in their yards, such as jockeys, roosters, flamingos, turtles, frogs, peacocks, bunnies and gnomes. Catholic homes often featured statuettes of the Blessed Mother, and some Catholic home sellers have buried small statues of St. Joseph in their lawns in hopes of speeding the sale.

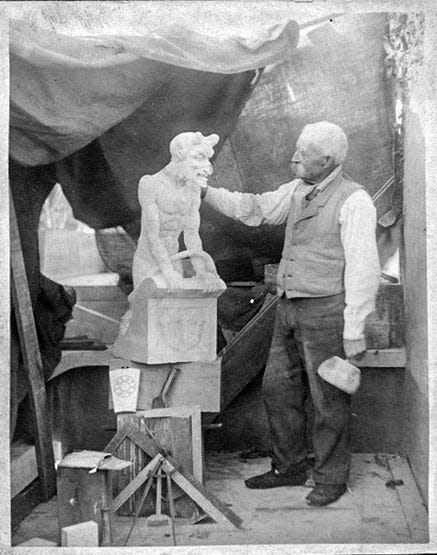

In November 1905, stone mason Herman Menz had a novel idea for a yard ornament.

At his home on the west side of Detroit, Menz unveiled a 14-foot statue that he chiseled himself. It had horns, a tail and cloven hooves.

It was the devil … as in Satan.

Call it what you will — Lucifer, Beelzebub, the Prince of Darkness, the Monarch of Hades, Prince of the Fallen Angels — the statue radiated abundant creepiness.

After its appearance, um, all hell broke loose.

People showed up in droves at Menz’s home; churches organized to fight what they had long prepared for — the sudden appearance of the evil one. There was talk of mob violence, though only a couple of minor incidents took place.

“MENZ DEFIES CHRISTIANITY WHILE REVIVAL STIRS IN CITY,” screamed an all-caps, page 1 headline in the Detroit Journal.

Menacing the devil

Neighbors, agitated to a “pitch of hatred,” called the statue “an insult to the community” and demanded it be torn down. The Free Press blasted the granite devil as a “hideous freak.” Rumors flew that it was “a relic of witchcraft.”

A representative of the Catholic Church in Detroit called the statue “shocking.” He added: “I can hardly conceive a man in his right mind erecting such a monument.”

Kids threw rocks and mud at the statue. A hurled object chipped one of the devil’s ears.

“Lop his head off,” a boy called to his friend one morning as a group of school kids menaced the devil.

Some people recoiled after perceiving the devil projected a silly grin, mocking them with its “evil eye.” A reporter wrote the statue “grinned maliciously.”

Devil fever peaked Nov. 12. Thousands of people converged on the Menz’s home in streetcars, automobiles, carriages and on bicycles. Police stood guard. A reporter wrote that crowds were “hooting, howling and calling for his satanic majesty to appear.”

Menz “has become the most sought-after man in the city,” the Journal reported.

Another Free Press Flashback: George Plimpton's 1963 tryout with Detroit Lions inspired book, movie

A neighbor voices support

Devil worship, while ho-hum today, existed far underground at the turn of the 20th century. Many visitors at Menz’s house gazed in stunned disbelief at the fork-tailed gargoyle, astounded that someone would be so brazen about displaying the emblem of such a forbidden belief.

Menz didn’t appear to have a lot of supporters in Detroit, but one lived next door. “Let him have his statue,” said Robert G. Young. “The only difference between Menz and a lot of other people is that he puts the sign of his beliefs out where everybody can see it. He has been a good friend.”

Menz, 71, was a German immigrant who ran a masonry business at his home on Stanton Street at McGraw Avenue, near today’s interchange of Interstate 96 and I-94.

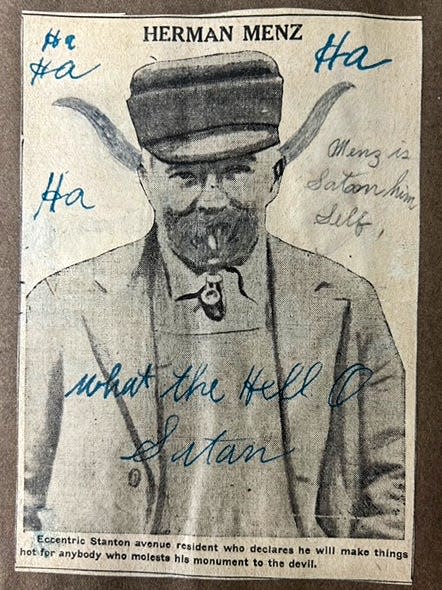

He was described as short and sturdy. People considered him eccentric even before the statue, like during the previous summer when Menz protested revival tents in his neighborhood. He claimed the singing of religious hymns made him nervous.

‘Sheep pens’

Some Detroiters referred to Menz as a “Darwinian,” and not in a good way. They believed his devil statue was the manifestation of a free-thinking modernist who probably had other dangerous ideas in addition to evolution and Satanism.

When asked in interviews about the real devil, the legendary horned fellow who is said to be the source of all evil in the world, Menz made his feelings clear. “He is my friend,” he said.

Menz called churches “sheep pens” and said he didn’t believe “a word of the Bible.”

He also taunted the clergy: “The ministers and the priests ought not to complain. The devil is the best friend of them all,” Menz said.

Unlike many of his tormentors, Menz had a sense of humor. He seemed to enjoy the attention. With a bemused smile, he patrolled his yard with a long stick, and at times blocked the view of the statue from the street, charging 10 cents admission to see it.

“Where is your devil?” a neighbor asked one day.

“In purgatory,” Menz joked.

He added sarcastically that he had purchased a rosary and planned “to pray him out,” in the Catholic tradition.

On another occasion, Menz decorated the statue with a red, white and blue bow around its neck. He called it a “Yankee devil.”

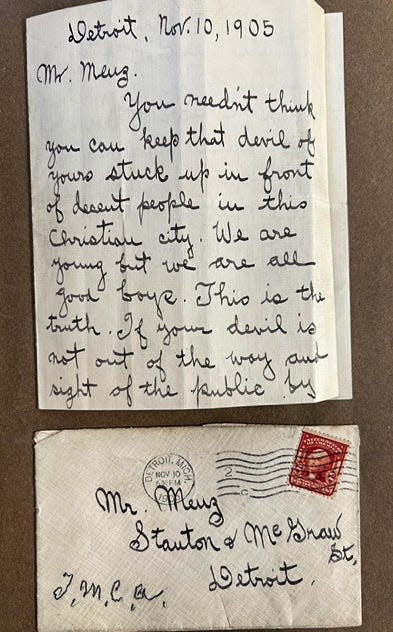

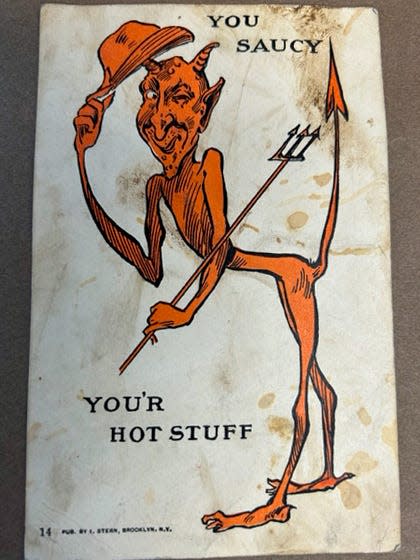

Menz’s next-door neighbor was not his only supporter. A scrapbook in the Labadie Collection of social protest literature at the University of Michigan contains a sampling of sympathetic letters, telegrams and postcards from Utah to Denmark.

One of the themes contained in the communications is that devils — as well as gods — are social constructs that human beings have created over the centuries to meet their own needs.

In fact, a Latin inscription on the devil statue’s 8-foot base, translated, proclaimed: “Man is not created, but is developed. God did not make man, but man did make the gods.”

Frank Dvorak, of Chicago, assured Menz there actually were millions of Satan worshippers in the world and they had his back. “Down with religious fanatics and up with the truth of nature,” he wrote.

“Long live the devil!” said Tobias Sigel, a Detroit physician.

James E. Scripps, founder of The Detroit News and a major player in the establishment of the Detroit Institute of Arts, drove up to the Stanton Street home in a two-seat car one night and offered to buy the stone devil. He called it “a work of art.” (There is no evidence Scripps practiced Satanism.) Menz refused to sell it.

Critics got in touch with Menz as well. “I am writing to tell you Jesus died to save you,” said an anonymous correspondent from Alexandrine, Nebraska. A writer from Garner, Iowa, assured Menz, “You need not spend eternity in hell.”

The controversy waned as winter set in. Menz eventually appears to have lost the statue because of a debt, and it was purchased by the operators of Electric Park, an amusement park at East Grand Boulevard and Jefferson. They placed the devil in the middle of a maze called “The Inferno,” the title of Dante’s 14th-century poem about a voyage through hell. By 1908, though, Electric Park had second thoughts: the owners decided the statue had become a bad-luck “hoodoo” and returned it to Menz.

Beyond his provocative landscaping, Menz was a gadfly at Detroit city hall, and he ran twice unsuccessfully for city council, advocating such progressive causes as municipal ownership of the streetcar system and public utilities. He also wanted the city to tax real estate owned by churches.

He eventually moved to Farmington, where he died in 1919.

Menz’s later years were not newsworthy. It is not known whether he re-read the numerous letters he received during the height of the devil controversy, like the comforting message from C.F. Hull in Spanish Fork, Utah.

“How is the health of his satanic majesty these days?” Hull asked. “If the climate becomes too heated out there, you might send his holiness out this way.”

Bill McGraw is the editor of Free Press Flashback.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Detroiter Herman Menz put Satan statue in yard and hell broke loose