Free Press Flashback: Meet the women who swam 24 miles across Lake St. Clair in 1927

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The Detroit Women’s Aquatic Club made heroes and headlines on Aug. 13, 1927, when it hosted a 24-mile swim for amateur female swimmers from the Old Club on Harsens Island at the northern edge of Lake St. Clair to the Detroit Yacht Club on Belle Isle.

The first two finishers were Aquatic Club members and twin sisters. Twelve of the 17 swimmers failed to finish the grueling route that was then called the St. Clair Channel.

The winner, 19-year-old Edith Fehr, spent 11 hours and 22 minutes in the water. Weak upon finishing, she was carried to a dressing room in a stretcher made from a blanket. Fehr’s sister, Evelyn Armstrong, who recently had a baby, was close behind Fehr the entire swim and finished seconds later.

This result was an upset. Armstrong usually finished before her sister and was the predicted winner. Edwardina Kranich and Billie Paananen, also Aquatic Club members, finished approximately a mile behind the twins.

With this extraordinary athletic feat, the swimmers invited the fame afforded to international sports hero Gertrude Ederle.

Ederle became a global sensation after she swam the 21-mile English Channel in 1926. As Ederle made a fortune, she also made famous the front crawl stroke and the close-fitting, non-dragging, skin-showing bathing suit.

The 24-mile swim in the St. Clair Channel was thus a group exercise in imitating and outperforming Ederle by 3 miles.

Media attention, too, was Ederle-esque. Ederle was paid by newspapers in exchange for exclusive coverage of her English Channel swim. The Chicago Tribune also egged on Ederle with a $2,000 bonus if she made it across the Channel. Papers around the world covered her successful finish. Ederle was one among other fashionable feminine sports heroes of the day featured in newspapers, such as pilot Amelia Earhart and tennis player Helen Willis.

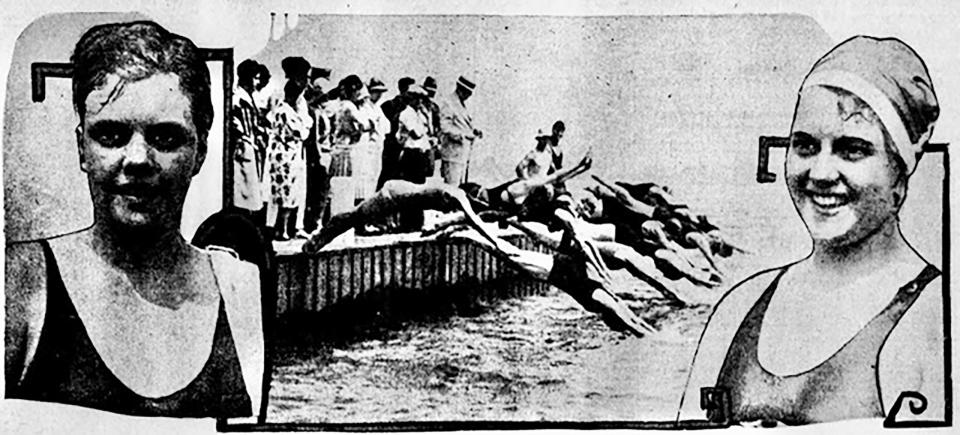

The 24-mile St. Clair Channel swim also made the papers. The day after the women splashed in the lake and the river, photos of their dramatic finish splashed across the front page of the robust Sunday sports sections of the Free Press and Detroit News. The winners were pictured wearing the Ederle-style bathing suit.

More: 7 athletes who swam across Lake Michigan: From Ted Erikson to Elizabeth Fry

The Free Press reporter, Stanley Brink, was a splendid witness to this spectacle. He marveled at the boisterous crowd at the swim’s finish on Belle Isle. He gushed at the remarkable athleticism, resilience and good sportsmanship of the women who both completed and attempted the swim.

“Whistles tooted from the yachts moored at the dock, saluting cannon exploded, cheers tore the air, and a wild chorus of feminine and masculine cries of congratulations marked Miss Fehr’s arrival,” he wrote.

“Each yachtsman who had a whistle tried to outdo his fellows and the greetings might have been one reserved for Lindbergh or President Coolidge had either the chance to visit the club,” Brink observed.

Brink was no Pollyanna though. He painted a picture of the obvious to anyone suspecting it. The swim was punishing: “Miss Fehr finished on nerve. Attendants heard her babbling to herself at times during the last mile when every stroke was torture. She was a very weary young woman and only an iron will expressed in mechanical stroking carried her on.”

Brink showed he was particularly with it when noticing that most of the winning swimmers used the in-fashion front crawl but that “Miss Paananen varied her locomotion by using the breast stroke.”

Brink also made more than honorable mention of the women who dropped out early and “showed signs of exhaustion long after they had been removed,” but somehow nevertheless made it to Belle Ise to cheer on the swimmers who remained in the water. “Each girl … refused to go home, as she was determined to see which of her compatriots would win.”

Free Press Flashback: Meet the man who served as the ‘voice of the Detroit River’ for 58 years

The effort of the fifth finisher, Marion Bland, did not officially count. Bland swam ‘just for the fun of it,’ that is, “if you can call a 24-mile swim fun,” Brink remarked. As a professional physical trainer, Bland was disqualified from winning a prize in a contest marked for amateurs.

Although Amy Walker did not finish the swim, she was awarded a prize for remaining in the water the longest —more than 14 hours — before exhaustion overtook her. She had run into a squall near Windmill Point, 2½ miles from the finish.

Francis Kraft dropped out early because of an arm cramp.

An otherwise experienced Detroit swimmer, Dorothy de Caussin, suffered a knee cramp early in the swim but nevertheless completed 15 miles of the course. “I’ll finish next time,” she vowed.

Beatrice Gralka hung on for 14 miles.

Jean Laux would have taken fifth place had she not dropped out at 20 miles.

These women were certainly good sports. Not all the swimmers were predicted to finish.

“Various experts stated before the race was half over that no more than five would finish. For once the experts were half right,” Brink quipped. “Five did finish, but as Marion Bland’s entry was unofficial, the total stood at four.”

The women, advantaged when swimming with the current, were also coated with grease as Ederle had been for her swim across the English Channel. Still, the Detroit women struggled with the water and found it “hard to bunk,” especially those accustomed to swimming in pools, not open water. Some had experience with open water with a faster current.

“It was a tough route and the girls who managed to negotiate the entire distance are not anxious for another one just yet,” Brink explained.

The Detroit River, and its companion Lake St. Clair, had already been a significant environment for competitive swimming. After World War I, while money rolled into Detroit, women’s swimming and women’s sports grew exponentially.

Ahead of its time and on trend, the Detroit’s Women’s Aquatic Club, founded in 1914, was the first women’s swimming club in the United States. In its prime from 1921 to 1931, the club had a University of Michigan swim coach and a membership of 300, with a waiting list.

When a national swimming club held its championship open water swim events in Detroit in 1925, Ederle competed, and the Aquatic Club sponsored a half-mile swim, a 2-mile swim and diving contests.

The Aquatic Club’s sponsoring a supersize event in Detroit, like the 24-mile swim, to rival Ederle’s swimming the English Channel was not just a sports event but also a media stunt. Given the reputation of Detroit as a premiere host for women’s swimming, the well-publicized stunt could even suggest that the St. Clair Channel was the North American equivalent of the English Channel. The twins Fehr and Armstrong could become Ederle’s media twins.

The five women who completed the St. Clair Channel course had swum farther than Ederle in their swimming channel, made headlines in the paper, and Detroit was a model for the nation.

Yet, the 24-mile was the Aquatic Club’s most ambitious event and the last of its kind.

When the Depression hit two years later, the female sports hero would have less cultural support and media coverage. Symbolically, media sweetheart Amelia Earhart went missing in the Pacific.

The Aquatic Club continued to sponsor open water swimming events into the 1940s, however. The first course was from the Edison Boat Club near the foot of Conner Avenue to the Detroit Yacht Club. A later course was downstream with the current from the Detroit Yacht Club to the Detroit Boat Club.

Detroit’s 24-mile swim celebrated the female sports hero and the everyday athlete on location — a symbol of women’s strength in a 1920s post-suffrage era ripe with optimism and promise.

It reminds us of culture-making athletic pioneers foundational to women’s sports and women’s power in the 20th century.

Liz Rohan is a professor of composition and rhetoric at University of Michigan Dearborn.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Swimmers were heroes after 1927 Detroit Women’s Aquatic Club race