Free Press Flashback: Michigan daredevil jumped out of planes and flew like a bird

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When Clem Sohn met his end at a Paris air show in 1937, flailing desperately as he plunged to earth with a pair of defective parachutes, his death was considered tragic but hardly shocking. The winged daredevil, alternately known as “Bat-Man,” the “Human Bird” and “Michigan Icarus,” had been tempting fate for years, masking the danger with an air of breezy confidence.

“I feel as safe as you would in your grandmother’s kitchen,” Sohn said before his final jump, which culminated with him hitting the ground at an estimated 100 mph. It wasn’t the sort of impact the 26-year-old had hoped to make on the world.

Sohn was more than a nervy showboat; he was a dreamer who felt his homemade wings were advancing the science of aeronautics.

“Someday, I think that everyone may have my wings and be able to soar from the house tops,” he explained to a London newspaper in 1936.

His ultimate goal was to create a practical apparatus that would allow someone way up in the clouds — a pilot in distress, say, or an adventurer on a lark — to glide to a landing instead of using a parachute.

Sohn was born in 1910 in the village of Fowler, about 100 miles northwest of Detroit. His youth was divided between the family farm in Clinton County and Lansing, where he attended Eastern High. As a teenager, he took to hanging around the local airfield, where he became acquainted with stunt pilot Art Davis.

Davis ran a small aerial show, one of the many “flying circus” acts then operating across America. He literally took Sohn under his wing, piloting his two-seater plane to 12,000 feet before Sohn would climb out and hurl himself into space.

Jumping with Mile High Wagner

Parachuting was still considered a stunt, not a sport. (The word “skydiving” wouldn’t enter the lexicon until 1955.) In these early years, Sohn specialized in delayed drops, waiting until the last moment to pull his ripcord. To make dangerous stunts even more compelling, sometimes two people would jump out of separate planes at the same time, engaging in a game of “chicken” on the way down.

Detroiters’ first look at Sohn was on July 30, 1933, during a Sunday air show at Wayne County Airport. Sohn and Detroiter Wayne “Mile High” Wagner, dubbed the “human comets” by the press, bailed out at 10,000 feet and were still hurtling as they got to within 800 feet of the ground.

The 2-mile plunge had spectators holding their breath. Then billowing chutes appeared, and the pair floated down to “a burst of relieved applause,” reported the Free Press. “The suspense for the 20,000 spectators had been terrific.”

Jumping out of an airplane was one thing, controlling what came after was quite another. Some early practitioners, like Sohn, were discovering that by making swimming motions in the air they could manage their descent, as well as make more accurate landings.

“I found out that I could actually slow myself, go into a dive, and flatten out again, and I wondered whether I could not do better with a set of canvas wings,” Sohn told a Lansing reporter. “And there you have the origin of my bat wings act. I found they actually did work.”

Flashback: Remembering Detroit’s last pro football champs – the Michigan Panthers

A smoke bomb between the legs

Sohn unveiled his wings on Feb. 27, 1935, in a 12,000-foot jump over Daytona Beach, Florida. While slowly counting to 75, he did several loops, sharp banks and some gliding before opening his chute at 2,000 feet. In subsequent jumps he continued to improve the length and complexity of his aerial performance.

Canadian correspondent Matthew Halton described Sohn’s contraption:

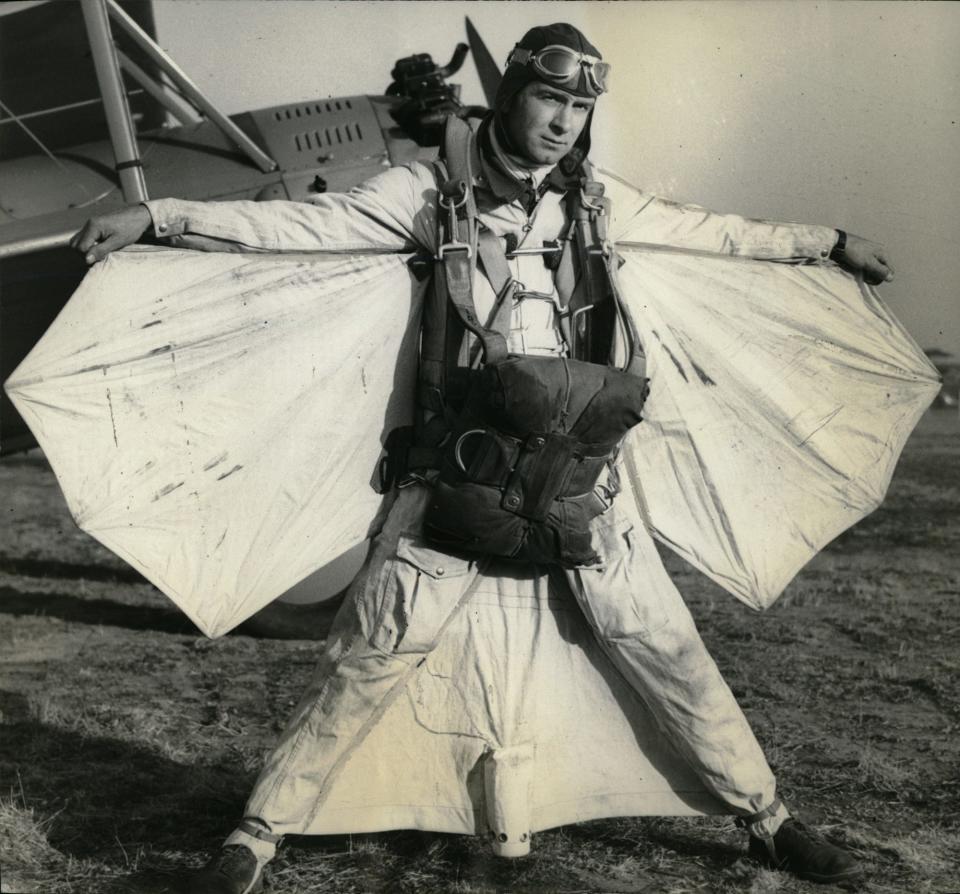

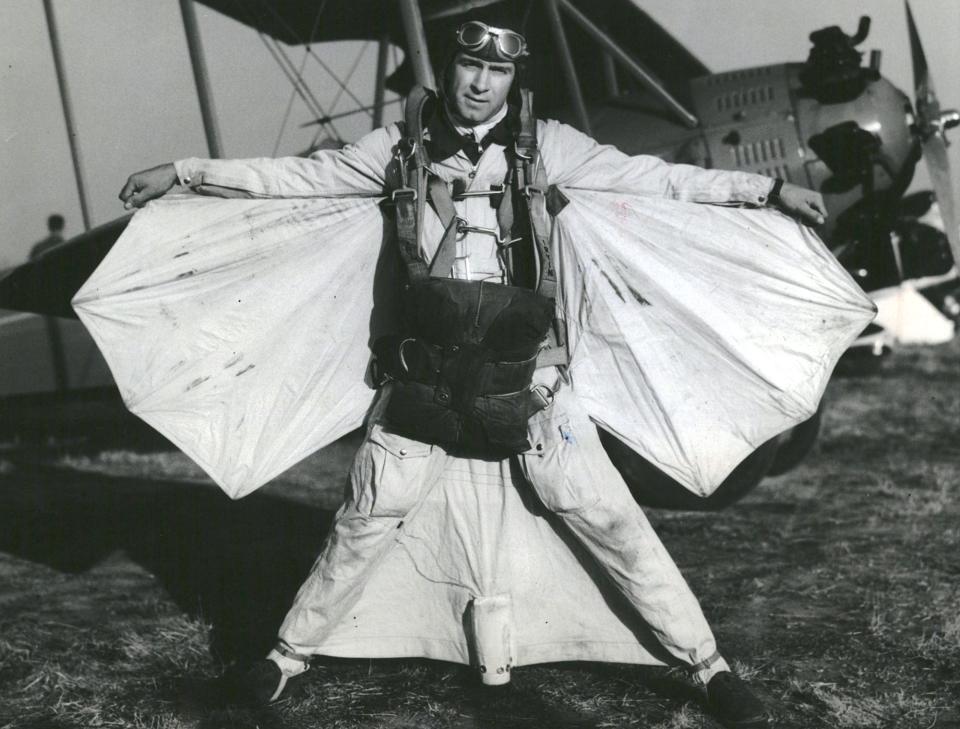

“His wings are nine feet from tip to tip. They are made of metal struts covered with strong cloth, and they work on the umbrella idea. The wings are strapped to the waist, with a metal bar, and they have a handle on each tip, which he holds in his outstretched arms.”

The metal bar at the waist relieved some of the strain. A triangle of sturdy cloth fastened between his waist and each ankle acted as a giant fin. With his wings and fin, he could steer himself as easily as he could a car, Sohn said.

“It’s fun, but it’s awful hard work. Imagine holding those wings out, and keeping your legs wide apart so the fin will work! When I get to the ground I’m so tired I can hardly stand up,” he told Halton.

The parachutes weighed 75 pounds, quite a load for a 140-pound man.

Sohn would jump head-first, wings folded at his side, before setting off a smoke bomb fastened between his legs. This allowed spectators to follow his progress as he opened his wings, leveled off and then began his antics looping, climbing and maneuvering in all directions.

After several minutes of zooming across the sky, he’d finally pop his chute at about 1,000 feet and flutter back to earth, like a dropped handkerchief. It was the ultimate in performance art.

Sohn’s “sky-skiing” was a hit at county fairs and air shows across the country. Businesses came calling, growing his fame and bank account. Chevrolet hired him to publicize a plant opening and new model introductions. In 1936, a London newspaper sponsored a series of jumps at $1,000 each. That promotion ended prematurely when he crashed into a parked car on his seventh jump.

The final flight

The following year, Sohn agreed to headline an air show outside Paris. Ironically, a like-minded predecessor had tested a similar device 25 years earlier — with catastrophic results. In 1912, Franz Reichelt leaped off the Eiffel Tower in a hand-tailored “parachute-suit” featuring folded silk wings. The wings never deployed and the “flying tailor” left a 6-inch-deep impression in the ground.

On April 25, 1937, as tens of thousands looked on, Sohn jumped from 10,000 feet. After swerving, looping and banking for several minutes, he tucked in his wings and pulled the ripcord of his main parachute.

“It started to open,” said an observer, “then caught in the meshes of his wings.

“The spirited French crowd that had been loudly applauding, suddenly hushed. Through binoculars Sohn could be seen pulling the rings of his spare parachute. It, too, failed to open. Within a couple of seconds, while scores screamed, fainted — and many cried — his body thudded to the ground and buried itself near a grandstand. The original batman had folded his wings for good.”

Sohn’s fatal fall was captured by newsreel cameras (and, like Reichelt’s, is viewable online). His death was front page news on both sides of the Atlantic.

“I’ve been expecting it,” Sohn’s father said.

He was buried in Holy Trinity Cemetery in Fowler, with a pilot friend skywriting “SOHN” above the crowd of mourners.

Although Clem Sohn is hardly the recognizable name he was in the 1930s, some today consider him the unofficial godfather of today’s wing-suit jumping, an extreme form of skydiving with military and sport applications. And a plaque in the lobby of Lansing’s Eastern High reminds students that, many years ago, one of their own once soared high above the crowd: “There are some pioneer souls who blaze their paths where highways never ran.”

Richard Bak is the author of “The Big Jump: Lindbergh and the Great Atlantic Air Race” and other books.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Michigan’s doomed daredevil jumped out of planes and flew like a bird