Freed slaves founded this town. Their descendants fear postal cuts threaten voting rights

To Black residents whose ancestors built this rural town amid cotton fields 50 miles southwest of Houston, 77451 is more than a ZIP Code.

“It’s very important for us to keep our identity. That’s our address, our ZIP Code,” said Mayor Darryl Humphrey Sr., because of “all the fighting and the work that my forefathers did.”

Kendleton began when slaves were freed in Texas in 1865 — more than two years after Emancipation. William Kendall sold them 100-acre plots of his plantation along the San Bernard River south of Houston. Many signed the land deeds with a mark because they were illiterate.

Those first settlers turned Kendleton into a “freedmen’s colony” with its own school, church, cemetery and a mercantile that contained a post office.

As the political fight over recent cuts to the U.S. Postal Service and changes to vote-by-mail plays out across the country ahead of the presidential election, it's highlighting the vital role of post offices in rural communities such as Kendleton, where Black people have long had to fight for the right to vote.

Humphrey, 57, a retired electrical lineman, counts the town’s first mayor among his ancestors. Other Black farmers managed to buy land during Reconstruction but it was often taken — through inflated assessments, tax sales and theft by white farmers. But Humphrey's family kept their land, as did many others in Kendleton. Humphrey grew up attending Juneteenth celebrations at the picnic grounds that drew Black crowds from across surrounding Fort Bend County.

The Kendleton postmaster, like the mayor, school principal and other leaders, was Black. But they operated in a still-segregated South, where since 1889 Democrats called "Jaybirds" handpicked candidates before elections, ensuring they were white.

Local Black leaders braved death threats to file a successful class-action lawsuit, which reached the U.S. Supreme Court in 1953, overturning the whites-only primaries. They renamed a street in town after one of the plaintiffs, Willie Melton, and in 1993 the government erected a freestanding brick post office there with a plaque out front commemorating the landmark lawsuit.

In the years that followed, the post office scaled back its hours and required residents to pay for one of about a thousand boxes even as Kendleton grew. When the government tried to close the post office in 2011, locals protested, lobbied state lawmakers and kept it open. More recently, Humphrey has been fighting to ensure that online orders — and associated sales tax revenue — go to Kendleton. Often mail, including his, is automatically routed to the neighboring town of Beasley. When Humphrey calls customer service, he ends up arguing, "How can I live in Beasley? I’m the mayor of Kendleton!”

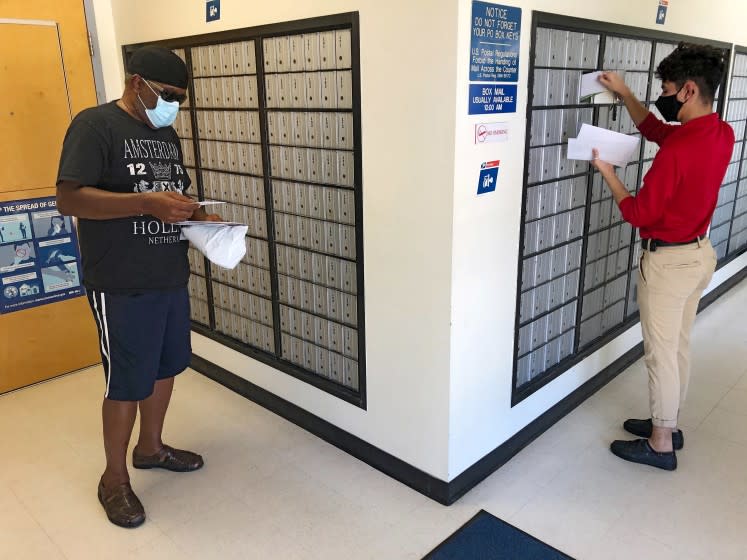

About a thousand people live within the city limits, about 2,000 more in the surrounding area, the mayor said. During the pandemic, Kendleton post office window hours were reduced to two hours — 10 a.m. to noon. Many residents who had started to vote by mail due to their age and the pandemic heard about Postal Service cutbacks ahead of the presidential election and grew concerned.

Humphrey doesn’t trust the Trump administration not to use his post office as a pawn, even after the postmaster general promised this week to suspend any cuts until after the election.

“They tell you something and do something else the next hour or so,” Humphrey said.

On Wednesday, Charlene Contreras opened the Kendleton post office and unloaded mail wearing her usual blue uniform and a mask with the words, “I can’t stay home, I’m a postal worker.”

First to arrive was Trinesha McCullough, 37, a certified nurse assistant who said she usually voted in person at a polling place inside Kendleton Church of God. She said she was worried about older neighbors who could no longer drive, including her 70-year-old mother.

“You’ve got people who don’t have that option” of voting in person, she said before picking up a package containing a Christian self-help book.

Jessie Mae Jackson, 77, said she didn't trust herself to drive even a few miles to neighboring Beasley or Needville. She votes by mail and relies on the Kendleton post office.

“I hope the good Lord it stays open,” she said as she came to pick up her mail.

Jackson moved to Kendleton as a child, picking cotton with her mother. She never learned to read or write. She defines her political affiliation as “righteous” and feels strongly about voting to improve the country.

“It’s divided. God is not about dividing his people,” she said.

Most of those visiting the post office Wednesday were Black, a few white or Latino, including a Republican who planned to vote in person for Trump.

Eugene Torres Jr., 58, a disabled farm and construction worker, said he would vote for Trump again because of the president's support for Israel. Torres sends money to Israeli widows and orphans and on Wednesday received a letter from a Bible translation nonprofit labeled, “Christians condemned!” He wasn’t afraid the upcoming election would be affected by changes to the post office.

“God will handle it,” Torres said, and if anybody messes with the vote, “His wrath will come down on us.”

Arthur Hill, 59, a disabled carpenter in a western snap shirt and KN95 mask, said he had watched Michelle Obama speak this week about how lives are at stake in this election and thought: “She’s speaking the truth.”

“It gave me the cold chills,” he said.

Hill grew up in Kendleton, where his family farmed cotton on land his ancestors bought for 50 cents an acre that’s now “like gold.” He worries about local votes being stolen because “it’s always been a problem of purloining things here.” Instead of cuts, Hill said the government should provide the local post office with more resources ahead of the election.

“They need help,” he said.

On the other side of town, across the railroad tracks, retired postal worker Kathryn Ford was leading a tour of the local museum, including exhibits about the post office, the voting rights struggle and George Floyd (made by her granddaughter, who’s dating Floyd’s brother).

“We have survival skills,” she said, “It’s in our DNA.”

But Ford, 82, who votes by mail, said the postal service had been “handicapped” by cuts, including reduced hours and equipment.

“They’ve removed so much,” she said.

Franklin Crump, 64, a U.S. Army veteran, also worked for the Postal Service for years, at a Houston processing center, before retiring five years ago to Kendleton. He worries postal workers won’t have the resources to simultaneously process mail-in ballots and daily mail.

“I’m thinking they’re going to have to stop this for the ballots,” Crump said as he picked up his mail Wednesday, including a prescription from Veterans Affairs.

“This is a priority,” he said of the medication. “I don’t know how they’re going to handle that.”

Crump was inclined to vote by mail due to the pandemic, “to be safe,” and said he was “waiting for a ballot any day now.”

But he plans to decide closer to the election whether he must go to the polls in person, risking his life like his forebearers to ensure his vote counts.