A fresh look shows Karen Mason's death was suspicious. So what really happened?

NEW LIGHT: THE LIFE, DEATH AND REOPENED CASE OF KAREN MASON

Chapter 4

LATHAM, New York — The investigators sit on opposite sides of a long conference table in an otherwise empty room. Their dark blue suits and COVID masks stand out against the blank, cream-colored walls.

The two men, Samuel Lizzio and Michael Cote, work for the New York State Police, where they make their living probing homicides and other major crimes in the eastern part of the state.

Lizzio takes off the lid of a small cardboard box. He pulls out a white, 3-inch binder with what looks like a ream of color-coded paper inside.

On the spine is a single name, all caps, written in black: MASON.

On a drizzly April day at a suburban Albany police station, Cote and Lizzio provided a rare glimpse at the police investigation into the death of Karen Rew Mason, the 32-year-old schoolteacher found burned and dead in May 1988.

Her body was discovered on the front steps of her father's home in the tiny Adirondack town of Hope, population 400, the same town where Lizzio himself grew up. A third-generation trooper, he was just 5 years old when Karen died.

There's a lot they don't know — typical with cold cases. They can't say whether someone killed Karen, and they can't rule out that it was an accident, as their predecessors had concluded within a month of her death.

But they are confident of this: It didn't go the way police thought it did all those years ago.

They closed the case quickly back then, certain that Karen accidentally ignited herself while fumbling with a glass lantern in the back seat of her car.

"You know, the arson investigators, they were unable to re-create this fire," Lizzio said. "They found it to be not plausible, basically, that what had been explained at the time could have occurred."

The arson investigators are from the state Office of Fire Prevention and Control, which the State Police tapped for assistance 10 years ago as they began to review Karen's case at the apparent insistence of a trooper with nagging concerns.

The result: a dense, 12-page, science-based report that meticulously picked apart the evidence, analyzed the lantern oil and considered what might have happened. It's a pivotal document, the primary reason Karen's case was reopened — and the primary reason it's still open today.

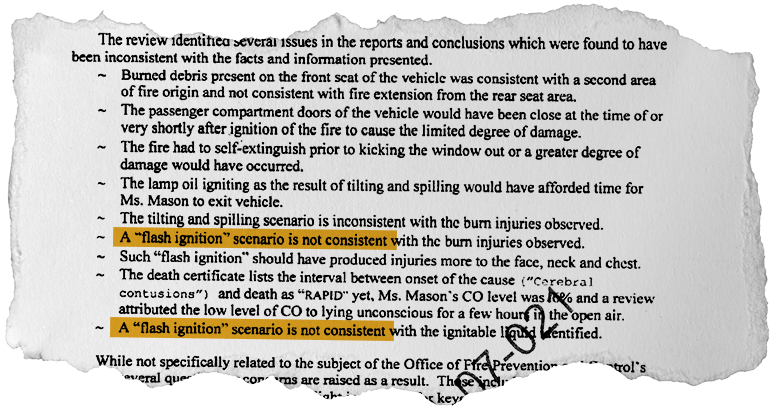

As it turned out, there were "large inconsistencies" in those original conclusions back in 1988. The burns that Karen suffered didn't match up with an accidental burst of flames, the kind of "flash ignition" that police surmised helped lead to her death.

The fire, the investigators found, was likely the result of a "deliberate act."

"These inconsistencies, and a comprehensive review of the materials presented to this agency, would indicate more of a deliberate act in the ignition of the fire," arson investigator William McGovern wrote in the report.

54 death-scene images

McGovern was assigned to the case at the request of State Police Investigator Daniel Stephens, who was performing a review of the circumstances of Karen's death.

McGovern was tasked with assessing a trove of evidence and reports — including 54 images of the death scene and Karen's autopsy, her death certificate, various documents laying out the original police narrative and evidence, a chronological timeline of the events, toxicology reports and a laboratory analysis of the lamp oil.

Subscribe

Support local journalism

Ultimately, his job came down to determining whether the original police theory for Karen's death held up to scrutiny.

In many ways, it did not.

In 1988, investigators concluded Karen had arrived at her father's Adirondack home in the middle of the night, while it was dark. Somehow, she locked herself out of the house.

That's when police believed she went to her car to search for her keys, attempting to light the oil lamp in the back seat for additional light.

"She placed her glasses on the rear deck, lit the lamp and possible (sic) tilted it spilling some fuel causing a flash ignition," police wrote in a 1988 report.

A "flash ignition" is a scenario in which the vapors from fuel mix with the air and are ignited when an open flame is lit.

Ruling out flash ignition

But the arson investigators' report pointed to several reasons why a flash ignition wasn't likely. Among them was the type of lamp oil discovered at the scene.

Parts of the report were redacted by state officials before it was released under the Freedom of Information Law, including the specific type of oil or fuel found at the scene.

The unredacted portions of the report, however, make clear the liquid was combustible, not flammable. A flammable liquid, like acetone, would have a flash point — that is, the lowest temperature needed for the type of ignition police suspected — of less than 100 degrees; a combustible liquid, such as kerosene, would have a much higher flash point.

To put it in plain English: It would have had to have been more than 100 degrees in Karen's car for a burst of flames from a flash ignition to have occurred, based on the lamp oil found.

On the night Karen died, temperatures in that part of Hamilton County dipped into the 30s.

The lamp oil was found on the wick of the lamp, as well as Karen's T-shirt and tote bag.

That type of combustible liquid — whatever it may have been — would have had "slow and lazy flames" as it burned the cloth, which would have acted "very much like a wick," McGovern found.

It would have produced "significant amounts of smoke and soot," he wrote, much like the smoke and soot that covered the car windows and invaded Karen's nose and trachea.

And the source of all that smoke and soot, McGovern concluded, wasn't a fire.

It was two.

A quick conclusion

After her body was discovered, police quickly ruled Karen’s death a tragic accident. Twenty years later, nagging doubts remained.

A 'deliberate act'

Police at the time surmised Karen must have been in the Oldsmobile with the doors closed at the time she tried to light the lamp, or at least shortly thereafter. The broken rear passenger window suggested she kicked it out to escape.

The damage to her car suggested as much: While her seats were singed and burned, it was clear they weren't totally engulfed. That meant there wasn't enough oxygen to keep the fire going, hinting the doors were shut and the windows rolled up.

The arson report generally backed up that assertion. But it homed in on a key point.

Photos of the scene clearly showed there were two separate areas of fire damage in Karen's car. The rear seat was burned, yes, but so, too, was the front seat, albeit significantly less so.

It all suggested there were separate fires in the car — one started in the rear seat; another started in the front. That wouldn't have been the case with a burst of flames from a flash ignition.

"Burned debris present on the front seat of the vehicle was consistent with a second area of fire origin and not consistent with fire extension from the rear seat area," McGovern wrote in the report.

Examining the injuries

Karen's injuries provided even more clues.

Had the vapors from the oil burst into flames when she tried to light the lamp, Karen would have likely suffered significant burns to her face, her neck, her chest — anything that was facing the source of the flame, the arson investigators wrote.

But that wasn't the case. The front of her torso showed no damage at all, according to the report. The image on her silk-screened T-shirt — the one Keith Gaulin, her boyfriend, said belonged to him — was still intact.

Karen Mason's story

Explore the events of Karen's life and the investigation into her death in this timeline.

Her arms, forehead and nose had second-degree burns, as did the right side of her face and parts of her back. The left side of her face didn't show signs of burns, aside from some soot and a small injury over her left eye.

Most of the burns Karen suffered were to her back and upper extremities. They were more consistent with someone who was tipped over to their left side as the fire burned — not someone who was sitting upright, lighting a lamp, the report said.

And Kearney Mason learned another detail from an officer he used to visit from time to time: Karen's fingernails were broken.

"He said that she had broke her nails in her purse looking for probably keys or another set or something," he said.

Armed with the arson report and what they know about the case, Lizzio and Cote are unwilling to rule out any theories about what may have happened to Karen that night.

Except, perhaps, for one.

Could it have been suicide?

The police investigators know, from numerous interviews with Karen's friends, that she was upset by a May 5 hit-and-run crash into a Glens Falls home.

Panicked by the possibility that the incident could affect her teaching job, she went along with a plan to ditch the 1977 Buick in a patch of nearby woods. The next day, she reported the car stolen, an act that friends told investigators was not in keeping with her character.

Investigators know she was going through a divorce, and all the stresses that come with it. They believe, based on interviews with her boyfriend, Keith Gaulin, that she abruptly left for her father's Hope home in the middle of the night.

Is it possible that Karen Rew Mason — the hyper-organized class salutatorian turned schoolteacher who was starting a new chapter in her life — could have killed herself?

Neither police nor Karen's surviving friends appear willing to entertain the idea.

"I say no," Lizzio said.

He points to the brutal conclusion in the medical examiner's report from 1988: That Karen died as a result of brain contusions caused by a fractured skull, which itself was caused by "running while burning."

"In my experience, I've never seen a suicide like that before," Lizzio said.

Cote added: "That doesn't fit her character at all."

Karen's friends and colleagues agree.

"I don't think she'd ever do that because she could never — she loved her mother too much. She would never put her mother through that," said Pam Driscoll, Karen's lifelong best friend. "And I don't — she couldn't be a disappointment to her father. Absolutely not."

Keith, Karen's boyfriend at the time of her death, said investigators have asked him about the possibility of suicide when they questioned him in recent years.

"The troopers that came two years ago, they asked me if I ever considered Karen committing suicide," Keith said. "I said, 'Absolutely not.' But in all honesty, I had never thought about that. She was very happy."

Kearney Mason has a rather bizarre theory for Karen's head injury, one that traces back to their time in Arizona when Karen had gotten a terrible sunburn.

"She kept saying, 'Hit me over the head and knock me out.' I would not," Kearney said in the recent interview. "Next day was better. From that incident I have deducted it possible she did it just to stop the pain."

A battle over her will

Karen's untimely death quickly gave way to a scramble to distribute her possessions, a battle that court documents suggest led to tension between her parents and her estranged husband.

On Feb. 20, 1987, Karen Mason had crafted a will.

She was married to and living with Kearney Mason at the time, and the document reflected that. It made clear that, if Karen were to die, the vast majority of her property would be bequeathed to her husband — including the house they shared in Hadley.

The next year, when Kearney and Karen had separated, she had begun working on a new will, one that would have accounted for their impending divorce. She had been working on it when she visited her father in Florida in the weeks before her death, according to Edna Rew, Karen's stepmother.

After her untimely death, attorneys for Karen's parents pushed the Warren County Surrogate's Court for more time to locate a newer will, and they were given until Aug. 10, 1988. But they never would find a copy of the new will, and Warren County Surrogate G. Thomas Moynihan Jr. ruled the original 1987 will valid.

A forgotten death

New York State Editor Michael Kilian writes about how the Karen Mason project came to be.

Kearney Mason would take possession of most of Karen Mason's belongings and property, including her share of their home in Hadley.

Lorena "Lucky" Rew, Karen's mother, would get her daughter's jewelry, including her white gold wedding band and her yellow gold diamond engagement ring, as well as another gold ring with a ruby and two diamond chips.

Her father, William Rew, received a single piece of Karen's property: the brand-new 1988 Oldsmobile she was in during those final frantic moments.

Eventually, Karen's family gave the car to her best friend, Pam Driscoll, who let it sit in her yard for a period of time before she ultimately decided to put it to use.

"It was hard," Pam said. "But it was Karen's."

Asked to reflect on his long-dead wife and what he thinks about when she comes to mind, Kearney, who spoke softly, in short answers, paused.

"I loved her," he said. He breathed in heavily, a stifled sob, then breathed out, "Very much."

Three decades after Karen's death, a public plea

It was 2020, more than nine years after reopening Karen's case, and State Police were looking for new leads.

By this point, they had interviewed and re-interviewed all the key players — Karen's ex-husband, her boyfriend, her friends and colleagues. They had hooked people to lie detectors, gathered old yearbooks to compare handwriting, and kicked around any number of theories.

That's when they decided to go public.

On Dec. 1, 2020, State Police publicized Karen's case for the first time as part of their "Cold Case Tuesday" program, in which they promote an unsolved case on their social media channels in hopes of generating some tips.

The circumstances surrounding Karen's death are "considered suspicious," the call-out read.

"The New York State Police are looking to speak with anyone who knew Karen at the time or may have had contact with her around the days preceding her death," the police wrote. "The public can call State Police at 1-800-448-3487."

The effort generated a round of media coverage, with Karen's face plastered on Albany television news broadcasts and on the front page of the local Post-Star newspaper.

And, more importantly, the effort generated tips, about a half-dozen of them, Lizzio said.

"Some of them are hearsay," he said. "Some of them are things that have manifested over time. But every tip is a good tip."

Lizzio's "every tip is a good tip" mantra is a major reason he decided to speak with reporters about Karen's case. Along with sitting for an interview, he took a reporter up to Hope — his hometown — to visit the home where Karen was found dead.

Have a tip?

If you have insight or information about the Karen Mason case, call New York State Police Troop G in Latham at 518-783-3211 or email crimetip@troopers.ny.gov.

His goal, he said, is that someone who knows something will read these stories. Maybe they will feel guilt. Maybe it will jog their memory. Maybe, just maybe, they will speak up.

"I think it’s solvable," he said.

He thinks he may know how Karen died. He has his suspicions about who else may have been involved.

One day, he hopes, he'll be able to prove it.

Do you know something that might help solve the Karen Mason case?

Reach out to us here

New Light: Karen Mason's Story

NY State Editor Michael Kilian writes about the Karen Mason Project

Timeline: Karen's life and investigation into her death

Meet the team

Reporting:Jon Campbell, Peter D. Kramer and Georgie Silvarole

Photography and video:Peter Carr, John Meore and Georgie Silvarole

Drone photography:Peter Carr and John Meore

Project management and storytelling editing:Kristen Cox Roby

Photo and video editing:Carrie Yale

Video production:John Meore

Audio editing:Matthew Leonard and Ryan Ross

Design, graphics and illustrations:Emily Nizzi

Social and promotion:Jackee Coe and Elizabeth Lombardi

Additional support:Kasia Abrams, Jay Cannon, Zachary Croce, Mark Ferdinand, Keith Kraska, Michael Kilian, Len LaCara, Annette Meade, Candace Mitchell, Carol Motsinger, Laura Nichols, Scott Norris, Sean Oates, Kyle Omphroy, Peter Pietrangelo, Doug Schneider, Jeffery Schwaner, Kyle Slagle, Phil Strum, Katie Sullivan Borrelli, Robert Warburton, Reid Williams, David Wilson and Stan Wilson

This article originally appeared on New York State Team: Why Karen Mason investigators believe fatal fire was deliberately lit