After a friend attacked, a young writer and his cigar-smoking landlady wonder what can be done

Tires on several cars were slashed in one neighborhood, a newspaper carrier was bitten by a dog on Grayson Avenue and the owners of five storage sheds in Waynesboro found them burgled.

The Staunton Leader published its weekday editions in the afternoon, and these items made the March 15, 1979, edition.

You can learn a lot about a community from its newspaper. The movie “The Great Train Robbery,” starring Sean Connery, was opening at the Visulite. An editorial cartoon captioned "The Truth Behind the Veil" criticized Iran's crackdown on women's rights. Ralph Sampson’s basketball team up the road in Harrisonburg was beating every high school squad in the state. A five-course meal at Kentucky Fried Chicken was $1.88.

Later in March there’d be a report in the paper of a local cross burning.

You also can learn a lot about a community from what its local newspaper doesn’t report. There would be no story about the violent rape of a Mary Baldwin College student in her dormitory; not in the March 15 edition or any other edition of The Leader for months.

When it came to American women’s rights, there was still much kept hidden behind the veil of 1970s culture, where silence seemed to be the mainstream response to violence against women. That included the college asking the cops to delay reporting the rape, according to a police spokesman’s statement months later.

In that silence, four more women were raped and several more assaulted.

*

Ray Robertson sat comfortably in his den while his mind wandered back to uncomfortable times.

“He wore a uniform,” the former commonwealth’s attorney for Staunton said in a 2019 interview about the 1970s rapist. He had a scar on his leg, and walked with a slight limp. He was a young Black man who wore a stocking mask and threatened his victims with a knife. In one rape, he’d made use of a ladder in the yard to climb to a second-floor window and slip in.

“And he apologized to his victims.” Robertson knew about the apologies, about the knife and the mask, from the victims of the criminal who became known as the stocking mask rapist.

He heard those details from one other person that year: a psychic who became involved in the case on the insistence of the third victim’s sister. A tall and striking woman from over the mountain in Ruckersville, she told them things that only the police and the rapist’s victims knew. And more.

About the scar on his leg, his slight limp. About how she was sure he lived across the street from a theater downtown. All those impressions turned out to be correct.

Including her directions to look for a handprint on the banister by the landing where the intruder steadied himself after dropping from the windowsill. It would be the only strong piece of physical evidence police would have when going to trial.

Forty years later, Robertson shakes his head about it. A psychic, sitting on a rape survivor’s bed, repeating in minutes what investigators had struggled to learn over the course of months, and then providing additional details that were not possible for someone to know.

“I’ve always been really skeptical about that stuff,” he said, leaning forward a little, then settling back in his armchair.

“But I gotta tell you, these are the facts of the case.”

*

Charles Culbertson had been writing occasional pieces for The Staunton Leader for a few years. His break had come when his landlady wrote to the newspaper notifying them that “there’s a young man in my house who writes all day long.”

The paper’s editor told her to send him the couple of hundred yards from her house on Church Street to The Leader offices on Central Avenue, and a freelancing career was born.

He wasn’t the only tenant that the widow on Church Street took in as a boarder, renting rooms in the old house that otherwise would have seemed empty. To the young and single “Charlie,” as she called him, Mrs. Audrey Higgs was family.

And, like family, he sometimes called her by her preferred name, “Sugar.”

He and Mrs. Higgs would discuss the serial rapist case many times in 1979. Culbertson would come downstairs and make his morning coffee and sit in a chair by the kitchen window. A few feet away, she’d be stationed in her normal place at the Formica table, wearing a loose-fitting floral print dress that made it easier for her to move around despite chronic arthritis.

They’d sit and converse for hours. “Smoke and talk, talk and smoke,” Culbertson remembered in a 2021 interview. “She wanted that rapist caught, and I think she would even have liked to capture him herself. She was fearless.”

Culbertson would have his chance to eventually write about the stocking mask rapist, but for now his writing about it was confined to his journal entries.

He knew the first victim, a Mary Baldwin student.

When the door of her dorm room opened, she thought it was her roommate, who'd just left for a night out. But it was a man with a stocking mask pulled down over his head. He'd forced her into the bathroom and pushed her against the sink, pressing a knife to her throat.

He asked if she liked making love as he blocked her way out. "Not with a knife, not a knife," she shouted.

"Shut up!" he told her.

Nobody heard her protests, or his repeated apologies as he locked her into the bathroom. But one student down the hall told police she saw her doorknob quietly turning around the same time the attack took place. Her door, unlike Culbertson's friend, was locked.

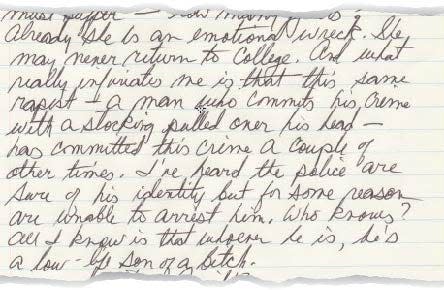

Pondering the recent death of a friend of his, he wrote in his journal in April 1979 how that person’s suffering was over. But his friend from Mary Baldwin? She "will suffer — how many years?” he wrote. “Already she is an emotional wreck. She may never return to college.

“And what really infuriates me is that this same rapist — who commits his crime with a stocking pulled over his head — has committed this crime a couple of other times.”

Culbertson hoped that “the low-life son of a bitch” was caught soon. It was not the last time he’d write in his journal as female friends he knew began to panic. It was not the last time someone in his own circle would be victimized.

*

The news was quiet as spring turned to summer, but the man who’d come to be known as the stocking mask rapist was active.

He broke into three downtown houses on Kalorama Street, North New Street and South Madison Street in a period of two weeks in late April and mid-May, stealing coins and jewelry, a stereo receiver and speaker.

He started out forcing locked doors open with a screwdriver, but learned as the weather warmed that if he cut open the window screens he often found the windows unlocked and even ajar.

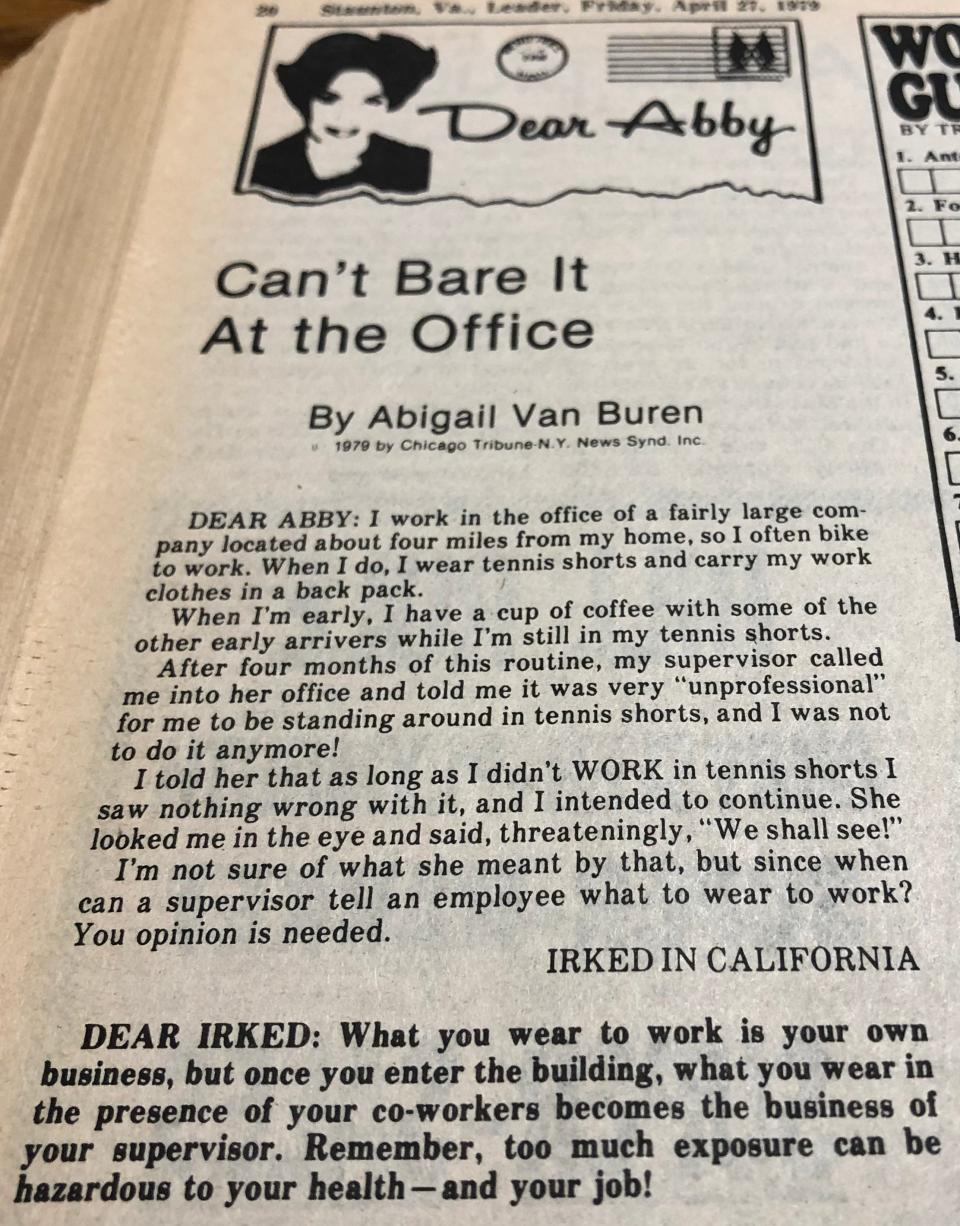

On the eve of the multiple house break-ins, Dear Abby was warning women readers of The Staunton Leader about showing up to work in shorts. Men’s responses were the fault of the women, according to the column: “Too much exposure,” Abby lectured, “can be hazardous to your health — and your job!”

Echoing the popular columnist, early conversations about the stocking mask rapist would also center on how women chose to appear in public, as if “commonsense tips” and lower hemlines would protect them from being attacked in their homes.

Women’s undergarments were stolen in another flurry of break-ins on May 24, May 29 and June 6. Several homes were entered in the span of a few hours.

In the midst of it, a woman fought off a man with a stocking mask entering her house on Sunday night, May 27, on West Frederick Street.

The next break-in would result in a second rape victim.

*

On a mild and cloudy Sunday night, June 3, in a neighborhood across the street from the city’s popular Gypsy Hill Park, a teenage girl was studying in her room.

Suddenly, she heard a sound in the house louder than the television she’d left on in the living room. A man opened her bedroom door wearing a stocking mask over his face and holding a knife.

He asked her if she smoked pot, if she had any money. Where was her mother at? She sensed he was nervous. He told her to take her underpants off and lay on the bed.

At 9:45 p.m., police received a call from the teen. The responding officer noted she was wearing a short pink night gown and was “hysterical” when he arrived. She was nevertheless able to describe her attacker, characterize his voice as deep but fast-talking and remember many of the things the rapist said to her. What school do you go to? How old are you? What is your name?

A week later, a Hardee’s employee named Pam told her new co-worker that a girl from her class had been raped.

It hadn’t been reported in the news but everyone in school was talking about it. The girls in her class were scared.

The co-worker, who went by the name Jimmy Robinson, listened carefully and became protective of her.

What school did she go to? he asked her.

Lee High.

Jimmy offered to walk her home when her shift was over so that she’d feel safe.

Nine days later, a reader of The Staunton Leader’s police blotter would have found the first published hint of the danger facing the city: “Staunton police are looking for a man suspected of a rape, attempted rape, and three ‘sexually motivated’ break-ins in the city since May 24."

Another month would pass before any news of the rapist on the loose would reach the front page.

In those weeks of silence, a woman would come home about 11 p.m. on the first night of July, walk upstairs and be assaulted in her own bed by a man whose features were distorted by a stocking mask.

Jeff Schwaner is a journalist at The News Leader in Staunton and a storytelling and watchdog coach in the USA TODAY Network-So. Contact him at jschwaner@newsleader.com.

NEXT UP IN 'THE STOCKING MASK'

“The police said we had to set traps ourselves. We had to put up NO TRESPASSING signs. We’d string up fishing line in the driveway” between their houses, “about, you know, knee-high. And then between the fence and the bench. And one morning we got up and the bench leg was pulled out, and we knew that somebody had been there.”

The two women used an intercom system shared between the houses so they could immediately talk to one another.

When the news reached the public that a serial rapist was breaking into houses, Debbie, a single woman living alone, had more than a prowler to worry about.

“As a woman, it was an unsettling feeling,” Brenda Canning said. “It really was, and the backyards are really dark.”

PART 1: Serial rapist stalks vulnerable city while Staunton police, women’s college stay silent

PART 3: Cops admit predator is at large. Staunton women told to use ‘can of hair spray’ for defense.

PART 4: ‘Everyone’s scared to walk outside their houses — or stay in them’

PART 6: ‘You got two innocent people in jail, and a rapist still out there’

PART 7: Women make demands. A psychic makes predictions. And a Virginia city holds its breath.

PART 8: Things go ‘round and round’: Two unlikely sources help police close in on Staunton predator

PART 9: After a year of dread and violence, a Staunton suspect confesses, but is there evidence?

This article originally appeared on Staunton News Leader: Despite no news on stocking mask rapist, city becomes aware of threat