A new frontier for river access is being carved out in the Midlands. Here’s what the future looks like

One day, you will be able to ride your bike from Columbia’s Olympia neighborhood all the way to the Lake Murray dam.

Raise your hand if you’ve heard that before.

For years, leaders across the Midlands have longed for better connectivity of the three rivers that bisect the center of the state. They’ve scrounged dollars and lobbied public opinion, and finally, the pieces seem to be dramatically falling into place – particularly on the Saluda River, which for a long time has been considered a hidden gem in the region.

Greenway projects are funded, planned and built – with more on the way. And now two new developments will bring the pocket even more action: An $80 million endeavor by the Riverbanks Zoo and Garden, which includes a riverfront restaurant on stilts, and a new pickleball complex just north of the zoo.

All these plans, not to mention a $2 billion overhaul of the infamous Malfunction Junction interstate tangle that’s a gateway to the zoo area, signal the next frontier of activity in the capital city is at long last shifting toward this river corridor.

Not everyone is thrilled with the new development, with fears that projects will make the river less wild. But others are cautiously optimistic about what more people seeing the Saluda will mean for attention on and affection for the three rivers as a whole.

The zoo’s big plans

To start, Columbia was only going to have a small children’s zoo, with the city’s famed Happy the Tiger as the centerpiece.

The Columbia Zoological Society, formed in the early 1960s, got 16 acres of land from the South Carolina Electric & Gas Company along the Columbia side of the Saluda River for its plans. They needed $300,000 to build their zoo, but after years of effort could only raise about $60,000, according to the history book “Riverbanks Zoo and Garden: Forty Wild Years.”

The plan was a flop – at first.

But around the same time, Midlands leaders wanted to change the image of Columbia’s riverbanks, which up to that point had been industrially abused or wholly undeveloped.

The Zoological Society’s 16 acres sat in the middle of a 500-acre tract leaders hoped to turn into a sprawling riverfront park. The land was leased by SCE&G (now Dominion Energy) for $1 per year for 99 years, and politicos began planning for the park.

It hit a wall again, and the park never happened. But those who wanted a zoo all along had 500 acres and newfound support to do something creative with the Saluda riverfront. And so in 1974, Riverbanks Zoo and Garden was born.

The river, though, was still hidden away.

“It wasn’t until I started in 2002 ... that I was getting familiar with the property and walked out onto the bridge and I’m like … where did this river come from?” Riverbanks’ current CEO Tommy Stringfellow recalled in a recent interview. “I remember saying to myself back then, ‘Wow… I guess that’s why we call it Riverbanks,’ but it was not developed at all.”

Now with $80 million on the table, Stringfellow hopes to “put the river in Riverbanks.”

The zoo has grown slowly and in piecemeal stages. It exists on both sides of the Saluda River, straddling the Richland-Lexington county line. It was created as a special purpose district by the state Legislature so that it would be governed by both counties in addition to a commission formed for the purpose of its oversight.

For that reason, getting money to expand the zoo has required making plans that benefit the jurisdictions on either side of the river. When the zoo needs money, it asks for municipal bonds, which have to be approved by both counties.

Over the years, the zoo has used those dollars to add new attractions and to expand across the river. In 1994, it used money from a bond to open the botanical garden on the Lexington County side of the river. In 2012, the zoo got $32 million to build a new main plaza, adding the sea lion exhibit that visitors see when they enter and other new features.

Stringfellow joined the zoo in 2002 as marketing director and took over as CEO in 2017.

For a while, it seemed there wasn’t an interest in creating better access to the three rivers that bisect the region. But the attitude started to change in the early 2000s, when the River Alliance began pitching plans to build a greenway system along the rivers.

Stringfellow had long felt that Riverbanks Zoo could be part of that effort. So in 2022, when it was time to ask for another bond, Stringfellow saw a chance with the river.

“Because they’re on both sides of the river, that was my opportunity to try to get the angle of buying both counties into this bond,” he said.

The bond request for the next zoo expansion was rejected in 2022, but the zoo returned to the counties in 2023 to ask again, and in December, the $80 million bond was approved. (Richland County taxpayers will carry $44.8 million of the bond, and Lexington County will carry $35.2 million.)

That $80 million will fund a project, named “Bridge to the Wild,” that will see the Saluda riverbank developed like never before. The botanical garden side of the zoo will add a primate garden, which visitors will be able to view from various angles along the hillside, as switchbacks take visitors up and down the incline.

An aerial gondola will also take visitors back and forth across the Saluda.

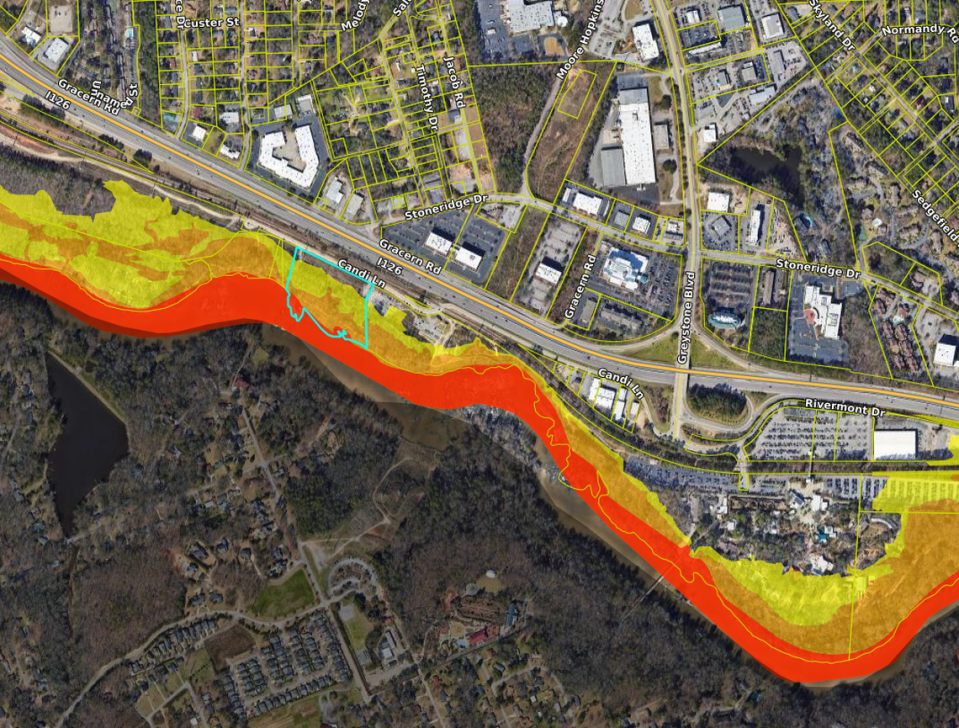

And the zoo will build a boardwalk and restaurant on stilts overlooking the river, using the stilts to overcome the floodplain concerns that kept the zoo from developing close to the riverbank for so long.

But there’s a reason the zoo hasn’t tried this sort of development before. It will be expensive and somewhat of a risk, Stringfellow said. New water and sewer lines will need to be built, and there is a chance that they will hit granite as they start to build.

“We’re kind of taking a gamble that we won’t hit too much rock,” Stringfellow said, but he added that there are contingencies if that happens.

Stringfellow hopes that there may also be a way to connect the zoo’s new restaurant to the Saluda River Greenway.

Connectivity, baby

As the zoo’s big riverfront dreams are being built, plans are moving forward elsewhere to create more access to the Saluda portion of the three rivers.

“A lot of people discover the river because they go to the zoo,” said Mike Dawson, CEO of the River Alliance, which has spearheaded efforts to build the Three Rivers Greenway.

For more than a decade now, Dawson has been dreaming of connecting the Lake Murray Dam to the Columbia Canal and beyond, to Granby Park in the Olympia neighborhood.

And pieces are falling into place to create more connectivity across the rivers than ever before.

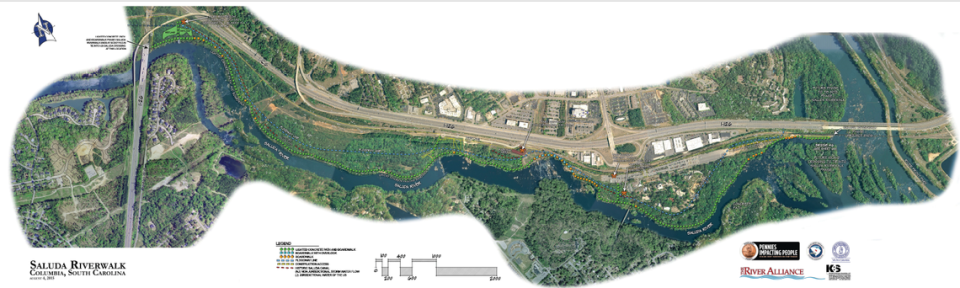

The Irmo-Chapin Recreation Commission is working to finish the Lower Saluda Greenway running northwest of the zoo and downtown Columbia, from Lake Murray. It will connect the existing Saluda Riverwalk, which currently runs alongside the zoo and ends at Interstate 26, to the Lake Murray Dam.

Dominion Energy has also leased another 200 acres to local governments along the Saluda that will allow for more trails and bike paths once work on Malfunction Junction is complete.

The Saluda Riverwalk is already connected to Boyd Island, which sits at the confluence of the Saluda and Broad rivers heading toward downtown Columbia, where those two rivers come together to form the Congaree River. Next, the Boyd Foundation is helping to build a bridge from Boyd Island to the Columbia Canal.

Meanwhile, West Columbia is discussing building a pedestrian bridge to connect from its side of the Saluda next to the zoo’s botanical garden, across the river to the Saluda Riverwalk near Candi Lane, which serendipitously would also help connect walkers to the eventual pickleball complex planned just northwest of the zoo.

That pickleball complex, PickleGarden on the River, will have the Saluda Riverwalk going directly through its property.

“The greenway itself, as we get it connected, becomes more than the sum of its parts, and that’s a good thing,” Dawson said. “We’re going to have a lot of access to nature that is promotable.”

Farther south, the city of Columbia is working on plans that would help achieve Dawson’s goal of connecting the greenway all the way down to Granby Park, where a short greenway already exists.

The city has $9 million from the state budget and another roughly $8 million from Richland County’s transportation penny sales tax program to connect Williams Street between the Blossom Street bridge and Senate Street, just below the Gervais Street bridge.

That project was initially part of a $50 million plan laid out in the 2012 penny tax program with the specific goal of creating more access to the Congaree River.

Columbia City Councilman Will Brennan said that project may break ground as early as the end of this summer.

Brennan agreed that for years, there was a desire to better promote the rivers, but not the collaboration.

“You’ve got a regional approach now,” he said of all the work along the three rivers.

Brennan added that while much of the area along the Congaree River where the city’s project sits isn’t suitable for commercial development because of the floodplains, there will be space along the new stretch of Williams Street for residential projects. He hopes to see hotels and apartments on the horizon.

Dreams of a riverfront park have also been floating for 15 years, and a land donation by the Guignard family who owns the bulk of property between the Gervais and Blossom street bridges show those goals are moving ahead as well.

Development and conservation

As development picks up along the rivers, those who love the spaces for their natural beauty and solitude have raised alarms that not all of these projects are suited for the river.

“It’s a very complicated balancing act,” said Congaree Riverkeeper Bill Stangler, who advocates for conservation and water quality protections around the Midlands. “We certainly want to see more people get out and enjoy the rivers. … But any kind of development that’s going to put more infrastructure down there and more people, but also more hardscape and things like that has to be done really delicately to preserve the river ecosystem.”

The announcement of PickleGarden on the River, which will be located on 5 acres near the zoo at 680 Candi Lane, incensed many residents. One person started a petition against the project, which received more than 5,000 online signatures.

Abbott “Tre” Bray, who sits on the Lexington 2 school board, is one of the owners of the pickleball project. Bray called the Candi Lane location the “be all, end all,” because it’s one of the only parcels near the Saluda River primed for development.

“We made the determination that if we can’t get this property, we’re just not going to do it,” Bray said of developing on the river, given that he said the goal of the project is get more people outside and enjoying natural resources in the Midlands. He didn’t anticipate the degree of online pushback the project received, but he agreed that renderings shared in the announcement made the project appear to be much closer to the river than it will actually be.

But he added that some people think the river is their private getaway, and he wants this project to help get more people to see the resources that already exist on the river.

Bray also said he’s gotten offers from other developers who have told him if he and his partners decide not to move forward with the PickleGarden project, they would buy the property for much more than Bray and his partners purchased it for. He said they turned down those offers and are moving ahead with the pickleball project.

He said they plan to be conscientious about the river and the ecosystem they will be developing around.

Stangler has met with Bray and his partners about the pickleball complex and shared some concerns, including about how much of a buffer they will keep between development and the river. Stangler said time will tell if those concerns are heeded.

Stangler said he and other conservationists also have questions about how the zoo’s development will move forward and will be watching that work closely.

For Bray’s part, he said he hopes to maintain a 100-foot buffer between the pickleball site and the river, which is in line with what the state’s Department of Natural Resources advocates for and twice as much as the city of Columbia requires.

“The science says 300 feet is ideal for water quality; 100 feet is just the bare minimum (recommendation),” Stangler added.

“I’d like to see (developers) required to do more, but I also know that we’ve had some success working with folks … where we explain to them, ‘Hey, here’s the value, here’s what you can do to make this better,’” Stangler said, but he acknowledged that for many, the decision of how much effort is put into conservation is an economic one.

But where regulations may be lax in the eyes of conservationists, public opinion may be stronger — the outcry over the PickleGarden project being one example.

And as public support grows for the rivers, and for keeping them as natural as possible, advocates say they are optimistic about finally leveraging the natural resources the community has overlooked for so long.

“What’s really fun for us is to see people using those greenways every day,” Dawson said. “Once the river becomes part of someone’s life and their stories, then we really arrive.”