FSCJ professor: In polarizing times, the U.S. should revisit Madison’s ‘middle path’

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

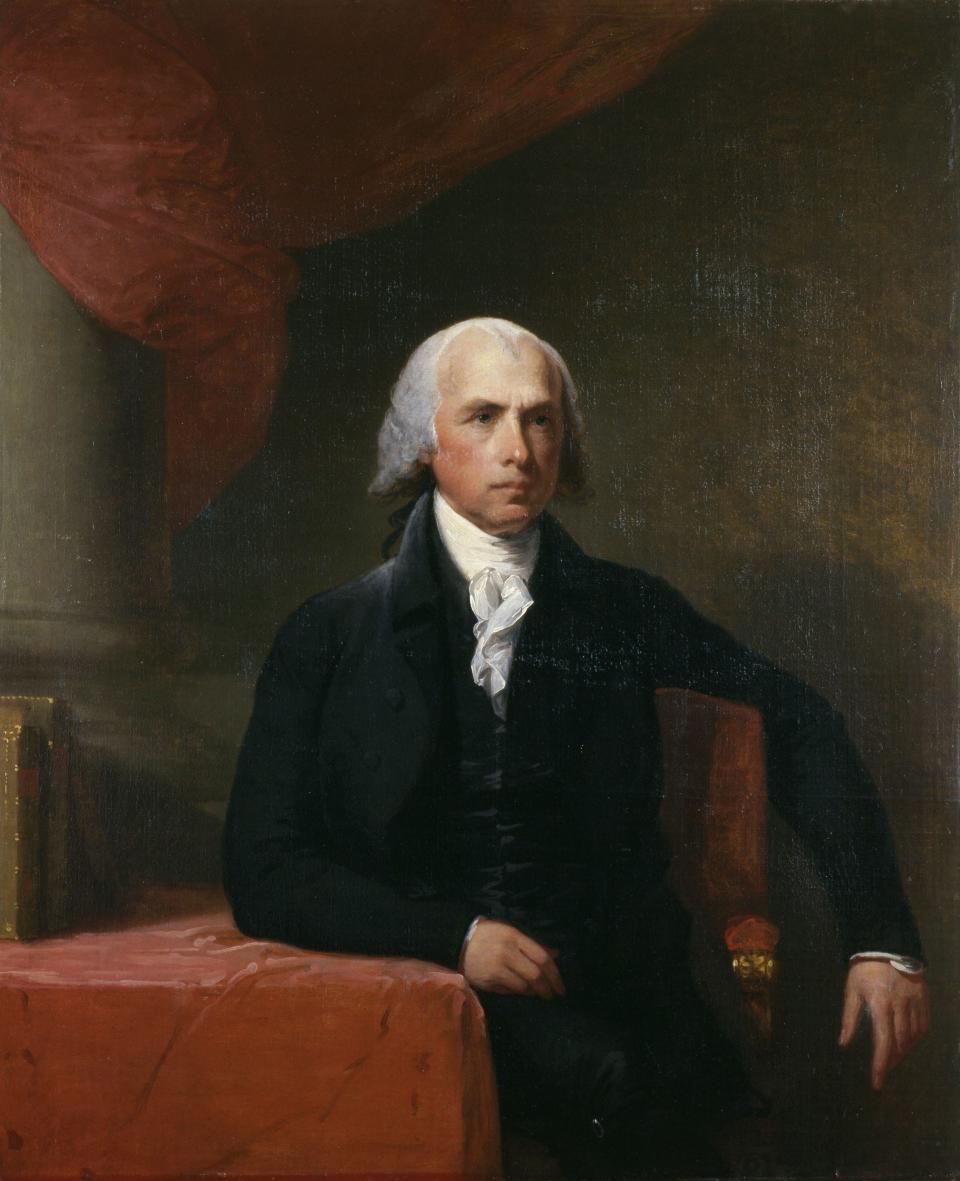

James Madison, the architect of the U.S. Constitution, played a major role in its ratification process. He articulated his ideas in The Federalist Papers, in which he tried to address the concerns of the Anti-Federalists on contentious issues such as division of powers between the newly formed nation and the states.

Madison’s wisdom was reflected in his reconciliatory approach and moderation of extreme positions through debate and dialogue. That this Madisonian wisdom is lacking in democracies of our times is perhaps an understatement.

As reflected in the Articles of Confederation, the Founding Fathers — after independence from the colonial yoke — preferred a weak national government. But in its brief existence, the confederation proved a toothless tiger. For example, it lacked the power of taxation and the power to check armed rebellion.

Our forefathers decided to address this weakness and convened in Philadelphia to draft the Constitution. The process of ratification was not easy. It was Madison’s willingness to accommodate the demands of the opposition — such as drafting the Bill of Rights to address the concerns of Anti-Federalists, thus exploring a middle path through debate and dialogue — that played a major role in the ratification of the Constitution.

Madison was influenced by Greek philosophy, as well as the Age of Enlightenment. Federalist Paper 49 used the terms “enlightened reason” and “nation of philosophers,” reflecting the influence of Plato. Federalist Paper 51 made a pertinent observation on human nature and argued for rule of law: “If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary.”

Letters: Tax prep volunteers needed in Jacksonville to provide vital free services for 2023 filing season

It added, “In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: You must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.” Thus, one of the challenges before Madison was how to checkmate human passion and selfishness, letting it be governed by higher reason that puts the country before narrow individual interests. Madison argued that when people are virtuous, disciplined and guided by “enlightened reason,” strict rules and regulations are not necessary.

But the pragmatist in him realized that as such an ideal scenario is not possible, it is necessary to establish rule of law. But Madison’s pragmatism was suffused with optimism that Americans would carry on and strengthen the democratic republican vision that guided the founding of the Constitution.

That was one reason why the founders did not include everything in the Constitution and produced a small, but powerful, document (unlike constitutions in some other countries, which run into hundreds of pages). As articulated by historian David McCullough, the Founding Fathers — neither perfect themselves, nor creators of a perfect democratic system — were guided by the vision that the democratic republic they were founding would evolve with passing decades, as it is guided by “enlightened reason.”

Madison spent considerable energy in addressing the Anti-Federalist concern that a strong nation would usurp powers of the states and result in tyranny. While elaborating on it in Federalist Paper 39, he adopted a middle path. He wrote, “The proposed Constitution, therefore, is, in strictness, neither a national nor a federal Constitution, but a composition of both.

“In its foundation it is federal, not national; in the sources from which the ordinary powers of the government are drawn, it is partly federal and partly national; in the operation of these powers, it is national, not federal; in the extent of them, again, it is federal, not national; and, finally, in the authoritative mode of introducing amendments, it is neither wholly federal nor wholly national.”

Here Madison developed the concept of shared sovereignty, implying neither the national government nor the state governments are sovereign (which traditionally places sovereignty — the legitimate right to rule — in one center of power). Instead, they share power depending on context and circumstances.

More from Prof. Mahapatra: The need for friendship, peace and education in a changing world

For Madison, the foundation of the nation is federal, implying that the states laid the foundation of the nation, since the original 13 colonies preceded its creation. Thus, the powers of the government were both federal and national — in this context, one could think of members of House of Representatives being directly elected by the people, while members of the Senate are elected by state legislatures (though they were elected directly by the people after passage of the 17th Amendment in 1913).

Another example he provided was the constitutional amendment process in which both the national government and states played roles. For Madison, the American democratic political system embodied a combination of national sovereignty and state sovereignty in reciprocal, harmonious ways, keeping in view the best interests of the people, the states and the nation.

This reconciliatory vision led the evolution of the U.S. as one of the most powerful and pluralistic democracies in the world, despite myriad challenges in the past two centuries. Madison played a role in this process, and as a founder and leader of the nation, exemplified this vision in his public life.

The Madisonian path of dialogue and collaboration, as well as his vision of a democratic republican government led by leaders of “enlightened reason,” must be revisited to address our contemporary crises.

Debidatta A. Mahapatra, Ph.D., professor of political science, Florida State College at Jacksonville

This guest column is the opinion of the author and does not necessarily represent the views of the Times-Union. We welcome a diversity of opinions.

This article originally appeared on Florida Times-Union: James Madison was willing to meet opposition halfway; why can't we?