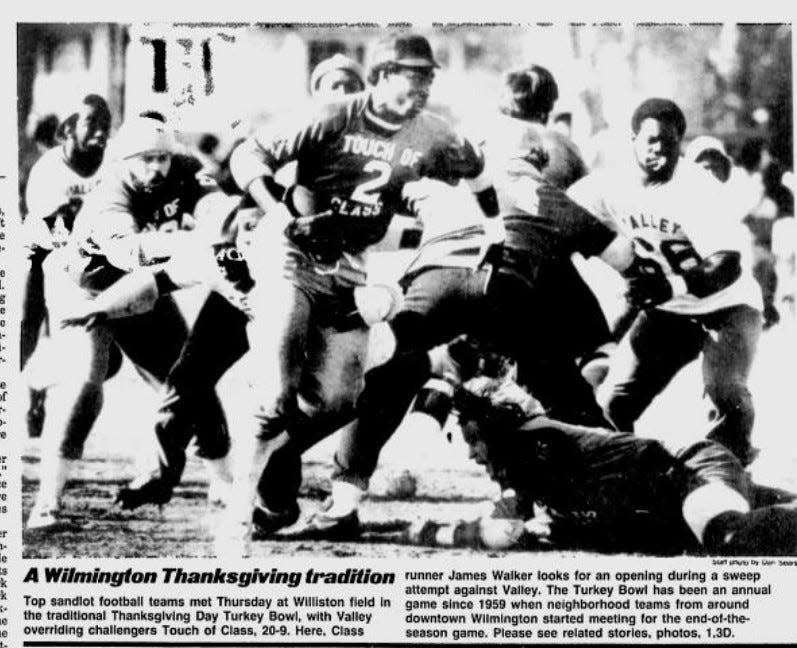

Full contact, no pads: Wilmington's fabled Turkey Bowl is gone but not forgotten

It's been years since the Turkey Bowl was held in downtown Wilmington. But every time Thanksgiving rolls around, the once-annual football game and social gathering becomes a topic of conversation among longtime members of Wilmington's Black community.

Notorious for players who competed in the full-contact game without the benefit of helmets or pads, the Turkey Bowl was more than just a football game. Held every Thanksgiving for decades until the mid-2010s, it was an event that united the community, drawing both Wilmington residents and former locals who were back in town for the holiday to visit family.

"Everybody went. You'd see people you hadn't seen in years," said Natalie Williams, working her shift recently at the 1 Stop Shop Grocery at 13th and Ann streets. "It was a real popular thing. I'd try to hurry up and cook my (Thanksgiving) dinner so I could go out there and socialize."

More: Wilmington historyFamous 'Williston Buns' live on at downtown Wilmington corner store

The game was played on the field next to the former Williston High School, now a middle school, where Williams graduated in 1967 when it was still a segregated, Blacks-only school.

"You couldn't park nowhere near the field," said 1 Stop Shop owner Will Bordeaux, who attended the game most years and played in it when he was younger. "People would actually buy new clothes just to go to the Turkey Bowl. It was as big as the Azalea Festival for us."

Wilmington's Fred Taylor said he first played in the game in 1967 as a 17-year-old on a team called The Unifics.

"It was packed," he said. "Everybody and their mama was out there."

The atmosphere was jubilant and spectators numbered in the hundreds, if not well over a thousand, but the game itself was not for the faint of heart.

"It was interesting because the football players didn't wear any protection," said historian, author and radio host Larry Reni Thomas, who grew up in Wilmington but now lives in Durham. "No shoulder pads, helmets, etc. It was insane."

Not surprisingly, injuries were common.

“A guy might get a broke arm or leg, but nothing serious,” Mike Jacobs, who played in several Turkey Bowls and later helped organize them, told the StarNews in 2005.

Although the game became a one-off in its later years, in its early days the Turkey Bowl served as the championship game of a sandlot, no-pads football league. Teams from Wilmington public housing projects including Jervay, Creekwood and Hillcrest would all compete, as would teams from Leland in Brunswick County and Scotts Hill near the New Hanover/Pender County line.

The teams that made it to the Turkey Bowl championship − the prize for winning was essentially bragging rights and a nice trophy − "Those were the big boys," Taylor said.

In 2005, Jacobs told the StarNews that at least one former pro athlete, 6-foot-6, 290-pound defensive end Clyde Simmons, played in the Turkey Bowl before going on to star for Western Carolina University and the NFL's Philadelphia Eagles.

Local lore, and published reports in both the StarNews and the Wilmington Journal, say the Turkey Bowl grew out of an informal neighborhood game called the Oyster Bowl, which began in the 1930s (some sources say 1931) and was originally played before Thanksgiving. Later, area clubs and civic groups got involved. By 1958, according to a story in the old Morning Star, a predecessor of the StarNews, teams were largely populated by residents of Wilmington's public housing projects.

In 2002, William Murphy, who played in the Turkey Bowl and started helping to referee and organize them in the 1970s, told the StarNews that the game's popularity really took off during the 1960s. Bordeaux, Williams and Taylor all say they remember the game being preceded by a parade and by a Turkey Bowl pageant, and followed up by a dance. Vendors would sell food and other items before, during and after the game, and Bordeaux said the Turkey Bowl inspired community games in other towns, including Jacksonville.

A StarNews story from 2002 by reporter Millard Ives said the game "is known for its full-body contact, no helmets or pads, and a multitude of attitude from players with nicknames such as Maniac, Chaos and Assassin. (It's) considered the Super Bowl of the 'hood' and is enveloped by hip-hop and R&B music blaring out of speakers from cars surrounding the field."

Murphy died in 2009 at the age of 74 after many years of directing the Martin Luther King Community Center. That year, the game was renamed the William E. Murphy Turkey Bowl to honor him. His picture still hangs in Bordeaux's 1 Stop Shop, and Bordeaux gives Murphy credit with not only keeping the Turkey Bowl going for decades, but also with being one of a half dozen people who helped keep Wilmington's Black community unified through the 1970s and into the '80s and '90s.

"It's hard to talk about anything community-wise without talking about him," Bordeaux said. "He was the babysitter for the whole Southside" during his tenure leading the MLK Center. The center started as "basically just a shack with one pool table and a pingpong table," Taylor said, and evolved under Murphy's leadership into the community resource center it is today.

By the early 2000s, participation in the Turkey Bowl had begun to dwindle. The community still came out for the game, but Murphy told the StarNews in 2002 that the formation of a local semipro team pulled lots of players from the local sandlot league, which collapsed.

Even so, the Turkey Bowl kept going for years, often with teams being hastily assembled in the days before Thanksgiving.

"It started dwindling," said Hollis Briggs, who helped run the game under the auspices of the MLK Center for a few years last decade. "There were more older people, and no young bloods to come in and take over."

Bordeaux agreed that "we couldn't get the guys to hardly play no more." In 2008, a four-team women's flag football league was started to try to continue the tradition. It lasted for a few years. A men's flag football Turkey Bowl proved unpopular, Bordeaux said, adding that the last Turkey Bowl was an informal community kickball game sometime in the middle of last decade. Murphy's daughter, Portia, tried to keep the game going after her father's death but was unsuccessful, Bordeaux said.

"Things change," Williams said. But, for the community, the Turkey Bowl "meant a great deal. Everybody looked forward to it."

"I tell people, 'Those were the fun times,'" she said. "Now it's, 'Somebody got killed. Somebody got shot.' Now is more of a scary time for me."

Bordeaux and Taylor agreed that the game united the Black community in a way that doesn't exist anymore, at least not in the same way.

Asked if the game might ever come back, Taylor said, "I don't think so. ... Now, we ain't got nowhere to go on Thanksgiving."

Contact John Staton at 910-343-2343 or John.Staton@StarNewsOnline.com.

This article originally appeared on Wilmington StarNews: Wilmington's Turkey Bowl football game helped unite Black community