‘The full picture.’ Descendant of the enslaved at Gamble Plantation pushes for change

When Chandra Bivens Carty visits Gamble Plantation, she pictures what it might have looked like in the mid-1800s.

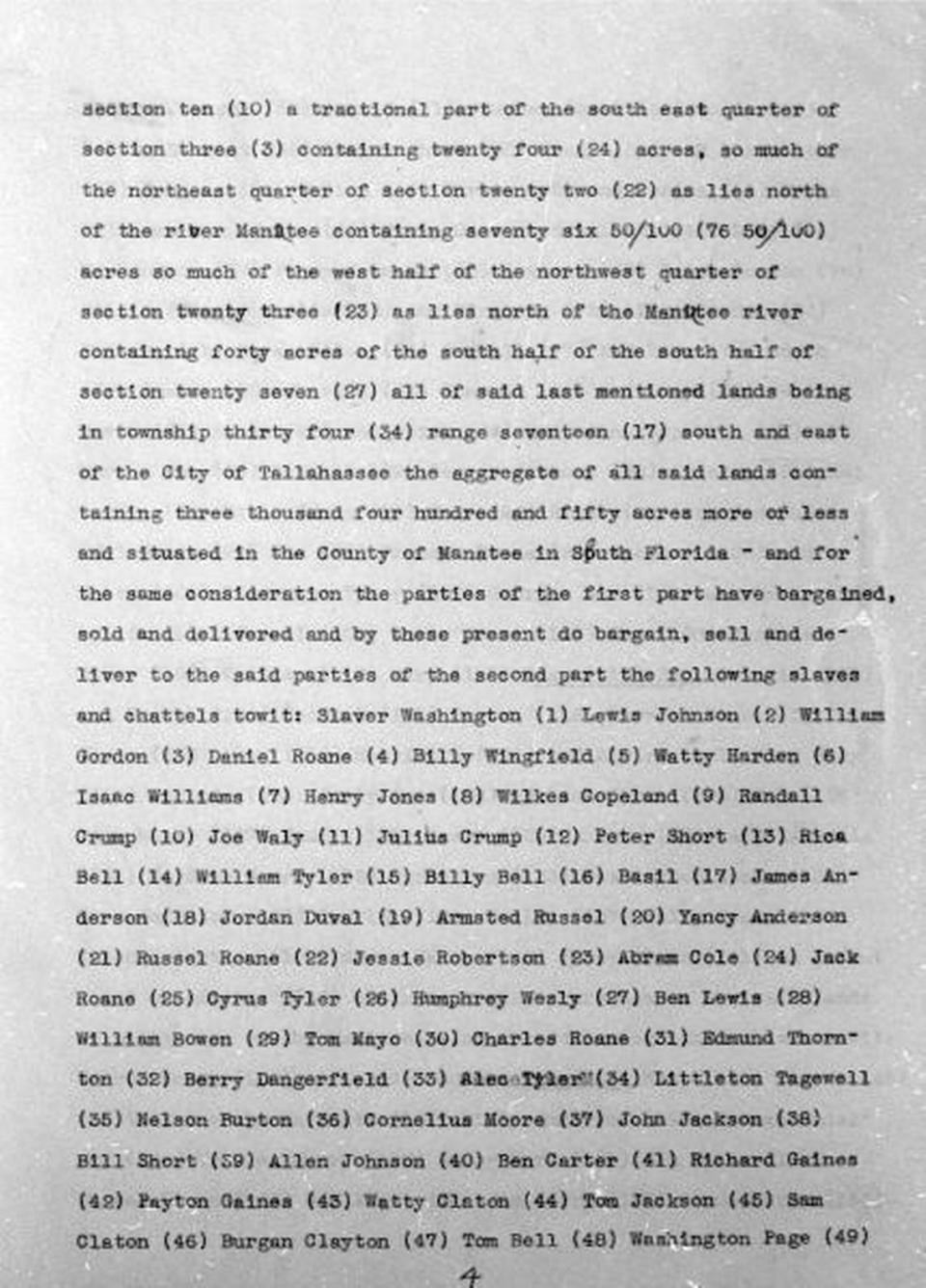

That’s when her great-great-grandfather was one of more than 150 people enslaved at the former sugar plantation in Ellenton, just north of the Manatee River.

Carty wonders: Did he clear the land? Did he toil in the sugar works?

Many details seem lost to history. There are no photos from the time period — only dates, a few historical records, a slave number and a name: Nelson Burton.

“If only the trees could talk,” she said. “I’m quite sure Nelson Burton walked these grounds many a day.”

In 1972, Carty was in the top 10% of Southeast High School’s class. They visited the plantation, now a state park, to take yearbook snapshots.

At the time, she had no idea about her family’s ties to the land. Or that over 100 years ago, her relative may have helped build the mansion she was standing in.

Since then, Carty moved away from Bradenton. She got a degree in food science from the University of Florida, a master’s of medical science from Emory University and became a dietitian and nutritionist in Georgia.

It wouldn’t be until years later that a cousin’s work to map out the family history piqued Carty’s interest in the past.

“I decided to find out more information,” Carty said.

Shaping Gamble’s future

Now Carty, 68, is on a mission to bring her family’s ties to Gamble Plantation to light.

As a state park, the plantation has drawn criticism for the lack of information about enslaved people who once lived there.

Instead, the park’s focus has been on the planter lifestyle and the mansion’s role in the Confederacy.

“Right now their whole focus is the Confederacy. They don’t know any other way,” Carty said.

The plantation provided supplies to the Confederacy during the Civil War. It is also thought to have been a stop for Judah P. Benjamin, the Confederate secretary of state, as he fled the U.S. when it became clear that the South’s defeat was imminent.

Previous attempts to expand the park’s narrative to include more information about slavery met backlash from the United Daughters of the Confederacy. The heritage organization has had close ties with the Florida Parks Service in determining the fate of the park since its members bought and donated the land to the state in 1925.

Visiting the plantation on a hot July day nearly 100 years later, Carty said she feels like not much has changed.

“Things here do move slowly. But it moves. You have to begin conversations,” she said.

Carty recently joined the Gamble Plantation Preservation Alliance, the nonprofit volunteer group that helps set priorities for the park.

She’s hoping that, backed by her family history, she can help fill in some missing pieces of the narrative at Gamble.

“I’m not trying to erase anything,” Carty said. “I just want to add to what’s there.”

“I hope they can take away the full picture,” Carty said of the thousands of people who visit the site each year.

Carty’s bid to tell more history of enslaved African Americans comes at a time when the subject has become highly politicized. Gov. Ron DeSantis and top Republicans have made controversial moves to limit how the history of slavery is taught in Florida schools.

“This situation could stress a lot of people out,” Carty said. “But I think this is the right time.”

With past experience writing research grants, she believes she can help secure funds for additional signage and other updates before the park’s next management plan is approved in 2025.

If that fails, Carty said she is willing to pay for a memorial to the enslaved out of her own pocket.

“We know where all the family is buried except Nelson,” Carty said. “So having a memorial, to me, is bringing closure to his life.”

It’s a history that was almost lost to the Bivens family.

And, according to Carty, we can’t learn from history that is lost — or celebrate how far we’ve come. On that note, there is a more recent piece of family history that Carty likes to highlight.

She points out that despite his legal brilliance, Judah P. Benjamin failed to graduate from Yale. Carty’s daughter completed her postdoctoral fellowship at the university.

“So who’s to say enslaved people have to be stymied by their situation?“ Carty said.

“When someone claims that the slaves didn’t know what to do after slavery — I’m challenging that one,” she added.

Her family’s legacy in Manatee County speaks for itself.

Tracing descendant’s past

Genealogy research and documents on file at the Manatee County Historical Records Library draw an impressive line through the decades, from Burton to Carty.

FOUR GENERATIONS AGO: Nelson Burton and his wife Mariah Washington, another ex-slave, were married in 1872. Research suggests that Mariah may have also been enslaved at the plantation.

The couple was the head of a family that would come to have a significant impact on Manatee County over several generations — especially when it came to opening up education opportunities for Black residents.

Mariah Washington had four children when she married Nelson Burton. They included Melissa Harrison, Carty’s great-grandmother.

THREE GENERATIONS AGO: In 1876, Harrison married Juneous Adams. Adams was an ex-slave who came to Manatee County to pick citrus fruit, according to Carty.

Harrison was at one point a matron at a school outside of Ocala, and she and Adams ensured all of their children received an education, according to genealogy research.

In Manatee County, Adams helped found two churches that doubled as schools for Black children who did not yet have their own public schools in the segregated Jim Crow-era South.

TWO GENERATIONS AGO: Juneous and Melissa’s children included Bessie Adams, born in 1888. Bessie was very active in the community. Her efforts included helping to found the East Bradenton Woman’s Club, which successfully advocated for a longer local school year.

Bessie married Cleveland Williams, known to Carty as “Grandaddy Cleveland.”

At one point, Cleveland lost his job for confiding in his boss that he was educating his children, family memoirs say.

But he found work up north in another county and secured the necessary funds to put his daughter through school.

ONE GENERATION AGO: Carty’s mother, Naomi Williams, was born to Bessie and Cleveland in 1923. She would marry Carty’s father, Joseph Bivens, in 1948. Both were career educators in the Bradenton area.

Naomi taught at Ballard Elementary School, according to Carty, and Joseph was the principal at Bradenton Elementary, First Street Elementary and Lincoln High School.

Bivens was the final principal to serve Lincoln High before it was integrated and converted into a middle school.

Scholarship fund honors parents

Though Carty has moved from Manatee County, her family’s legacy of encouraging education lives on through a scholarship fund.

The Joseph T. and Naomi W. Bivens Scholarship Fund, started in partnership with Manatee County Community Foundation, offers an annual boost for one minority student from Manatee County who is heading to college.